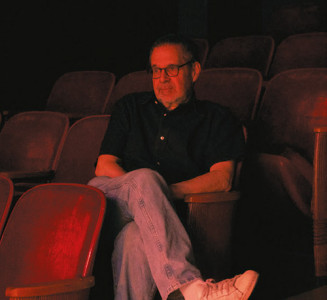

Marc Weiner is a disabilities attorney and a highly skilled playwright. When I interview him, his approach to the subject of Hidden, his recent off-Broadway production, is direct, factual, artistic, and emotional. When I ask Weiner why he chose a narrative about children hidden as Catholics during the Shoah, he recalls graphic images of children behind gates, with ragged clothes, wearing Jewish stars, and adds, “I think it’s about the children,” and his emotional connection to his daughter.

Hidden deals with Jacob Epstein’s decades-long search for and discovery of his brother’s children, who, during Nazi-ruled Warsaw, he places with their non-Jewish nanny. The children are then left with nuns, and subsequently, with Polish Catholics who raise them as their own. Much of the script deals with the consequences of this discovery, and sensitive, unanswerable Holocaust-related questions.

“I Write Because There are Certain Things I Can’t Do.”

Weiner can’t change the past or take direct action against Nazis, but he can dramatize what happened in the hope that it will make a statement. His desire to raise awareness of the Church’s role in sheltering Jewish children during WWII has piqued. Since 2009, Weiner has collected research data. He contacted the ADL’s Hidden Children Foundation, read voraciously, including books by renowned author/psychologist/filmmaker Eva Fogelman, and conducted phone interviews with “four or five men,” 70-80-year-old former hidden children. He felt like he was walking on eggshells during the interviews.

Weiner refers to the custody battle between former ADL director Abe Foxman’s parents and the nanny who hid him. He also recounts how post-war, one of his hidden interviewees discovered that he and his mother had hidden in the same building, unbeknownst to either. These survivors both had options to reconnect with their families that others didn’t. Weiner’s data supports this.

Weiner Identifies Where Church Policy and the Church Hierarchy Impeded Family Unity

Weiner notes the Church’s position that a Jew who is baptized is no longer Jewish. He cites Daniel Jonah Goldhagen’s (2005) article (https://www.beliefnet.com/faiths/2005/01/the-churchs-kidnapping-policy.aspx). Goldhagen criticizes a secret, Vatican-approved 1946 directive that baptized Jewish children should not be returned to their parents. A National Public Radio podcast contains the text of the directive (https://www.npr.org/2005/01/21/4461958/document-renews-debate-on-vatican-role-in-wwii). In Hidden, Jacob argues,” The Church cannot erase a Hebrew name with water and a few words.”

Weiner mentions another initiative—one to baptize adult Jews, which contrasts with the baptism of children in monasteries and convents. Monsignor Angelo Roncalli (later Pope John XXIII), met in Turkey with Ira Hirschmann, War Refugee Board and later UNRRA representative. Their plan was to provide at least 24,000 Hungarian Jews with baptismal certificates to avoid deportation. According to records, the baptism/sacrament part was voluntary and non-binding.) (See also https://www.yadvashem.org/odot_pdf/Microsoft%20Word%20-%206413.pdf).

This outcome differed for vulnerable Jewish children, who existed at the discretion of other actors. Abraham Foxman (NPR, 2005) now believes that his Polish Catholic nanny’s insistence on keeping him was directed by her priest, and the Vatican.

“The Line Between Good and Evil Never Stands Still”—Marc Weiner

Weiner initially wanted to strike out at the Church because of what they failed to do. He refrained because he didn’t want the play to be black and white; good and evil were often gray then. Nevertheless, hiding Jews within the Church is highly controversial, and sparks emotional reactions, as sometimes happens during performances, when audiences have reacted strongly to Hidden’s characters, who face profound ethical and religious dilemmas.

A brief synopsis: After witnessing his brother and sister-in-law murdered by the Nazis in the ghetto, Jacob Epstein entrusts their nanny Petra with hiding the three children. She brings them to a convent, but they can’t stay because Benjamin, the toddler, is very ill and contagious. The nuns fear an epidemic, but also, as some boys have discovered that Joshua, the eldest, is Jewish, the whole convent could be at risk.

When Dr. Victor Reszki, a Polish Catholic, examines Benjamin, he knows that he cannot bring a mortally ill Jewish child to the hospital. He does the “merciful” thing, and pretends that Joshua and Hannah Epstein, now Joseph and Nina, are his brother’s children. He raises them as Catholics. When Jacob searches for them after liberation, Victor refuses to return them. It’s only through providence-hashgacha pratis- that decades later, Jacob discovers his niece Nina/Hanna, whom his son David rescues during a student demonstration at Columbia University. So begins an irreversible, domino-like chain of events affecting every character, including Joseph, who has joined the priesthood and is being deployed as a chaplain to Vietnam.

Joseph/Joshua does remember being Jewish, going to shul and standing on the bima with his father. He has kept wrapped and hidden spoons, engraved with a Magen David and the siblings’ date of birth, so that they would remember being Jewish.

When wounds closed for 25 years are finally re-opened, those affected are bound to be riddled with trauma, anger, guilt, and unanswered questions. Through each of his characters, Weiner’s questions about the impact of guilt and culpability drive the play.

Weiner describes the reactions of audience members after early readings and live performances. In the latter, two women expressed opposing views of Jacob’s behaviors. Is he to blame for leaving the children with a nanny who, out of fear, or hunger, turns them over to nuns for safekeeping? Why did he wait five years before coming for them? Why did Victor not return Nina and Joseph to Yaakov, their closest living relative? When Jacob returns to reclaim the children, Victor has had them for five years, so from his perspective, why should he give them up? Weiner proposes that a nanny who hid a Jewish child for a few years would have felt the same way. And what of a child’s perspective? Joseph/Joshua tells Jacob how he waited and waited for someone from his family to come and take him from the Reszkis, but no one came. So what he knows, and is his reality, is as a Catholic priest with a calling.

After one reading, two audience groups presented conflicting views of the characters’ actions. At one performance, Eva Fogelman approached Weiner. She suggested that he increase Jacob’s dialogue to explain to Joseph and Nina why he didn’t come back for five years “because he was in Treblinka or running for his life at the time,” and that he didn’t abandon the children.

While researching hidden children, Weiner read about Orthodox parents who refused to leave their children with the Church; they perished. “So, what was the choice?” he asks. As for the hidden children, the pintele Yid, that spark in a soul, may be obscured, but it is not obliterated.

All Is Not Lost

In post-Holocaust aftershocks, hidden children may experience guilt, angst, and confusion, as do survivors of ghettos and camps, but from different vantage points. For some, the shocks of disclosure may elicit a positive view of their past. Joseph/Joshua is glad that Jacob has found them. He writes to Jacob from Vietnam and tells him that he has brought his Magen David spoon with him. Nina/Hannah brings her baby son to synagogue and together with her uncle, aunt, and David, says Kaddish for her parents. And then there are those who finally acknowledge their Judaism on their deathbeds. We all hope for “Never Again,” but also for “Never Too Late.”

Rachel Kovacs is an Adjunct Associate Professor of communication at CUNY, a PR professional, theater reviewer for offoffonline.com—and a Judaics teacher. She trained in performance at Brandeis and Manchester Universities, Sharon Playhouse, and the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. She can be reached at [email protected].