There are so many curricular areas and subjects for students to master, so how does a school choose to prioritize them? Where is the decision making and emphasis placement determined? Who makes these decisions? How much external input is sought or even encouraged? These are weighty decisions which speak to the entire enterprise of Jewish education in Jewish schools.

There is so much knowledge to be mastered and so little time to do it. Extending the school year or the school day seems to be a non-starter in schools with active extra-curricular activities and sports teams. Schools on the far right of the religious spectrum have their priorities clear. Their emphasis on limudei kodesh inhibits all but basic secular subjects and allows for a six day school week, including evening beit medrash sessions.

Centrist day schools grapple with time constraints and the desire to offer a comprehensive curriculum.

Every day school covers the basics. But does the definition of “the basics” change over time? The State mandates certain curricular areas. Schools can and do add courses and programs, and opportunities for students to select areas of interest beyond required courses. This includes more time studying limudei kodesh as well. We can argue about time allocation and prioritization for Jewish and general studies, and every school engages in this debate from time to time. However, I wish to raise one issue which has been touched upon often in the past but needs to be raised again—Israel education.

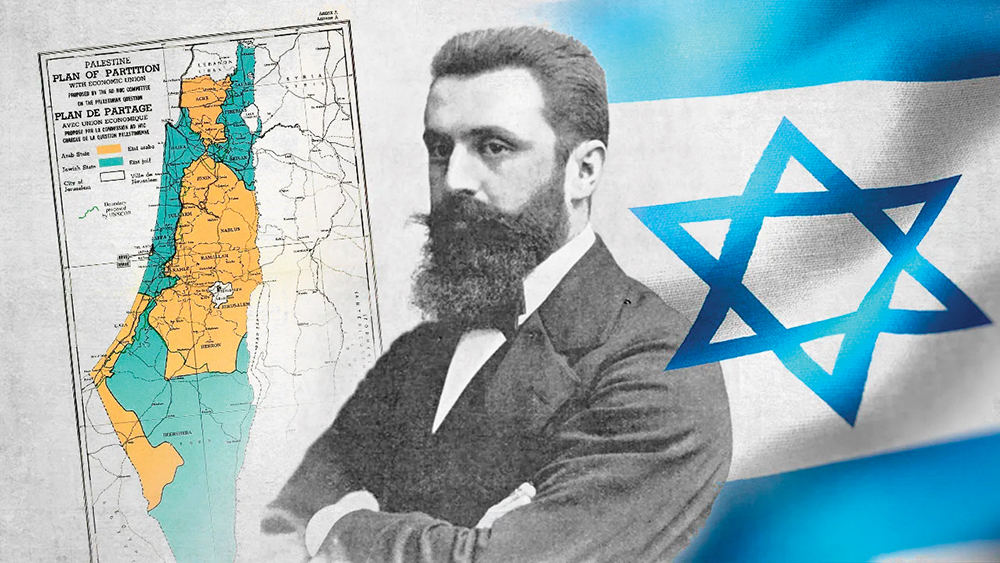

Given what is going on in the world today, the events taking place in Israel make this a priority. I am not just talking about knowing how to refute anti-Zionist arguments on the college campus or in the press or Facebook. There is a serious need for people—students who have grown up—to know Zionist history from the sources. Surface knowledge of some data and facts will not suffice. High school students will become college students and then adults who will live in a world where there will always be those who challenge Israel’s right to exist. Adults who support Israel’s right to exist must know the facts and the sources.

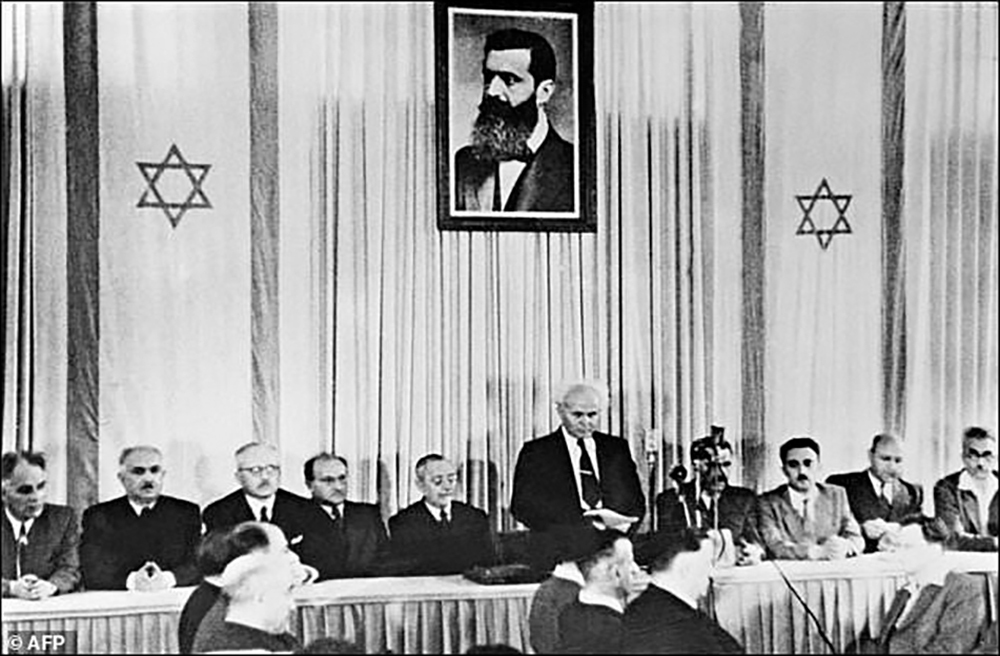

In the same way that we teach children to read Rashi script, we need to start early to teach about Israel—from Biblical times to the present. This is not a one-semester course nor a Yom Ha’Atzmaut project. Just as students progress from Chumash to Mishna and Talmud, so too they can be introduced to foundational texts, to the early Zionist theorists, historical sources, maps, Abba Eban’s speeches in the U.N., Menachem Begin and others. There is no shortage of materials in Hebrew and English.

We need schools to adopt programs and coursework and materials that introduce nuance into the portrayal of Israel. Schools need to present the dynamic complexities of Israeli society and even, I daresay, the Palestinian perspective. You cannot understand contemporary Israel without knowing something about her neighbors.

The mechanics of doing this will differ from school to school. Time allocation and position in the curriculum will vary. For some it may be a stand-alone course offered each year. Others may weave it into social studies, Hebrew language, history or political science. Wherever it winds up, the important issue is that it be addressed. Too many people have opinions about the matzav, the situation in Israel. Too few really have the knowledge and background to back up these opinions. Unfortunately, it’s become part of Jewish literacy as much as some academic aspects of our heritage.

Rabbi Dr. Wallace Greene is an eminent educator, lecturer and day school consultant.