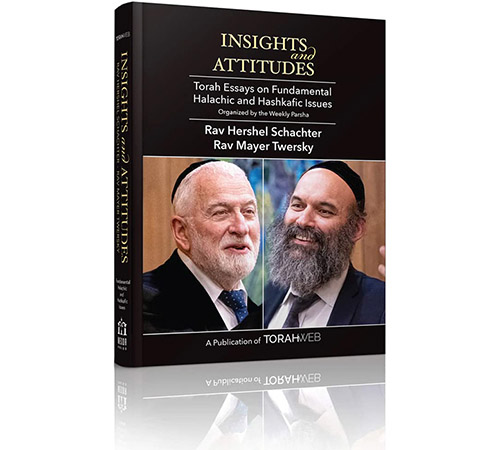

Editor’s note: We are proud to present a new series, reprinted with permission from “Insights & Attitudes: Torah Essays on Fundamental Halachic and Hashkafic Issues,” a publication of TorahWeb.org. The book contains articles by Rabbi Hershel Schachter and Rabbi Mayer Twersky.

Four very old minhagim are based on events described in Parshas Lech Lecha. One relates to the marriage ceremony, two to bris mila, and one to tying shoelaces as it relates to the wearing of tefillin.

When Avraham Avinu expressed his concern that he was already so old that he probably would not have any children of his own, God instructs him to go outside of his tent under the star-filled night sky. Hashem asked, “Can you possibly count all of the stars? So too will you have so many descendants that it will be impossible to count them all.” For many generations, it was the custom for a young woman to get married outside, in order to invoke the Divine blessing of having many children. When the woman getting married was older, and the couple was not expecting to have any children, the wedding ceremony would be held indoors. Some trace this practice back to the days of the Talmud (see Sefer BeIkvei HaTzon, p. 266).

When Avraham Avinu performed the mitzva of bris mila, the Torah tells us that Hashem gave him the entire land of Israel. An individual person, or even a family, certainly doesn’t need an entire land! Obviously Avraham would be the founding father of an entire nation, and the land would belong to that nation. Rav Yaakov Emden claims that our common custom of giving a gift to the ba’alei simcha upon the occasion of the celebration of a bris derives from this biblical narrative. We follow the lead of HaKadosh Baruch Hu, who gave this major gift (all of Eretz Yisrael) upon the occasion of the very first bris.

In the Sefer Matteh Moshe (by Rav Moshe Matt, a student of Maharshal) it is recorded that the custom is to wait to name the baby until the bris. This is reminiscent of the fact that Avram was given a new name, Avraham, at the time of his bris. In truth, the case of Avraham is totally different from ours. Avraham’s bris served the function of gerus (conversion). His neshama and personality were undergoing a major change. To use the Talmudic metaphor,

“גר שנתגייר כקטן שנולד דמי”

“a non-Jew who converts is likened unto a newly born baby.” In this case, it made sense to give Avram a new name. The new name indicated that he would have the role of “founding father” of the Jewish people. This really does not apply in the instance of a simple bris celebration. Nevertheless, the custom at every bris is to recall the giving of the name “Avraham” on the occasion of his bris.

The Talmud records an ancient custom that when bathing, dressing and putting on shoes, one always takes care of the right side of the body first, and only later the left side. The one exception is that with respect to tying one’s shoelaces, we tie the left shoe first. This discrepancy is driven by the tying of the tefillin on the arm, which is done on the left side of the body. (In the days of the Talmud, shoe straps were similar to the tefillin straps.) Why are the tefillin tied on the left arm instead of the right?

The kohanim in the Beis HaMikdash did the avoda with their right hands. Avoda done with the left hand would be deemed pasul, and would have to be done over. Rambam (Hilchos De’os 3:3) explains the theme of the pasuk “בכל דרכיך דעהו,” “know Him in all your ways,” to be that we ought not divide our activities into two areas, kodesh and chol, or into mitzva vs. secular activities, rather we should dedicate all of our activities to the service of Hashem. Even our eating and drinking, working for a living, our marriage and the raising of our children should all be done in the service of Hashem. All secular activities should be performed as a “hechsher mitzva,” as a means to enable us to lead a life of mitzvos. When we bathe, get dressed, etc., we treat all mundane activities as though we were kohanim performing the avoda in the Temple. We therefore favor the right side in all of our activities, just as avodas hakorbanos had to be done with the right hand.

Avraham Avinu had the moral and ethical conviction, as well as the courage, to put together a tiny little army to wage war against terror. Neither he nor his immediate family were personally endangered by the terrorists, yet he intuitively knew that this was the correct route to take. Firstly, because one should not sit idly by while others are suffering from terror, and secondly because ultimately, this Hitler will control so much of the globe that he will terrorize him as well. Avraham’s waging of the war was clearly an act of heroism, as was his later refusal to accept any of the captured loot for himself. Both the waging of the war and the refusing of the wealth were fulfillments of “בכל דרכיך דעהו.” Avraham truly led his whole life in a way that reflected the tzelem Elokim which he possessed. The Talmud (Chullin 89a) records a tradition that as a reward for Avraham’s refusal to accept “שרוך נעל מחוט ועד” — “neither a string nor a shoe strap,” his descendants were rewarded with the two mitzvos of the string of the tzitzis and the straps of the tefillin. When we tie our shoe straps every day, we reminisce over the heroism of Avraham Avinu. We tie the left shoe first to recall that because of Avraham Avinu’s kiddush Hashem which was articulated in terms of shoe straps, his descendants were rewarded with the mitzva of tefillin. We, too, should convert the secular sectors of our lives into hechsher mitzva, in fulfillment of “בכל דרכיך דעהו.” There will no longer be kodesh and chol; rather, the chol will become kodesh.

Rabbi Hershel Schachter joined the faculty of Yeshiva University’s Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary in 1967, at the age of 26, the youngest Rosh Yeshiva at RIETS. Since 1971, Rabbi Schachter has been Rosh Kollel in RIETS’ Marcos and Adina Katz Kollel (Institute for Advanced Research in Rabbinics) and also holds the institution’s Nathan and Vivian Fink Distinguished Professorial Chair in Talmud. In addition to his teaching duties, Rabbi Schachter lectures, writes, and serves as a world renowned decisor of Jewish law.