I sold you a barrel of wine and it subsequently turned to vinegar. Who bears financial responsibility? Rav says that if it turned during the first three days following the sale, it’s on me, the seller, since the process of souring had begun; from then on, I’m off the hook. Shmuel disagrees and says I’m off the hook regardless. Perhaps it hadn’t begun souring in my domain, but אַכַּתְפָּא דְּמָארֵיהּ שָׁוַואר—“the wine soured/was agitated1 as you carried it on your shoulder.”

In practical court cases in the city of Pumbedita, Rav Yosef ruled like Rav when it came to soured beer and like Shmuel when it came to soured wine. Yet, immediately thereafter and without explanation, our sugya strangely states וְהִלְכְתָא כְּווֹתֵיהּ דִּשְׁמוּאֵל, that the halacha is like Shmuel (Bava Batra 96a-b). Even more strangely, the standard Rishonic halachic decision makers rule like Rav Yosef over the hilcheta.

What motivated Rav Yosef to split his decisions this way? Why doesn’t the Stammaic conclusion agree with Rav Yosef? Finally, why do the poskim ignore the Gemara’s own conclusion?

Split Decision

If Rav Yosef thinks one position is right, why doesn’t he rule consistently for both wine and beer? Several possibilities come to mind.

Rav Yehuda—a second-generation Amora who founded Pumbedita academy—was a long-time student of Rav and then, for 10 years, a student of Shmuel. Rav Yosef—a third-generation Amora—led Pumbedita academy and was Rav Yehuda’s student. As we see from longer citation chains (X quotes Y quotes Z), Rav Yosef learned Rav and Shmuel’s teachings from Rav Yehuda. I haven’t explored this sufficiently to find a pattern, but perhaps coming from this blended tradition causes Rav Yosef to give more weight to both Rav and Shmuel, in a way that his contemporary, Rabba bar Rav Huna would not—Rav Huna being a primary student of Rav.

Rashbam suggests that he rules like Shmuel regarding wine because of the mishna on the bottom of 97b, that states without any carve-outs that הַמּוֹכֵר יַיִן לַחֲבֵירוֹ, וְהֶחְמִיץ—אֵינוֹ חַיָּיב בְּאַחְרָיוּתו—“if one sold wine to his friend and it sours, he’s not liable for it.” Meanwhile, that mishna hadn’t discussed beer.

Tosafot—d.h. ושמואל אמר חמרא אכתפיה דגברא שוואר—attacks Rashbam on a different point, but their attack is actually a good reason for the split decision. Rashbam understood the spoilage on the buyer’s shoulder to be a function of the buyer’s mazal. After all, Rav Chiyya bar Yosef (a second-generation Amora who was Rav’s student and who, eventually, came before Shmuel) said on 98a that חַמְרָא—מַזָּלָא דְמָרֵיהּ גָּרֵים—“regarding wine, it’s the owner’s poor fortune that causes it to sour,” quoting a verse from Chavakuk. Tosafot objects that, if this is so, why should the Gemara categorize it as עֲבַד רַב יוֹסֵף עוֹבָדָא כְּווֹתֵיהּ דְּרַב בְּשִׁיכְרָא, that Rav Yosef acted (specifically) like Rav with beer, and like Shmuel with wine. Even Shmuel would agree with beer! We might answer Tosafot that indeed, Rav and Shmuel agree, but the name was a shorthand for the position. Rav Yosef heeds Shmuel’s objection, but only where it’s relevant.

Setting aside luck and following Tosafot that the concern is agitation, Shmuel was knowledgeable in various scientific fields. He specifically targeted חמרא as spoiling sooner due to the agitation. Perhaps Rav Yosef assumed that that natural process wouldn’t translate to beer, so only heeded Shmuel’s objection for wine.

Ruling Like Rav Yosef

Given this apparent three way dispute between Rav, Shmuel and Rav Yosef, how should we rule? We might conceivably apply different decisive principles. For instance, in a dispute between a teacher and student—especially in the earlier generations—we tend to rule like the teacher, and regard the student’s argument as only theoretical. Rav and Shmuel are first generation, against third-generation Rav Yosef’s, but they are grand-teachers. Rav Yosef saw fit to rule against one of them, or with them, in practical court cases, so it wasn’t merely theoretical.

Indeed, Rav Yosef’s practical rulings may form a “maaseh rav,” taking concrete actions based on halachic principles, which has greater force than mere staking out of a halachic position in the abstract. Further, the way this is phrased, that Rav Yosef ruled like X in these circumstances and like Y in these other circumstances fits a different pattern, that of a machria—someone who either compromises or states that X’s position is logical in case A and Y’s is logical in case B. There’s a rule that הלכה כדברי המכריע—though many Rishonim restrict this to a Tanna in a mishna, with disputants extending it to a baraita.

There’s a decisive principle that we rule like the authority of the later scholastic generation, who heard the arguments of earlier authorities and still weighed in. That principle is regularly applied to fourth-generation Amoraim (like Abaye and Rava) and on, while Rav Yosef is third generation. Finally, perhaps Rav Yosef is simply applying the rules as Shmuel would have decided it himself—in different wine/beer circumstances—as described above. It’s presented as a way of fulfilling Rav and Shmuel.

The Stammaic Ruling

The Talmudic narrator followed Rav Yosef’s split ruling with a statement that the halacha is like Shmuel. Maybe this is because this is a monetary matter. Except where we don’t, we rule like Rav in ritual matters and Shmuel in monetary matters (Bechorot 49b). Is this Talmudic narrator Rav Ashi—that he feels empowered to rule this way—or a Savora, Gaon or even later? Is he saying that despite Rav Yosef ruling like this in his own generation, we have this overriding principle?

Practically, the Smag, Rambam, Rif, Rosh, Tur and Shulchan Aruch all rule like Rav Yosef, and not consistently like Rav or like Shmuel. Curiously, they don’t even acknowledge the Stammaic statement that the halacha is like Shmuel, perhaps because that statement doesn’t exist.

Rav Shmuel Strashun (the Rashash) often deals with correcting the Talmudic text, and he points out that—based on what Rashbam writes later—Rashbam lacks the Stammaic passage of וְהִלְכְתָא כְּווֹתֵיהּ דִּשְׁמוּאֵל. Namely, the last Rashbam on Bava Batra 98a writes דהא שמואל קאי כוותיה ואמרן לעיל עבד רב יוסף עובדא בחמרא כוותיה דשמואל. That is, he assumes we rule like Shmuel in wine because of Rav Yosef’s statement, and doesn’t mention the וְהִלְכְתָא.

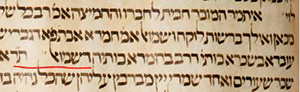

This seems right. Aside from other Rishonim omitting it, on the Hachi Garsinan website, only the printings (Vilna, Venice, Pisaro) have וְהִלְכְתָא. All of the manuscripts (Hamburg 165, Munich 95, Paris 1337, Escorial, Vatican 115b and the fragmentary CUL: Add. 1228) omit וְהִלְכְתָא. Perhaps it is dittography—that is, erroneous duplication—by a scribe of the end the preceding statement about Rav Yosef, וּכְווֹתֵיהּ דִּשְׁמוּאֵל בְּחַמְרָא; perhaps it was a marginal comment by a later figure that was copied into the main text, but regardless, it could plausibly be an extremely late (perhaps even Rishonic or Acharonic) interpolation.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.

1 See Rashbam who understands it as the “mazal—luck” of the buyer that caused it to sour, versus Tosafot who understands it as the agitation of transport causing it.