Students shared their personal experiences regarding on-campus advocacy, avoiding unnecessary escalation during a time of tension, and their thoughts on the future of their universities.

Editor’s note: A condensed version of the article will be published in The Jewish Link’s May 9, 2024 edition.

These past few weeks, campuses around the US have been teeming with unchecked antisemitism, and it has reached a boiling point as pro-Palestinian protesters have set up encampments and/or checkpoints in central locations, restricting Jewish students from entering or moving through such areas. To understand better what exactly is going on and what is going through the minds of students as they confront these virulent forms of antisemitism and anti-Zionism, The Jewish Link interviewed a variety of Jewish students from across the political spectrum on a handful of campuses around the US—Harvard, University of Michigan, Yale and Columbia—that have had encampments.

Josh Brown, a University of Michigan junior from Westchester, explained that he leads the activism committee of Wolverine for Israel (Wolverine is UMichigan’s mascot), the campus’s Hillel-affiliated pro-Israel student group. Brown also attends campus pro-Palestinian events and documents the goings-on on social media. “I’m at virtually every protest and demonstration that they do,” he explained.

While Brown said that he is happy to engage with students at these protests and discuss the conflict, the students have a policy of not speaking with Zionists. “They have a very strict ‘no engaging with Zionists’ policy, so there is generally a minimal amount of dialogue at their events,” he elaborated. Brown said that this policy has existed even prior to October 7.

Brown said that UMichigan is not as aggressive as places like Columbia and Yale in terms of protests, detailing that there are no physical altercations that he’s heard of between students. “That being said, we do have an enormous amount of anti-Israel and antisemitic content on our campus,” continued Brown, calling the antisemitism “unavoidable,” especially since the students made an encampment in the center of campus. He further described incidents of anti-Israel messaging—chalk, posters, and marches—that have taken place on campus recently. “There has been a complete saturation of anti-Israel and antisemitic content on campus since October 7,” said Brown.

When asked how he thought these messages are influencing the student body, Brown explained that there is a factor of social pressure to the messaging, explaining that the Tahrir Coalition—a coalition of 90+ student organizations, and one of the leading coalitions who are leading these encampments and protests—creates an “enormous amount of social pressure to absorb anti-Israel and antisemitic messaging,” due to how many student groups are involved. However, Brown continued by surmising that the majority of people on campus do not support the anti-Israel protests or movement.

Brown added that anti-Israel groups on UMichigan’s campus “have shown a consistent endorsement and support of violence and terrorism, and have held various events glorifying terrorists and terrorist organizations,” detailing several examples, both before October 7, in the immediate aftermath (both on the day of and several days afterward), and several months later, in which they justified and celebrated both the attack and the taking of hostages, honored convicted terrorists, circulated PFLP propaganda posters and co-sponsored events with Samidoun, an Israeli-designated terror organization, and worked with their affiliates.

Aharon Dardik, a sophomore at Columbia University who is from Gush Etzion, Israel, shared his more unique approach on the issue. He leads Columbia’s J Street organization, as well as Columbia University’s “Jews for Ceasefire” chapter. Dardik explained that Columbia’s J Street chapter focuses primarily on starting conversations within the Jewish community that promote more nuanced takes on the issue, and that this semester, J Street has brought in several speakers, including people who work with improving relationships and creating community dialogue between Jews and Palestinians in Judea and Shomron.

Dardik said that Columbia’s “Jews for Ceasefire” organization, which he leads, is closely aligned with the “If Not Now” movement, explaining that they “[serve] as a bridge between the Jewish community and the much larger and more public pro-Palestinian community on campus.” Dardik’s group spreads awareness throughout campus about a bilateral ceasefire, with Dardik explaining that he is in favor of “a bilateral ceasefire that returns all of the hostages in exchange for an end of the war, involving the beginning of diplomatic processes that involve a long-term peaceful solution, including demilitarization of Hamas.”

Dardik is hesitant to label many of the people identifying as “anti-Zionists” as antisemitic; he elaborated that, in every popular definition of antisemitism, a specific clause includes a clarification that criticism of Israel, even if it is anti-Zionist in nature, is not by definition antisemitic. He then clarified that there have “definitely been antisemitic incidents on campus,” although he argued that the label of antisemitism has been used as a “cudgel” toward these anti-Zionist movements. He further insisted that students in these protests are capable of determining what they are doing that is antisemitic: “People will be able to tell the difference between antisemitism and anti-Zionism if we as a community do a better job of defining each term and differentiating between them,” concluded Dardik.

Sahar Tartak, a sophomore at Yale from Great Neck, NY, recently was in the news after getting physically assaulted at a recent Yale protest. She described her activism as being primarily writing-based, saying that she released a controversial article in Yale Daily News shortly after October 7 called “Is Yalies4Palestine a Hate Group?” She wrote this article following large celebrations and justifications of October 7 by Yale’s student body, in which they chanted “resistance is justified” and called on other students to celebrate the “resistance” as a success. “Yale Daily News censored [my] article a few weeks later by cutting out references of Hamas raping and beheading people,” continued Tartak, “so I came out with an article about in Washington Free Beacon about them denying this atrocity.”

Tartak also testified to Congress in mid-November about her experiences on campus, and also wrote a piece in Tablet in early January that was “a more extensive discussion of how journalism, especially student journalism, has been corrupted by an ‘oppressor/oppressed’ dichotomy like the thing that happened in Yale Daily News with the denial of Hamas atrocities.” She said she writes mostly articles, and sometimes on Twitter, as well as appearing on the national news fairly often.

“More recently, I was assaulted at one of these rallies while being blockaded, and I wrote an article for The Free Press,” said Tartak. “Earlier this year, I ran a small paper magazine called The Yale Free Press that is delivered door-to-door, where I wrote a defense of Israel.” Tartak explained that the paper is more well-distributed than any other campus papers, as it hits nearly every door on campus. Tartak wrote an article in this paper about the process of Israel giving up the Gaza Strip, and how Hamas manipulates the media and the Western world about Israel. Another Yale student, who was born and raised in Iran, wrote an article in Tartak’s paper calling the Yale student keffiyeh-wearers “privileged,” comparing their rallies to the ones in Iran in which people were shot.

Tartak said the encampments are impossible to avoid, as they are located at the entrance of the central library and central dining hall on Yale’s campus. She explained that students either have to walk around the encampment or take a back door, as the students in the encampment won’t let others through. Tartak continued that, when she would record these encampments, she was tailed by members of the encampment afterward on multiple occasions. “The encampment in front of the library, they’d ask whether you agreed with the community guidelines, and at one point kicked out multiple Yale Daily News reporters from the encampment,” she said.

Shabbos Kestenbaum, a second-year graduate student at Harvard from Riverdale, is the founder and president of the Harvard Divinity School Jewish Student Association, as well as being an active member of Harvard’s Hillel and Chabad. “During October 7, [Harvard] had 34 student groups representing more than 1,000 students claim that Israel was responsible for October 7,” said Kestenbaum.

Kestenbaum said that he planted 1,200 Israeli and American flags in the center of Harvard Divinity School “to draw attention to the plight of the hostages and to draw attention to the fact that American and Jewish values align.” He has given speeches at rallies, and on the night of May 7, will be saying the names of all victims of October 7 in the center of the encampments through a loudspeaker. “I’ve organized and prayed in front of the illegal encampments with my tefillin, and said tehillim for the hostages,” said Kestenbaum.

Kestenbaum said that he, along with five other unnamed students, filed a lawsuit against Harvard in January alleging that “Harvard has allowed pervasive and systemic antisemitism across campus generally, and in a way that has been inescapable since October 7.”

Tartak and Kestenbaum both said that they think non-Jewish American media is downplaying the intensity and violence in these protests. “When I was at MIT on Friday, I wanted to walk through [the encampment], and 7 alleged ‘safety marshals’ with no authority and were students, physically prevented me, initially, from walking in,” said Kestenbaum. “I know students who don’t wear kippahs anymore, who don’t talk about their Israeli identity in classes. These are real, ongoing threats.” Tartak said that, although many people believe these groups to be peaceful, “they are clearly not,” continuing that the practice of creating human blockades to stop Jews upon arrival to the encampments “is a step toward violence” and restricts people’s freedom of movement. Tartak explained that the human blockades are common and have been happening on campuses across the US, and also said that people at these encampments will chant things like, “From water to water, Palestine is Arab”—a call for genocide. However, Dardik disagreed that Western media has been downplaying the protests, arguing instead that the media has exaggerated the rallies and encampments at Columbia, elaborating that “something big…is made massive,” because the media cannot accurately capture the nuances of an on-campus experience and merely wants to dramatize the protests. Although the media tries to create a general picture, it became clear that students living with encampments right now are having a large variety of experiences that cannot be painted with a broad brush.

When it comes to balancing advocating for his beliefs while avoiding escalation, Kestenbaum said that students are at university to learn and be educated, and that includes going outside of one’s comfort zone and engaging with ideas that make them uncomfortable. “Intellectual discourse, the free exercise and exchange of ideas, academic rigor, these are pillars of our educational experience, and I’d like to play a role in that,” he said. However, he acknowledged that his mere presence “instantaneously fans the flames,” as someone who is Jewish and knows many people fighting in the IDF. “I won’t apologize for my identity, but I will always advocate for respectful, peaceful, and non-violent discourse,” said Kestenbaum.

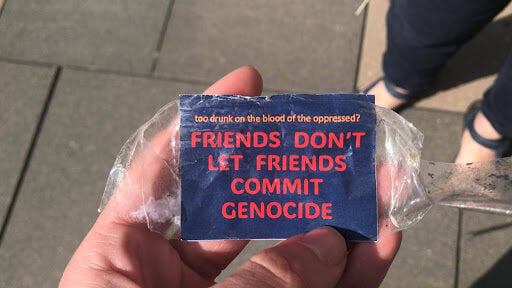

Tartak, meanwhile, explained that she thinks it’s most important to “just be honest” when it comes to advocacy: “If students on campus are calling for mass genocide or if they are justifying or celebrating mass genocide, which are the three things I’ve seen repeatedly since 10/7, you have to call it out,” she said. “I was not the person who put up stickers all over Yale’s campus that say, and I quote, ‘Too drunk on the blood of the oppressed? Friends don’t let other friends commit genocide.’”

Dardik said he approaches things on a “case-by-case” basis, in which his goal is to raise awareness of the issues he’s discussing, but also to encourage people to think critically about them. “Oftentimes, that means participating in a certain way in a larger movement, or by bringing smaller groups together that are more ideologically aligned, even if the people around me aren’t,” said Dardik, explaining that he will often participate in initiatives in which he tries to get people from the left and right wing of the political spectrum—both regarding Israeli politics and in general—to engage in discussions with one another.

Brown said that his group, Wolverine for Israel, attempts to “organize in a manner that is not antagonistic” and generally does not plan counter-protests. “I, along with other pro-Israel students, will sometimes stand silently with Israeli flags during some of the larger demonstrations,” said Brown, who explained that this initiative attempts to show a “Jewish and Zionist presence on campus” during some of the larger demonstrations with “pretty vile rhetoric.” He said that the purpose of the initiative is to try to ensure that Jewish and Zionist students know there’s a place in UMichigan’s community for them.

“When we do have large events, we ensure that we are following university policy and the law, unlike their demonstrations, and we do it in a manner that attempts not to be antagonistic toward their movement,” continued Brown. “We make every effort possible to avoid conflict while still being proud Jews and proud Zionists.”

What do you think can be done long-term to combat the antisemitism/anti-Zionism that has gripped your college campus, as well as campuses around America?

Kestenbaum said that Harvard, like any institution, should discipline antisemitism “the way they would respond to any act of hatred or discrimination,” adding that attaching real consequences to displays of antisemitism would be “a powerful response.” He also said that he met with members of Congress on May 6 to talk about “the power of the purse”: “These universities receive billions of dollars in federal subsidies,” explained Kestenbaum. “That taxpayer money should not be taken for granted. If students are not feeling accepted and safe, these universities shouldn’t be given the privilege of billions of dollars.”

Dardik said that he thought that administrative efforts to deal with the outbreak of antisemitism on Columbia’s campus have “completely failed,” saying that the university’s antisemitism task force will collect experiences from students regarding their experiences with antisemitism and then “sit on them and weaponize these experiences instead of trying to solve the problem.” He said that he thinks that appealing to the left’s hatred of bigotry, and driving the point home of antisemitism being a form of it, is “the most viable way forward.” He continued that it is hard to hold the movements accountable from the outside, because they don’t like listening to outside sources, “but they do listen to each other”; thus, he suggested attempting to carefully educate people within these movements on antisemitism.

Dardik continued that, as a Jewish community, “we need to educate ourselves more about what the pro-Palestine movement on these campuses is, what they want, and the differentiation between people who are genuinely antisemitic and those whom I think are much more moderate and really do care about all human beings, and are in this because they see it as a tragedy that so many Jews and Palestinians are dying.” Dardik said that he hopes that approaching people and discussing things in their language, while appealing to their liberal values, could work.

Tartak said that campuses need to bring in many Israelis to fill positions as administrators, faculty, staff, and students. “You need a bunch of leaders who actually know what terrorism is, rather than ones who take it lightly,” said Tartak. She also pointed out that the university administration was “negotiating with terrorists,” as she pointed out that the students at these encampments are funded by, relating to, cheering on, supporting, and using the language of terrorists. “The university should not be negotiating with them,” insisted Tartak. “They should be kicking them off with police forces, or by threatening them with suspension, which was an effective method at Yale…as soon as they threatened suspension, the students left the encampment.”

Brown said that the campus needs to deal with behavior and rhetoric, which he classified as “two different discussions.” He said that behavior such as “violating the law, breaking university policy, obstructing traffic, putting up posters where they’re not permitted to, and encampments” is behavior that must be combated by “enforcing existing policies that are available to administrators.” Brown pointed out that UMichigan already has an existing policy that respects free speech while forbidding disruptive protests, but it has not been enforced. “You have students who brazenly violate both university policy and the law, post on social media bragging about it, and face no consequences,” said Brown.

Regarding rhetoric, Brown said that professors and administration educate their students in ways that make them more anti-Israel, antisemitic, and misinformed on the conflict. “I think we can ensure that students are informed on the conflict and the realities of the conflict, and they are equipped to deal with propaganda and misinformation that is widely prevalent in many of these movements,” he explained. “You need to be able to think critically and be able to distinguish fact from fiction.”

Kestenbaum explained that Jews used to comprise 25% of Harvard’s student body, but the number has been reduced to 4%. “There was a deliberate decision to exclude Jews,” said Kestenbaum. Regarding the current situation, he said that the long-term consequences likely wouldn’t be readily felt because there aren’t enough Jews on campus to feel these consequences. “I think internally within the Jewish community, there is already a repudiation of these alleged elite universities…but I don’t think major institutions like Harvard, MIT, and Columbia will be impacted in any meaningful way, unless of course high-end donors get involved.”

Along the same lines, Brown said that, while UMichigan “has historically had an important place for Jews in America,” people were likely to think twice about attending UMichigan following its lack of action on behalf of its Jewish students. Tartak similarly wondered whether Jews would be less willing to attend Yale following its recent bout of antisemitism, but acknowledged that the “elitism” of the university might be enough to draw students to Yale anyway.

Dardik, meanwhile, said that “protest movements will come and go,” and that “we always overrate how much a movement like that will stay in the cultural zeitgeist.” However, he said that Columbia’s entire campus has been shut down, which has a “chilling and sobering effect,” and questioned whether the events of the past few weeks will permanently rupture relationships between Columbia’s student body and its administration.

Brooke Schwartz Bass is a junior at Brandeis University. Originally from Englewood, she is a graduate of The Frisch School and studied at Midreshet Amudim in Israel. She is also a former Jewish Link intern and staff member.