In Bava Metzia 17b, Mar Kashisha b. Rav Chisda speaks to Rav Ashi to question Abaye’s apparent assumption that a widow after a mere betrothal collects her ketubah. This is a diachronic sugya involving multiple actors from two countries: Second-generation Rabbi Yochanan who pronounces a rule that we don’t accept a claim that a debt has been repaid if the court established a debt and his third-generation student, Rabbi Chiya bar Abba, who questions whether this idea needed to be stated, since it was evident from a Mishnah. There is also Rabbi Yochanan saying that the idea in the Mishnah was a pearl discovered only because he had lifted the clay shard covering it; fourth-generation Abaye questioning whether this is truly a pearl, then retracting for a reason either explicitly stated or expanded upon by later generations; Mar Kashisha b. Rav Chisda objecting to sixth-generation Rav Ashi; and,finally, an anonymous revision of Abaye’s reason for retracting.

Let’s learn more about Mar Kashisha, even if only to place him within his scholastic generation. He certainly spoke to Rav Ashi, but is he a sixth-generation Amora? If his father is indeed third-generation Rav Chisda, could he have directly interacted with fourth-generation Abaye?

Mar Kashisha b. Rav Chisda often appears in the company of his brother Mar Yenuka. קַשִּׁישָׁא means lder and יָנוֹקָא means Younger. These are relative terms. Thus, in Taanit 23b, Abba Chilkiyah divides his bread and counterintuitively gives one portion to the קַשִּׁישָׁא and two portions to the יָנוֹקָא. In Ketubot 89b, Rashi writes that (the famous) Rav Chisda had two sons with identical names (presumably Mar), so as to distinguish them from one another, the older was called Mar Kashisha and the younger, Mar Yanoka. In Bava Batra 7b, Tosafot disagree, asserting that Mar Yenoka was born to Rav Chisda in his relative youth, and is thus the older brother; Mar Kashisha was born to Rav Chisda in his old age. (Perhaps “Mar” is then not their name, but a title.)

Chronological Constraints

In Toledot Tannaim vaAmoraim, Rav Aharon Hyman questions this Tosafot. After all, according to the Epistle of Rav Sherira Gaon 3:3, Rav Chisda1 died about 309 CE, while Rav Ashi died about 427 CE, which is 118 years after Rav Chisda. Rav Chisda lived about 92 years. If Mar Yanoka was born in Rav Chisda’s youth, how could he exist in Rav Ashi’s yeshiva about 200 years later? He also explains Tosafot’s motivation for making Mar Yanoka older—when the two are listed, Mar Yanoka always precedes Mar Kashisha.

Rav Hyman also would have been inclined to say that these aren’t the sons of the famous Rav Chisda. This would solve the chronological problem of the 200-year time span. However, since there’s no other plain Rav Chisda, Rav Hyman concludes that both sons were born to Rav Chisda in his old age, close to his death. That’s why we never see them talking to their father or citing a halacha in his name.

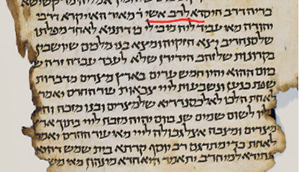

I would disagree with Rav Hyman here. Even if these sons were born to Rav Chisda in his old age, it’s difficult having a fourth-generation Amora regularly conversing only with a sixth-generation Amora, Rav Ashi. Mar Kashisha b. Rav Chisda appears about 18 times in the Talmud, always speaking to Rav Ashi. The one exception is in Menachot 109b, where he speaks to fourth-generation Abaye, but Rav Hyman notes in Dikdukei Soferim that it should read “to Rav Ashi.” Indeed, the Columbia: X893IN Z64 fragment has “to Rav Ashi” instead of “to Abaye.”

Further, who cares that there’s only one plain Rav Chisda? I suppose Rav Hyman is influenced by the title “Rav,, as opposed to just the unadorned Chisda who could be anyone. Still, a patronymic (B ben C) serves to distinguish one Amora from another with the same name (another B). But, when providing a patronymic for A, must we list his grandfather (A ben B ben C) if B isn’t the famous one? There’s a Mar Kashisha son of Rava, so mentioning “son of Rav Chisda” will distinguish A from another A. Even Rav Hyman doesn’t consistently claim that we assume that without the grandfather’s patronymic, it must be the famous one. For instance, he isn’t convinced that third-generation Rav Pappa bar Shmuel is the famous Shmuel’s son.

We’d have to find another Rav Chisda, and one that isn’t a scribal error. Candidates include: Rav Chisda bar Avdimi in Berachot 33b (though he might be Rav Yitzchak bar Avdimi); Rav Chisda bar Avira (though he’s almost certainly Rabbi Chasida citing Rabbi Zeira); Rav Chisda of Justinia in Zevachim 112a (according to Dikdukei Soferim and Munich 95; we have Rav Chiya of Justinia); and the fifth-generation Israeli Amora, Rabbi Chisda. This last candidate is perfect as father of contemporaries to Babylonian sixth-generation Rav Ashi.

Relating to Rav Ashi

Rav Hyman, expanding on his theory, notes that Rav Ashi presided as rosh yeshiva for close to 60 years. Therefore, it’s a possibility that Mar Kashisha and Mar Yanoka sat before Rav Ashi at the beginning of his tenure, in 371 CE. At that point, they’d be slightly older than 60 years old. Though Rav Ashi would be much younger than them, since he was the rosh yeshiva, all the elders of the generation would sit before him. Still, those two wouldn’t sit before him as students. Rav Hyman points to many interactions demonstrating this collegial, rather than teacher-student relationship. For instance, in Pesachim 107a, the two brothers tell Rav Ashi how when fifth- and sixth-generation Ameimar visited them, they didn’t have wine for Havdalah, and Ameimar’s resulting conduct. In Bava Metzia 66b, they tell Rav Ashi what the Nehardeans say in Rav Nachman’s name. In Bava Batra 7b, they say to Rav Ashi that the Nehardeans are consistent2. Rav Hyman believes Mar Yenoka died earlier than his brother, which is why we sometimes see only Mar Kashisha interact with Rav Ashi.

I’d point to a fascinating exchange in Bava Kamma 96b. Mar Kashisha b. Rav Chisda cites Rabbi Yochanan that even an automatic intrinsic change in the possession of a thief, e.g. a thief stole a lamb and it became a ram, becomes the thief’s acquisition. Thus, if he subsequently slaughtered it, the robber doesn’t incur a fourfold fine, because he’s slaughtered his own animal. The problem with this attribution is that in Bava Kamma 65b, it is the Amora, Rabbi Ila’a, who says this, arguing with Rabbi Chanina. Rav Ashi chastises Mar Kashisha: “Haven’t I told you not to exchange names? This was stated in Rabbi Illa’a’s name!” Attribution is important, for perhaps Rabbi Yochanan agrees with Rabbi Chanina. Perhaps then we should regard other citations by Mar Kashisha as untrustworthy—Rav Ashi has told him this in the past. Regardless, this might indicate more of a teacher-student relationship.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.

1 He writes 620 to minyan shtarot, which begins 313 CE. And there is no year zero. Hebrew Wikipedia writes 390 CE. Rav Ashi with 738 to minyan shtarot.

2 Tangentially, “Nehardeans’ ‘ refers to fifth-generation Rav Chama, who presided over Nehardea academy while Rav Nachman bar Yizchak presided over Pumbedita. Rav Chama was referenced immediately above in the sugya. This is the likely source for Sanhedrin 17b mapping the plural אמוראי דנהרדעי to Rav Chama. But the sugya continues with Rav Nachman citing Shmuel, two other Nehardeans, with the point being that all these Nehardeans are consistent.