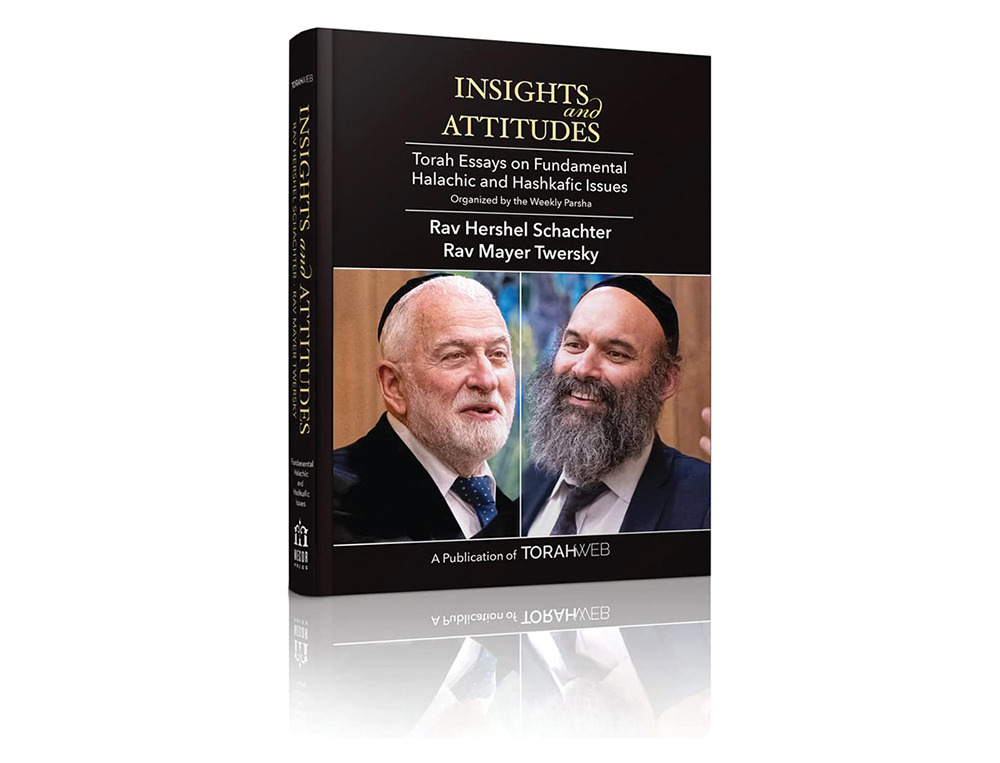

Editor’s note: This series is reprinted with permission from “Insights & Attitudes: Torah Essays on Fundamental Halachic and Hashkafic Issues,” a publication of TorahWeb.org. The book contains multiple articles—organized by parsha—by Rabbi Hershel Schachter and Rabbi Mayer Twersky.

In one pasuk at the end of parshas Va’eschanan (7:3), the Torah prohibits both forms of intermarriage: a Jewish man may not take a non-Jewish woman, nor may a Jewish woman marry a non-Jewish man. In Shulchan Aruch (Yoreh Deah, 157:61), the opinion of the Ramban (Milchamos, Sanhedrin 74) has been adopted, that there is a big difference between the two aforementioned cases. Because in the case of a Jewish man taking a non-Jewish wife, the children will not be Jewish, this prohibition is considered more serious; it is considered as though the man had become a mechutan with the avodah zara. This is the end of the line! The tradition of Jewishness transmitted from Mount Sinai from generation-to-generation will not be able to continue. But when a Jewish woman marries a non-Jewish man, the children will be Jewish; the transmission of Jewishness will continue. The woman has violated a serious aveira, but this is not a case of יהרג ואל יעבור.

In Europe, the common practice was that when a Jewish man would marry a non-Jewish woman, this was considered equivalent to his converting to another religion (shemad). However, when a Jewish woman married a non-Jewish man, the custom was not necessarily so. This aveira was not considered the equivalent of shemad.

Whenever there is a mixed marriage between two Jews, for example when a Kohen or a Levi marries a girl who is not a Kohenes or a Leviya, the status of the children is determined by the father. The same is true when there is a mixed marriage between two non-Jews. Amaleki, Edomi, Mitzri and Canaani each have a special status according to the halacha. When there is a mingling between two nationalities, the halacha declares that all the children follow the nationality of the father. This halacha is based on the pasuk in parshas Bamidbar (1:2) למשפחתם לבית אבתם which implies that in cases of a conflict, the mishpacha of the father is to be followed. The only exception is when there is a mixed marriage between Jew and non-Jew.

In Talmudic times, none of the rabbis felt that in these cases the status of the children should be determined solely by the father. One opinion felt that in order to be Jewish, one must have both a father and a mother who are Jewish. A second opinion held that with either parent being Jewish, all the children would be considered Jewish. And the accepted opinion is that the issue is determined solely by the mother (Tosafos, Yevamos 16b, s.v. oved kochavim, and Rabbi Akiva Eiger (Gilyon Hashas ad loc.)). This position was arrived at based on the rabbis’ careful reading of the pesukim (Devarim 7:3-4) at the end of our parsha. The Reform movement’s renunciation of this position was a rejection of a tradition that has been accepted for over 1,500 years.

It is interesting to note that in a marriage between a Jew and a non-Jew, none of the rabbis felt that the status of the children should be determined by the father. If in the other two types of mixed marriages (where both parents are Jewish or where the parents come from two different non-Jewish nations), the halacha established that everything is determined by the father, what motivated the rabbis to assume that the same should not be the case when a Jew and non-Jew marry?

The answer lies in the wording of the pasuk in Bamidbar (1:2). The status of the children is determined solely by the father when we’re dealing with an issue of mishpacha. Being a kohen or levi is an issue of mishpachas kehuna or mishpachas leviya. The same is true regarding Amaleki, Edomi, etc. We, colloquially, refer to these groups as “nationalities,” but strictly speaking (halachically), they are merely “mishpachos.” In order to be a member of a certain mishpacha, you must have yichus of בן אחר בן through your father. Being Jewish, however, is not a function of which mishpacha one belongs to. This is illustrated by the institution of geirus. After conversion, a ger belongs to no mishpacha, but, nonetheless, is just as Jewish as all other Jews. Being Jewish is a function of belonging to the Jewish people (Am Yisrael). The Jewish people are the only ones called a nation as such!

ומי כעמך ישראל גוי אחד בארץ (Shmuel II, 7:27).59

The rabbis, apparently, assumed that since “mishpacha” and “am” are fundamentally different, it must be that inclusion in each one will be determined by different factors in the case of a mixed marriage. A major difference between a “mishpacha” and a “nation” is that a mishpacha consists of a collection of individuals who relate to each other in a special way, while the term “goy” (nation) comes from the word “geviyya” (body). Klal Yisrael is considered “one body.” We must adopt this attitude and act accordingly.

59 See “Chillul Hashem,” above in this volume, Parashas Emor, page 165, where we explained in a similar vein why the actions of one Jew are seen as a reflection on all Jews, as opposed to other nations, for which the actions of an individual are not understood as such.

Rabbi Hershel Schachter joined the faculty of Yeshiva University’s Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary in 1967, at the age of 26, the youngest Rosh Yeshiva at RIETS. Since 1971, Rabbi Schachter has been Rosh Kollel in RIETS’ Marcos and Adina Katz Kollel (Institute for Advanced Research in Rabbinics) and also holds the institution’s Nathan and Vivian Fink Distinguished Professorial Chair in Talmud. In addition to his teaching duties, Rabbi Schachter lectures, writes, and serves as a world renowned decisor of Jewish Law.