In Ketubot 84a, a mishna relates a dispute between Rabbi Tarfon and Rabbi Akiva. If Reuven dies and leaves a widow, a creditor, and heirs and has a deposit or loan held by others, who gets the money? Rabbi Tarfon awards it to the most needy of the claimants. Rabbi Akiva retorts that we aren’t merciful in judgment. Rather, it is given to the heirs, who have a stronger claim since they don’t require an oath before collecting. In 84b, some judges ruled like Rabbi Tarfon, and Rabbi Shimon ben Lakish reversed their judicial action. Rabbi Yochanan, his teacher-colleague, criticized him and said, “You are treating this like Torah law,” where we reverse judicial error.

The talmudic narrator assumes that Reish Lakish holds firm in the face of this criticism, and explores the point of conflict between these Amoraim. Possibly, Reish Lakish thinks the decision is reversed even by “טָעָה בִּדְבַר מִשְׁנָה.” Alternatively, both agree that such a decision is reversed, but they argue about who is right. (I find this difficult to reconcile with Rabbi Yochanan’s words, “עָשִׂיתָ כְּשֶׁל תּוֹרָה,” but this might be taken as saying, “You are treating Rabbi Akiva’s position as so correct like it is Torah law, when it isn’t so.”) Rabbi Yochanan maintains the halacha is like Rabbi Akiva over his individual colleague, but not his individual teacher. Reish Lakish maintains that “over his colleague” encompasses even a teacher.

Alternatively, both maintain that it isn’t inclusive of a teacher, but they argue whether Rabbi Tarfon was Rabbi Akiva’s colleague or teacher. Alternatively, they agree that Rabbi Tarfon and Rabbi Akiva were colleagues, but disagree whether this rule establishes the definitive halacha (“הֲלָכָה”) or just a preference to rule that way (“מַטִּין”).

Sourcing the Concepts

The talmudic narrator is bold yet humble, and almost always bases himself on ideas or principles stated by named Amoraim elsewhere. So, see Sanhedrin 6a where Rav Sheshet says “טָעָה בִּדְבַר מִשְׁנָה” is reversed, as discussed by Rav Safra and Rabbi Abba. So too, Rava in Shevuot 38b. One amusing sugya — and likely the trigger — is Sanhedrin 33a. A cow from Beit Menachem had its womb removed. Rabbi Tarfon had erroneously ruled it a treifa, so they disposed of the cow and fed it to the dogs. Rabbi Tarfon was distressed, fearing he was on the hook for the money. Rabbi Akiva reassured him that he wouldn’t. As discussed by Amoraim, including Rava and Rav Sheshet, the issue discussed by Rabbi Tarfon and Rabbi Akiva was partly whether “טָעָה בִּדְבַר מִשְׁנָה חוֹזֵר!”

Similarly, that holding like Rabbi Akiva over his colleague was stated by Rabbi Yaakov and Rabbi Zerika in Eruvin 46b. There as well, three of Rabbi Yochanan’s students argued about what this meant: Rabbi Asi said this meant “הֲלָכָה,” Rabbi Chiyya bar Abba said it meant “מַטִּין,” and Rabbi Yossi beRabbi Chanina said it meant “נִרְאִין.”

Rabbi Tarfon

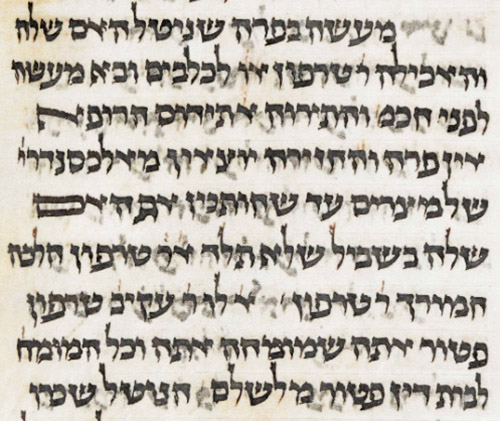

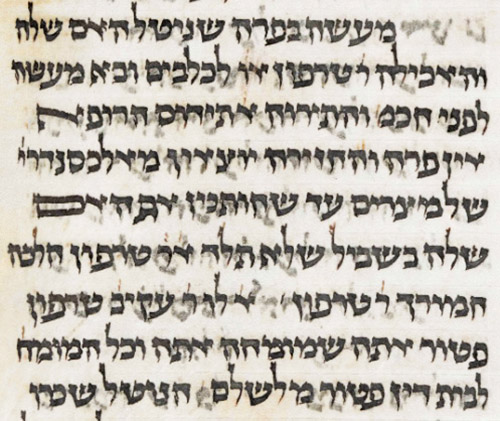

Why are we unsure whether Rabbi Tarfon is a colleague? We can examine how they referred to one another. Rabbi Tarfon calls Rabbi Akiva by the name “Akiva” (Kiddushin 66b; Zevachim 13a). Meanwhile, Rabbi Akiva chastises Rabbi Yehuda ben Nechemia for arguing with Rabbi Tarfon, calling Rabbi Tarfon a zaken (old) (Menachot 68b). Further, in Yerushalmi Yoma 1:2, he addresses Rabbi Tarfon as simply “רבי.” In the mishna involving the cow of Beit Menachem (Bechorot 28b), Rabbi Tarfon refers to himself as simply “Tarfon,” while Rabbi Akiva addresses him as “Rabbi Tarfon,” with the title. This is true in printings and some manuscripts. However, Vatican 120 skips the addressing entirely, and Munich 95 and British Library 402 have addressed him simply as “Tarfon.” The Kaufmann Mishna manuscript has “Rabbi Tarfon.” The mishna as cited in Sanhedrin 33a, however, omits the address entirely in printings and manuscripts — so the address in its various forms was likely added for clarity.

We, thus, have a slight indication of Rabbi Akiva treating Rabbi Tarfon as a colleague (“Tarfon”), but not anything persuasive. In contrast, in Mishna Yadayim 4:3, Rabbi Tarfon argues with third-generation Rabbi Eleazar ben Azarya and second and third-generation Rabbi Yehoshua ben Chananya, who refer to him as “brother Tarfon.” The unequal addressing suggests that Rabbi Akiva is the student.

What is their scholastic generation? This is an inexact science, but we can see their respective students. Rabbi Akiva lost his early students to plague, but his later students famously include the fifth-generation Tannaim, Rabbi Meir, Rabbi Yehuda, Rabbi Shimon and Rabbi Yossi. Meanwhile, Rabbi Tarfon’s students include the fourth-generation Tannaim, Shimon ben Azzai and Shimon HaTimni (Tosefta Berachot 4).

Some generational confusion may arise in that fifth-generation Rabbi Yehuda was a primary student of Rabbi Tarfon — having studied with him from a young age. In Megillah 20a, he relates how, as a minor, he read the megillah before Rabbi Tarfon and the elders in Lod. Rabbi Yehuda often describes interactions with Rabbi Tarfon or cites him.

Indeed, Niddah 24b describes a seemingly literal yeridat hadorot, descent of generations. Abba Shaul was a gravedigger and found himself standing in an eye-socket. He inquired of the Sages, who instead of telling him it was a fossilized dinosaur, told him it was the biblical Avshalom’s eye-socket. Lest we think Abba Shaul a midget, we are informed that he was the tallest in his generation. (Rav Hyman says he witnessed the Beit Hamikdash, and this puts him in the generation before Rabbi Tarfon.) Rabbi Tarfon (third/fourth generation Tanna) reached his shoulder. And (fifth-generation) Rabbi Meir reached Rabbi Tarfon’s shoulder, (sixth-generation) Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi reached Rabbi Meir’s shoulder, (transitional generation) Rabbi Chiyya reached Rabbi’s shoulder, (first generation Amora) Rav reached Rabbi Chiyya’s shoulder and (second-generation Amora) Rav Yehuda reached Rav’s shoulder, each being the tallest in their generation. While we might understand this figuratively as referring to scholastic stature and leadership, the talmudic narrator utilizes it literally. Regardless, we don’t move from Rabbi Tarfon to Rabbi Akiva, but jump to Rabbi Meir. This might be because of Rabbi Tarfon’s student, Rabbi Yehuda, or because his lengthy lifespan overlapped scholastic generations.

At the end of the day, I suspect we don’t need to make Rabbi Akiva, the talmid-chaver, (student-colleague) of Rabbi Tarfon. Rather, the talmudic narrator cited a principle, “הֲלָכָה כְּרַבִּי עֲקִיבָא מֵחֲבֵירוֹ.” Does “colleague” only mean one of his scholastic generation, a literal colleague? Or, does it mean any disputant — even if it happens to be his teacher or someone of a prior generation? That’s the core of the Gemara’s uncertainty.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.