One of the arguments supporting the notion that Mt. Sinai is in Saudi Arabia is that Moshe was living in מדין when he first went there, and מדין is in Saudi Arabia. As I discussed last week, there are numerous reasons why Moshe would have traveled far from מדין to Mt. Sinai, and the Sinai Peninsula being far from מדין may actually be an argument for the Sinai Peninsula rather than against it. But there are other arguments made for Saudi Arabia.

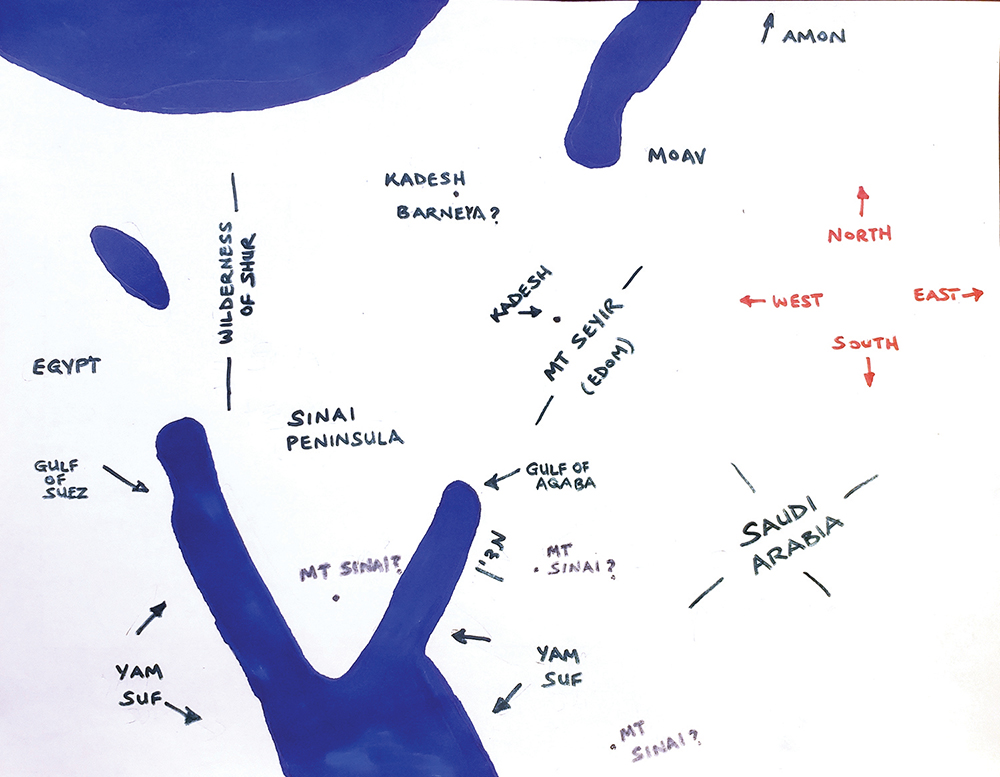

Some argue that the Sinai Peninsula was almost always under Egyptian control, so if the Children of Israel left Egypt, they couldn’t have been on it, and the sea they crossed (to leave Egypt) must have been the Gulf of Aqaba (crossing into Saudi Arabia) rather than the Gulf of Suez (crossing onto the Sinai Peninsula). However, the ancient Egyptians didn’t consider the Sinai Peninsula part of Egypt, and their “wall of fortresses” (preventing slaves from escaping and foreigners from entering) was between Egypt and the Sinai Peninsula. Besides, entering the Wilderness of Shur—the northwestern part of the Sinai Peninsula—after crossing the sea (Shemos 15:22) means they must have crossed the Gulf of Suez. Camping by the sea a few stops later (Bamidbar 33:10) also indicates that this is what they crossed, whether they stopped farther south on the eastern coast of the Gulf of Suez or at the tip of the Gulf of Aqaba.

The description of what happened when the Torah was given (thunder and lightning, smoke, fire and the entire mountain shaking, see Shemos 19:16/18) and when Eliyahu went to Choreiv (a strong wind that smashed the rocks of the mountains, followed by an earthquake, fire and faint sounds, see Melachim I 19:11-12) is also used to support a Saudi Arabian location. Shimon Ilani, a volcano expert who spoke at a 2013 colloquium on the location of Mt. Sinai (quoted in the March/April 2014 edition of BAR), said that “the shattering gust of wind, the quaking and rumbling, the fiery conflagration, all emitting from an imposing peak, evoke nothing so much as a shattering initial volcanic explosion, followed by violent shuddering and a fiery exhalation, abating after the eruptive force is spent. The sequential description of wind-earthquake(-noise)-fire-silence is very close to what happens during an explosive volcanic eruption.” There has been volcanic activity in Saudi Arabia, but not on the Sinai Peninsula (at least not recently; the southern mountains of the peninsula were formed from volcanic rock), so if the experiences described were the result of a volcanic eruption, it was more likely to have occurred in Saudi Arabia.

However, just as the “burning bush” was not consumed by the fire (Shemos 3:2), God descending upon Mt. Sinai likely did not take any physical form either. Besides, if there was a real volcanic explosion, Moshe, Aharon, Nadav, Avihu and the 70 elders (see Shemos 24:9 and 19:24) would not have survived, nor would Moshe have brought the nation closer to the mountain (19:17) rather than moving them out of harm’s way. Therefore, the possibility of volcanic activity shouldn’t be a factor.

It’s an “11 day trip from Choreiv (Mt. Sinai) to Kadesh Barneya, taking the road to Mt. Seyir” (Devarim 1:2). Since Mt. Seyir is northeast of the Sinai Peninsula, while Kadesh Barneya is directly north of the peninsula, why take the road to Mt. Seyir to get from the Sinai Peninsula to Kadesh Barneya? Conversely, since Mt. Seyir is northwest of Saudi Arabia, it makes sense to take the road to Mt. Seyir and then go farther west to Kadesh Barneya. Nevertheless, taking “the road to Mt. Seyir” doesn’t necessarily mean taking it all the way to Mt. Seyir, just as taking the highway that goes to Tel Aviv from Jerusalem to get to Beit Shemesh doesn’t mean going all the way to Tel Aviv. Besides, “the road to Mt. Seyir” didn’t reach Mt. Seyir (Carta Atlas Bible, map 10); it goes from the southern part of the Sinai Peninsula to the northern tip of the Gulf of Aqaba, where it meets other major roads, including one that goes past Mt. Seyir (“The King’s Highway,” see Bamidbar 20:17). The Children of Israel took a different connecting road, “the road to the mountains of the Emori” (Devarim 1:19), to continue to Kadesh Barneya.

In Kadesh, Moshe sent messengers to Edom, asking for permission to pass through their land (Bamidbar 20:14-19). Cutting through Edom must have made it a shorter trip to the Promised Land, and Edom’s refusal forced the Children of Israel to take a longer route. Since Edom is southeast of Canaan, and northeast of the Sinai Peninsula, if the nation was “wandering” on the peninsula, there’s no need to go through Edom to get to the Promised Land. If, however, they were in Saudi Arabia, which is southeast of Edom, passing through Edom (east to west) would cut down on their travel time. Nevertheless, since they had previously been west of Edom (in Kadesh Barneya), getting there obviously didn’t require Edom’s permission. Besides, it’s clear that Kadesh is west of Edom, as in order to circumvent Edom the Children of Israel traveled south, towards the Yam Suf, before turning north and continuing east of Edom (see Bamidbar 21:4 and Devarim 2:1-3/8). If Kadesh was east of Edom, there’s no need to go south; they should have just gone north to get to the Plains of Moav.

This doesn’t prove that Mt. Sinai isn’t in Saudi Arabia, only that when Moshe asked Edom for permission to pass through, he was asking to go west to east. Nevertheless, the way Yiftach related this request to the king of Amon (Shoftim 11:16) does indicate that the Children of Israel never entered Saudi Arabia.

Yiftach told the king of Amon, “When they ascended from Egypt, Israel went in the desert until the Yam Suf and they came to Kadesh.” His point was that had Edom and Moav given permission to pass through their lands, the Children of Israel wouldn’t have conquered anything east of the Jordan River (including the land Amon claimed was wrongly taken from them). They only went past (i.e. east of) the Gulf of Aqaba (the Yam Suf) because they were forced to go around Edom, and had to conquer land east of the Plains of Moav in order to create a passageway to the Promised Land. If Mt. Sinai was in Saudi Arabia, this statement wouldn’t be true, as they would have traveled past the Gulf of Aqaba long before they made their request. It would therefore seem unlikely for Mt. Sinai to be in Saudi Arabia (or Jordan).

Rabbi Dov Kramer is saving what some consider the strongest argument that Mt. Sinai must be on the Sinai Peninsula for next week. However, if you look closely at the map, you might be able to figure out what it is.