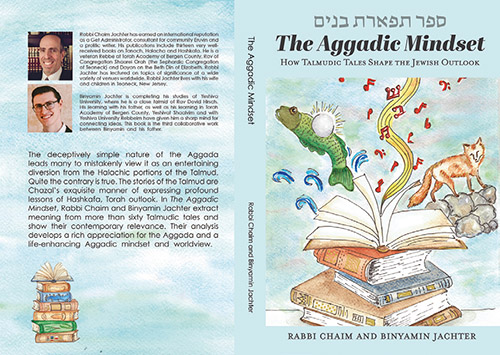

Reviewing: “The Aggadic Mindset: How Talmudic Tales Shape the Jewish Outlook,” by Rabbi Chaim and Binyamin Jachter. Kol Torah Publications, 2022. 320 pages. ISBN: 97988416449519.

Rabbi Chaim Jachter, with his son Binyamin, is ready to reveal one last fascinating project he undertook during the lockdown. While there were likely no more productive families in Teaneck during this time, I am told this is the last of four impressive books on which they collaborated during the pandemic. Remember that Rabbi Jachter is one of our newspaper’s valued weekly columnists, not missing a week in print since 2014! This sefer, with cover art for the second time provided by the talented Miriam Kaminetzky, was published in time to commemorate Binyamin’s wedding to Raizy Neuman this past Tuesday. Mazel tov!

While Rabbi Jachter, frequently with Binyamin as either a primary editor or a co-author (as in this case), wrote two seforim on specific books of Tanach (most recently “Opportunity in Exile: An In-Depth Exploration of Sefer Daniel,” 2022; and “Megillat Ruth: From Chaos to Kingship,” 2022) or halachic topics (“The Power of Shabbos,” 2022), this “fourth of four” of the lockdown books is a little different. It deals with the tales or stories from Chazal (our sages) which are less obvious, less easy to connect to halacha, and much more mysterious. Sometimes they sound downright wacky.

The Aggadah are the folklore-type tales that are peppered throughout the Gemara. They are tales told by or credited to the various rishonim who speak throughout the text, often Rabbi Yehuda (HaNasi), Rabbi Akiva, Rabbi Shimon (Rashbi), Rabban Gamliel, Rabbi Eliezer, Rabbi Yochanan, Rabbi Hillel, Rabbi Elazar ben Azaria and many others. These stories often lack context and sound entertainingly out-of-date to our modern ears, but even when we don’t understand them immediately, they carry the weight of thousands of years of history. They are also sometimes not simple to connect to the text they accompany. Often a masechta like Eruvin or Yom Kippur is honored with a tale that has no obvious tie to the creation of an eruv or the day of atonement.

While Rabbi Jachter writes in the introduction that it is tempting to see Aggadic text as an “entertaining diversion” from the serious matters of halacha, he warns that the reader would be wrong to assume that. “The Aggadic portions of the Germara are as integral to its message as the narrative portions of the Chumash. These sections impart lessons in a language that depicts an idea in a manner that halacha does not capture.” A primary example of this, he adds, is “Rabbi Akiva’s image of a raucous river that rests on Shabbat (Sanhedrin 65b) that perfectly captures the spirit of Shabbat.”

While many of the more well-known Aggadic stories make an appearance in the book, such as the fish with the priceless pearl in its stomach, the image of the fox and its association with the rebuilding of the Beit HaMikdash, and the healing powers of music and Torah study, many lesser-known stories, even some with significant context provided, are present as well.

In their construction of this sefer, Rabbi and Binyamin Jachter take the opportunity to look at Aggadic texts through the eyes of Shabbat and the annual cycle of the Yom Tovim, and share lessons gleaned from the Aggadah that are relevant to those times of year. In later chapters, they also relay Aggadic stories and lessons relating to topics such as marriage, debates, conversion, the practice of medicine, the halachic process, spirituality and character development.

The Jachters also take the opportunity to present Aggadic tales as a glimpse into Chayai Olam (eternity), and show how the various rishonim, particularly Rabbi Shimon, also known as Rashbi, who shared an array of thoughts on how this world corresponds to the next. “The Yerushalmi records: ‘Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai says, ‘Had I been present at Mount Sinai at the time the Torah was given to Israel, I would have asked God to create for man two mouths—one to engage [exclusively] in Torah and one to take care of all of a person’s other needs. [Shabbat 1:2]. Rashbi did not [initially] see a blend of this world and the next, and therefore dreamed of completely bifurcating eternal and temporal needs.’”

They then relay this story: “Rashbi was transformed by the sight of an elderly person on the cusp of this world and the next, near the crossover of the exit of Friday into Shabbat. The man was elevating the mundane myrtle branches to correspond to pesukim of the Torah. Rashbi rightly recognizes that Hashem fused these three points of advancing the worldly to the other-worldly to teach him to see another way. Tending to everyday human needs can be upgraded to eternity. At this point, Rabbi Shimon finally relents a bit.” (Shabbat 33b)

Rabbi Jachter wrote that Binyamin “understands the significance of Shabbat in this story based on Rashi to Bereishit 1:1, which teaches that Hashem at first planned to run the world based on pure middat ha’din (strict judgment). In Bereishit 1 only the name Elokim is used, signifying middat ha’din. However, Hashem realized the world could not be sustained in this manner and therefore partnered middat ha’rachamim (attribute of mercy) with middat ha’din.”

A particularly challenging story from the Aggadah is the one relating to Marta bat Beitus, a rich woman who lived in the late second Temple period, during the time of Bar Kamtza. She was one of the richest women in the city, and as the story goes, she sent her servant out multiple times in a given day. First, she sent him to buy fine flour, but he could not find any and returned empty-handed. By the time she sent him back out to buy white flour, it was already sold out. The same thing happened when she sent him out to buy dark flour, then barley flour, with no success. Finally, when she decided to leave on her own to find something to eat, she went outside without wearing shoes, stepped in some dung and died of shock. “Rabban Yochanan ben Zakai thus applied to her the Biblical verse, ‘The tender and delicate woman among you would not adventure to set the sole of her foot upon the ground…’” (Devarim 28:56)

So, one might ask: Is this simply a treatise on why women must wear shoes outside? No, say the Jachters. “The most basic objective of the story is to teach how quickly the situation went from the finest of food being available to none at all,” they write. This situation is the converse example of salvation from Hashem, when rescue comes swiftly and unexpectedly. “Examples include leaving Mitzrayim (Shemot 12:33) and Yosef being rushed to the palace to interpret Pharaoh’s dreams (Breishit 41:15 with commentary from Sforno).”

Alternatively, the Gemara could be teaching that the rigid thinking exhibited by the foolish behavior of the servant, who somehow never bought anything before it ran out, could lead to disaster. Or, perhaps Hashem deliberately caused the servant to act foolishly (Yeshayahu 44:25) as a punishment to Marta. Nevertheless the question remains: What was the sin that caused her to die under such pathetic circumstances?

While there are many possible reasons, the final conclusion drawn by the Jachters is a “vital lesson for Jews beginning the long journey of exile,” warning against narcissistic or selfish behavior: “That Rabbi Yochanan ben Zakai seeks to communicate to the community that one who greatly helps the community will be amply rewarded…. By contrast, Marta’s self-centered attitude led to her sudden downfall.”

“The Aggadic Mindset” is available on Amazon and wherever Jewish books are sold.

By Elizabeth Kratz