By Rabbi Hershel Schachter

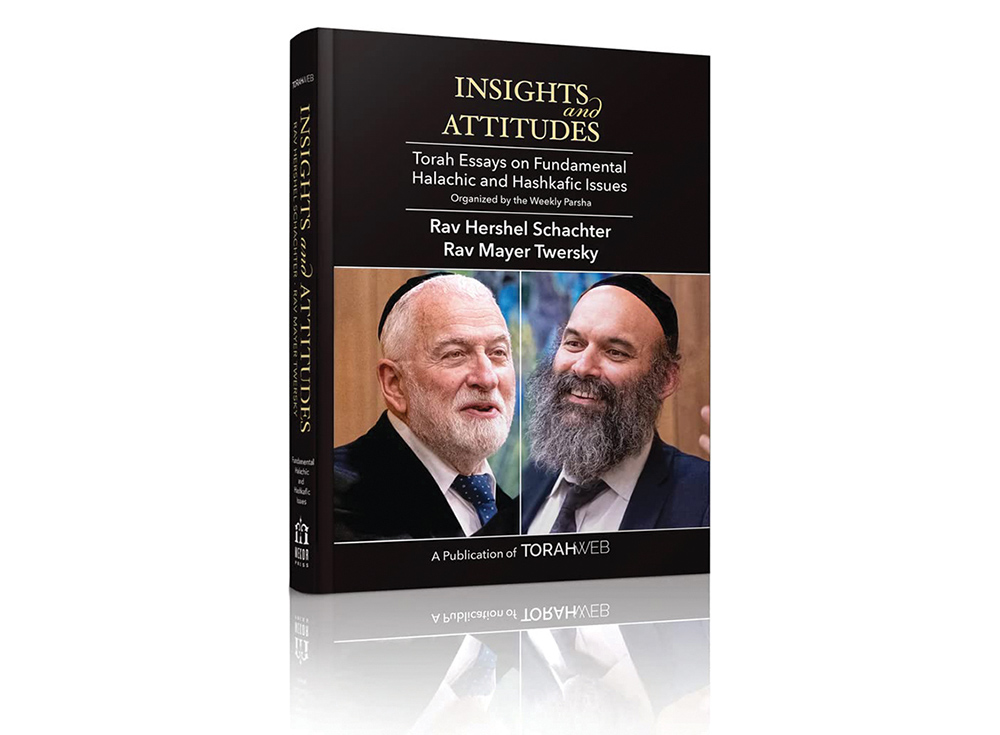

Editor’s note: This series is reprinted with permission from “Insights & Attitudes: Torah Essays on Fundamental Halachic and Hashkafic Issues,” a publication of TorahWeb.org. The book contains multiple articles—organized by parsha—by Rabbi Hershel Schachter and Rabbi Mayer Twersky.

The rabbis in the midrash saw a connection between the end of parshas Shelach (where the mitzvah of tzitzis appears) and the beginning of parshas Korach (which describes the rebellion against the authority of Moshe Rabbeinu). Korach claimed that since all Jews have the same level of kedushah, everyone has the right to interpret the halacha as he sees fit. His argument against Moshe’s halachic position had great appeal to the masses. It was based on common sense. Korach got 250 Jewish leaders to wear four-cornered garments made of techeiles and to appear before Moshe, asking whether it was necessary to tie the techeiles strings (in tzitzis) to their garments. Common sense dictated that this was not necessary. If one string dyed with techeiles takes care of a garment of any other color, then if the entire garment consists of techeiles strings, no additional strings of techeiles ought to be needed.

Moshe Rabbeinu—on the other hand—argued that halacha is a self-contained discipline where common sense does not always play a role. In the discipline of biology, the Talmud (Chullin 48b) points out that one cannot always use common sense; and the same is true of physics. Each discipline is self-contained and has its own style of logic. The same is true of the halacha.

This idea is well-known at yeshiva. Rav Soloveitchik’s talk on this topic has appeared both in “Shiurei HaRav,” (edited by Joseph Epstein) as well as in “Reflections of the Rav,” volume 1 (by Rabbi Avraham Besdin).

In connection with this idea, many will refer to the words of the Sema (in his commentary to Choshen Mishpat) that the seichel of the baal habayis is just the opposite from the seichel of the Torah (in yeshiva parlance: a “baalebatishe sevara” usually refers to a “common-sense argument”). In yeshiva circles, a witty comment is attributed to the Ohr Sameach: “when a talmid chacham cannot figure out any given halacha, let him ask a baal habayis and then do the opposite.” The halacha will always be the opposite of what the baal habayis thinks that it should be. The story goes that on one occasion, the talmidei chachamim did not know what the halacha should be in a certain instance, they asked a baal habayis, and he happened to give the right answer. They approached the Ohr Sameach and asked him, “But didn’t you tell us that the seichel of the baalei battim will always be the opposite from the seichel of the Torah?” Whereupon he answered that the baal habayis must have had a bad day! He was not thinking straight for a baal habayis!

I remember there was a student in Rav Soloveitchik’s class at yeshiva who would evaluate the shiurim. When everything made sense, there were no loose ends—and everything fit into place—that would be considered so-so. But when the sevaros developed were not that compelling, and all the Gemaros didn’t really fit in well, that was tops—“real Brisk!”

In fact, in Lithuanian yeshivas, there was such an exaggerated disdain for baalei battim, that the “story” went around about two elderly gentlemen—baalei battim, of course—who were both hard of hearing and made up to learn Gemara together. One was using a Gemara Eruvin, while the other was using an Arachin. The chavrusa went very well, until they reached the 43rd daf, when one was already making a siyum on the smaller volume (Arachin), and the other still had another 70 blatt to go!

This exaggerated attitude is the basis of the very fundamental philosophical question that bothered many of the Lithuanian yeshiva bochurim: Why did the Borei Olam create baalei battim at all? We know that He didn’t create anything that has no purpose!?

Needless to say, all of these exaggerations are ridiculous. The Sema never meant to say that the seichel of baalei battim is always the opposite of seichel haTorah. A layman who is not familiar with the intricacies of physics or biology will often be mistaken if he applies common sense to those disciplines, and the same is true of the self-contained discipline of Torah. But very often we will use common sense in establishing halacha! The Talmud (see, for example, Bava Kamma 46b) tells us that—by way of sevara—we can establish a din deOraisa!

I recently met a young talmid chacham who insisted that a certain halacha in Shulchan Aruch must be understood literally—as applying in all cases—even when it made no sense. I argued that it was self-understood that one should use his common sense, and only apply the halacha when it, indeed, did make sense. (I later checked the Iggeros Moshe of Rav Moshe Feinstein, and he wrote exactly the same in that particular instance.) This young talmid chacham told me, “No, we may not use common sense at all,” and even though the halacha—as he misunderstood it—made no sense, he has “emunas chachamim.” I told him that this was a Christian concept (the principle of the infallibility of the poseik). Our Torah (Vayikra 4:13-21) speaks of the theoretical possibility of a פר העלם דבר של ציבור—“a korban brought in a situation where all 71 members of the Sanhedrin paskened wrong.” The Torah tells us that—on one occasion—Moshe Rabbeinu was about to issue an incorrect pesak, until he listened to his brother, Aharon, and corrected his position (Vayikra 10:19-20).

In our religion, are we not permitted—or better yet—obligated, to ask questions when we come across a halacha that makes no sense? Isn’t that what “lernin” is all about: to make sense out of the halacha?! Our Torah is a Toras emes: it corresponds to reality and does not contradict it! Rav Chaim Volozhiner would often sign off at the close of a teshuva,נתן לנו תורת אמת ובלתי אל האמת ענינו קל אמת—“the true God gave us a truthful Torah and we always have to try to be honest to discover the true meaning of the halacha.” If there are two ways to understand a halacha—one which makes sense and the other which does not—of course, we should choose the interpretation that makes sense!

Yes, indeed, emunas chachamim is a very fundamental principle in our faith: we believe HaKadosh Baruch Hu will give divine assistance to an honest and deserving talmid chacham that he should be above his personal negiyos in issuing a pesak; he will not have an agenda. But it doesn’t mean that we should believe in nonsense. Every exaggeration is by definition not true. It does not correspond to reality. The halacha is very nuanced because the world is very complex. Most simanim in Shulchan Aruch have many seifim. You cannot cover all the cases in one short statement. The challenge of “lernin” is to be able to formulate the halacha precisely—without any exaggeration leaning in either direction—with seichel.49

Rabbi Hershel Schachter joined the faculty of Yeshiva University’s Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary in 1967, at the age of 26, the youngest Rosh Yeshiva at RIETS. Since 1971, Rabbi Schachter has been Rosh Kollel in RIETS’ Marcos and Adina Katz Kollel (Institute for Advanced Research in Rabbinics) and also holds the institution’s Nathan and Vivian Fink Distinguished Professorial Chair in Talmud. In addition to his teaching duties, Rabbi Schachter lectures, writes and serves as a world renowned decisor of Jewish Law.