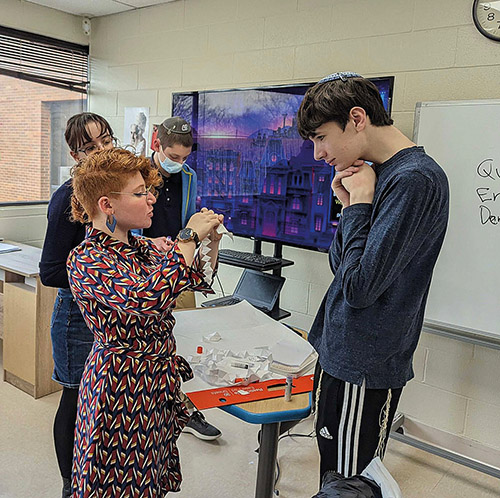

This semester, former Idea School student Emma Hasson, who left The Idea School after 10th grade to attend college, has since returned with a degree in math education in order to facilitate math experiences at the school that are engaging and enjoyable. Hasson, who spent a semester studying abroad in Budapest, Hungary, explored different approaches to math teaching and is moving to San Diego this summer for an internship in which she’ll be writing math curriculum that focuses on student discovery of mathematical principles.

Hasson shared, “Through the math club and other programming it is my hope to build a culture of intrigue and excitement around math. Throughout my studies I’ve always found math to be a beautiful and expressive and joyful pursuit, but what I’ve learned from my research is how important it is to share that perspective with others, and how simultaneously simple and complex it can be to break the cycle of anxiety around math.”

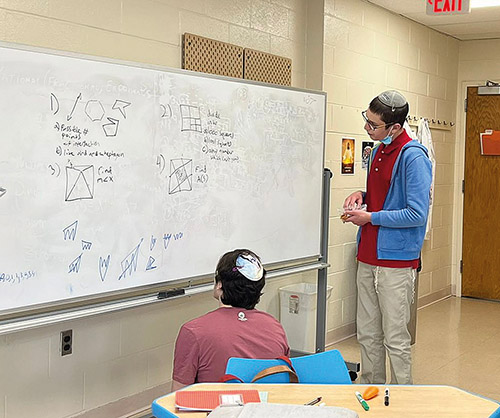

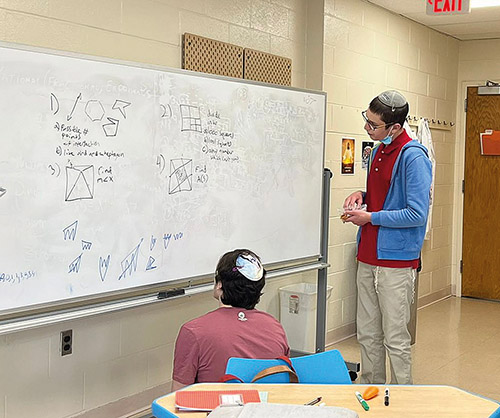

In addition to other responsibilities at the school, Hasson leads a math club each Tuesday. During one meeting, students learned how to make hexaflexagons—flexagons are flat models usually made by folding strips of paper that can be flexed or folded to reveal faces in addition to the two that were originally on the back and front. A hexaflexagon is a flexagon with six sides. After making the hexaflexagons out of paper, students then colored them in with a variety of mathematical patterns. Another meeting had students engaged in inquiry around geometry puzzles, starting with a problem and building on it by asking questions. This type of discovery-based math learning is a method Hasson learned in Hungary.

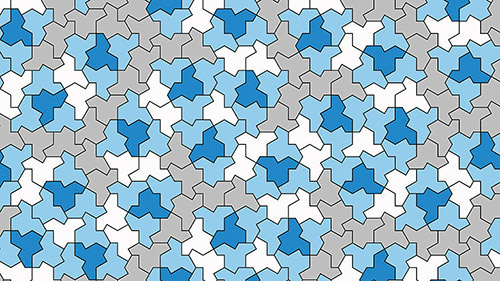

Recently the students had a discussion about math current events, specifically the discovery of an aperiodic monotile, a single tessellating shape that does not tessellate in a repeating pattern no matter how you put it together. It’s called an einstein monotile, which is a pun: ein is one and stein is stone. Mathematicians have been searching for the aperiodic monotile or something like it for ages, not sure it even existed.

Hasson added, “I think math is often seen as a rigid and unchanging subject where there is only ever one right answer, but more and more math is created every day by people who dare to consider the ‘wrong answers.’ Ultimately my goal is to have my students engage with math in a deep and rigorous but also lighthearted and joyful way.”