Many aspects of the Jewish calendar were historically placed under the control of the Jewish court, which in turn allowed them to decide when festivals occur. Vayikra 23:2 and 4 discuss “the moadim (set times) which you shall call (אֲשֶׁר־תִּקְרְא֥וּ) in their appointed times,” and Chazal understand these to refer to intercalating the year (meaning adding a leap-month) and declaring the beginning of each month based on eyewitness testimony.

A brayta in Sanhedrin 12a discusses how, in years of famine, the courts should not add that extra month. The pragmatic concern is that a second Adar delays Pesach in Nissan, delaying the omer offering which permits new grain.

Another brayta supplies the reason. As background, II Melachim 4 describes how there was a famine in the land, and at Elisha’s command, his students made a stew from wild gourds they had collected. It was poisonous, but Elisha fixed the issue by throwing flour into the pot. Then pasuk 42 reads: “A man came from Baal-shalishah and he brought the agent of God some bread of the first reaping—twenty loaves of barley bread, and fresh ears of grain in his sack. And [Elisha] said, ‘Give it to the people and let them eat.’” There wasn’t enough for 100 people, but Elisha told his students to set it out anyway, and it sufficed, with leftovers.

Rabbi [Yehuda HaNasi] analyzes pasuk 42. Baal Shalisha was the swiftest part of the land of Israel for produce to ripen, but only one species had ripened, as it mentions barley bread, rather than the expected wheat bread. Elisha told them to set the food before the people, so this new grain must have been permitted, after the omer offering. Thus, Elisha must have chosen not to intercalate the year, because of the famine.

Pivoting on a Verse

I studied this text in Sefaria, and I have some technical advice to share. I’m always encouraging studying parallel sugyot, but those are not always so easy to find. Sefaria has a wonderful feature that lists similar passages across the Talmud, based on significant word overlap, but for various reasons, the Yerushalmi parallel isn’t listed here.

In such situations, I “pivot” based on some other text. For instance, I might scroll up to the Bavli’s Mishna and see on the sidebar the Mishna listed, but not the Yerushalmi. I open up that Mishna, and on its sidebar I will see the Yerushalmi’s Mishna. Then, I can read the Yerushalmi parallel.

In this case, I pivoted based on the verse. That is, I selected II Melachim 4:42, and on its sidebar, four sugyot showed up. One was our sugya in Bavli and another was in Yerushalmi Sanhedrin 1:2. (While Bavli simply lists a massive Mishna at the start of the perek, Yerushalmi actually splits it up, so this is upon the second Mishna.)

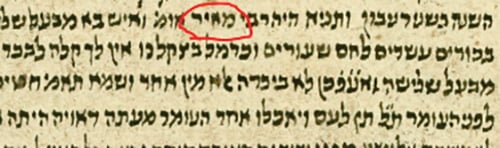

Why care about parallels? Well, the Yerushalmi’s brayta begins הָיָה רִבִּי מֵאִיר אוֹמֵר. Rabbi Meir was a fifth-generation Tanna, and a teacher of plain Rabbi, who is Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi. We care about correct attributions, so who actually said it? It turns out that while the printings (Vilna, Venice, Barko) and Reuchlin 2 manuscripts have just “Rabbi,” many other manuscripts (Florence 8-9, Yad HaRav Herzog, Reuchlin 2 , Munich 95, and the Oxford: Heb. c. 17/60 fragment) all have “Rabbi Meir,” matching the Yerushalmi. The omission of “Meir” transforming the speaker into Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi was a scribal error.

Building Connections

Knowing Rabbi Meir said it might help place the law and drasha in context. For instance, a bit earlier in Sanhedrin 11b, a brayta stated that the year is intercalated for three matters: the ripening of grain (if the grain isn’t yet ripe, there’s no omer-based delay for chadash); the fruit of the trees; and for the autumnal equinox (so that it will precede Sukkot). This is only if at least two of the three concerns pertain. When the grain ripening is one of the reasons, everyone’s happy. Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel for the equinox.

The Babylonian Talmudic Narrator notes that the Amoraim or Savoraim wonder whether Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel’s “for the equinox” meant that everyone’s happy if that’s the reason or if that reason alone is sufficient to intercalate the year. The conclusion is teiku—the question stands. Now, the parallel Tosefta Sanhedrin 2:2 and the parallel Yerushalmi Sanhedrin 1:2 have רַבָּן שִׁמְעוֹן בֶּן גַּמְלִיאֵל אוֹמֵר אַף עַל הַתְּקוּפָה. Without אַף, it works well to say that it indicates just one reason, contrasting with the anonymous Tanna Kamma who requires two. With אַף, it’s a strange contrast and seems like a reaction to the aforementioned happiness. There’s research indicating that the Bavli’s Talmudic Narrator was unaware of the Tosefta. This might be further evidence.

Now, Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel is likely the second Tanna by that name, a fifth-generation Tanna. The anonymous first Tanna is presumably his contemporaries, other fifth-generation Tannaim such as Rabbi Meir, Rabbi Yehuda and Rabbi Shimon. Meanwhile, we can view our brayta about famine as reactionary to the earlier brayta. While generally, any two signs suffice to intercalate the year, if the first sign is absent (for the ripening already happened) and the situation is dire (in case of famine), that suffices to block intercalation. That our brayta’s speaker is not Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi, the son of Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel II, but one of the fifth-generation disputants, Rabbi Meir, adds to our understanding of the dispute.

Also, when “pivoting” on the pasuk in Melachim, we can see how it is interpreted across the Talmud. In Ketubot 105b, a man who had a case before Rav Anan, a second-generation Babylonian Amora, brought him a basket of fish as a gift. Rav Anan was concerned because of the possible corruption of his judgement. The man cited this verse from Melachim about the gift homiletically, reading the לֶ֤חֶם בִּכּוּרִים֙ not as actual bikkurim, since Elisha was no Kohen, but as if they were bikkurim since Elisha was a Torah scholar. Rav Anan accepted the gift but forwarded the case to Rav Nachman.

In Menachot 66b, a brayta analyzes various verses pertaining to bringing the omer offering, leading with a dispute between the Tanna Kamma (thus Sages) and Rabbi Meir, a fifth-generation Tanna. Separately in the brayta, they define the omer offering as karmel, as a contraction of rach umal, soft and malleable. In this context, they invoke the pasuk in Melachim, with וְכַרְמֶ֖ל בְּצִקְלֹנ֑וֹ, “and fresh ears of grain in his sack,” reinterpreted as ba, “he came for us,” veyatzak lanu, “and he poured for us, and we ate,” venaveh haya, “and it was fine.” Again, dating this brayta to fifth-generation Amoraim, it’s meaningful that Rabbi Meir is part of the conversation.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.

1 Tosefta Sanhedrin and Yerushalmi Sanhedrin also have “three simanim” rather than “three matters”, perhaps indicating alignment to the natural order and the solar calendar instead of pragmatic concerns.