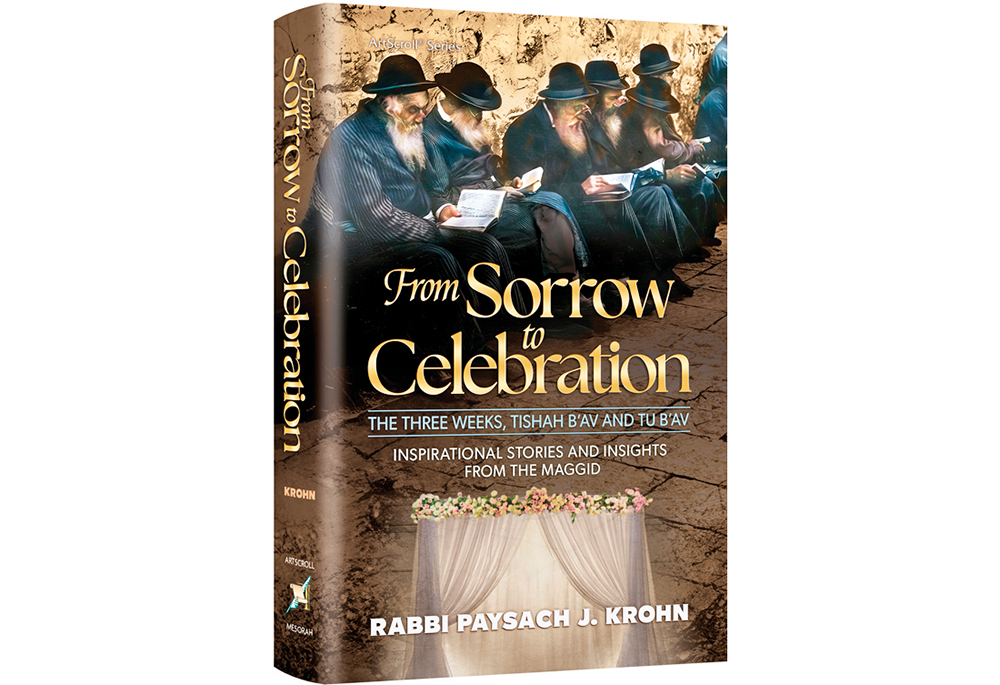

Excerpting: “From Sorrow to Celebration” by Rabbi Paysach Krohn. Mesorah Publications Ltd. 2024. Hardcover. 600 pages. ISBN-13: 978-1422641118.

(Courtesy of Artscroll) Since the history of the first Jewish family, that of Avraham Avinu and Yitzchak Avinu, we have been ingrained with unconditional loyalty to Hashem, even at the expense of our own lives.

Martyrdom for Hashem became embedded in the Jewish character when Yitzchak Avinu urged his father Avraham to tie him to the altar so that he could be sacrificed in accordance with Hashem’s command.

David HaMelech writes, Ki alecha haragnu kol hayom — Because for Your sake we are killed all the time (Tehillim 44:23). In the Gemara we are permitted to learn on Tishah B’Av, Chazal (Gittin 57b) give numerous examples of Jewish martyrdom. They first cite the heartbreaking story of Chanah and her seven sons who refused to worship an idol at the command of the Syrian-Greek Antiochus, some two hundred years before the destruction of the Second Beis HaMikdash. Each of her seven sons cited a different pasuk for refusing to worship the idol, and each was brutally murdered.

After her seventh son was killed, Chanah said, “My sons, go and tell Avraham, your forefather, ‘You bound one son [Yitzchak] on an altar [in order to sanctify Hashem’s Name]; I bound seven [sons] on altars [and they all gave their lives to sanctify Hashem’s Name].’”

Rav Elazar Menachem Mann Shach wonders about the purpose of her words. Surely such a righteous woman would not be boasting of her superiority to the holy Patriarch of our people! What, then, was her intent?

He explains that Chanah was certainly not comparing herself to Avraham. On the contrary, she was denying herself the credit for her heroism and that of her children. She was giving credit to Avraham. Her words, far from being boastful, reflected a profound understanding of the source of our nation’s spiritual strength. “Look what you have done for your people!” she was saying to Avraham with gratitude and awe. “Where did I find the courage and strength to sacrifice my seven sons? It was from you. You bound only one son on the altar, yet through that great, pioneering act of devotion and faith, you forever empowered your descendants to make even greater sacrifices to sanctify Hashem’s Name, such as I have just done with my seven sons.”

The Gemara there cites more subtle understandings of the above verse in Tehillim.

Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi says the pasuk refers to the mitzvah of bris milah. Perhaps because there is some loss of blood during every circumcision, and the pasuk states, ki hadam hu hanefesh — For the soul of the flesh is in the blood (Devarim 12:23; see also Vayikra 17:11), the act of the bris is thus considered a form of mesirus nefesh.

The following story depicts incredible mesirus nefesh in performing the mitzvah of bris milah.

The Bluzhever Rebbe, Rav Yisroel Spira (1889-1989), would often retell an event he witnessed in the Janowska concentration camp.

A group of Jewish men and women were being forced down from an overcrowded train and marched toward a barracks. Nazi soldiers stood by watching sternly as the broken Jews walked past. Suddenly a woman approached a soldier and said firmly, “Give me that knife,” motioning to his bayonet.

The Nazi was only too happy to oblige, as he thought the woman wanted to kill herself. The Rebbe saw the bayonet in the woman’s hand and cried out, “My dear daughter, don’t do it! One never knows when salvation will come. Put the knife away!”

“Rebbe,” the woman answered, “I’m not about to do anything to myself.” She opened the bundle she was carrying and drew out her baby. To the Rebbe’s utter amazement, she recited the berachah of bris milah, and she then circumcised her child. She then cried aloud, “Ribbono shel Olam, You gave me a healthy child; now I am returning him to You as a kosher Jew!”

That night both mother and child perished al Kiddush Hashem.

After the war, the Rebbe, with a broken heart, would often tell this story of commitment when he attended a bris.

________________________________

A second story regarding bris milah was told to me by the Maggid of Yerushalayim, Rav Sholom Schwadron, who heard it from the Kaliver Rebbe, Rav Menachem Mendel Taub (1923-2019).

In the 1970s, when the Soviet Union was under strict Communist rule, it was forbidden to perform a bris. The punishment for having a son circumcised was immediate firing from work, with the possibility of criminal charges, trials, and perhaps even a jail sentence. For this reason, the great majority of Jewish boys born in the Soviet Union during those years remained uncircumcised.

Nevertheless, some Jews took the risk of gathering a few highly trusted friends and having the bris performed clandestinely. Although a bris should be performed on the eighth day of a child’s life, many times parents had to wait three weeks, three months, or even six months before they could arrange the risky mitzvah.

For the first few weeks after the birth of a son, parents could almost feel the presence of the authorities, and no hint of a bris could even be mentioned. The family watched not only for officials, but for “friends” who might actually be informers.

In the town of Kirov* along the Vyatka River, there was a “trusted minyan” of people whom the Schleider* family wished to invite to their son’s bris. They were all discreet, dependable, and responsible people. They would never betray a family and no police authority could obtain any information from them. Often, it was one of these men who advised the family when it was “safe” to have the bris.

The Schleider baby was almost a year old, but he had not yet been circumcised. After a long wait, the atmosphere became a bit less tense and the Schleiders were informed that it was safe to have the bris. The mohel was called, the guests gathered in a basement, and the child was brought in.

The bris was performed, the blessings were recited, and they all wished each other mazal tov. The baby was brought back to the room where his mother was waiting for him. Suddenly there was a piercing scream, a wail, and a cry. There was a loud thud. People ran to the room and were shocked to see that the mother had fainted. After they revived her, she explained.

The young mother had feared that her son might never have a bris, that she would be lulled into negligence because of her fear of the authorities, that she might capitulate to fear and never have her baby circumcised. She was determined not to let that happen and she made a vow that would compel her to long for the bris, so it would be paramount in her mind at all times. She vowed not to kiss her son until he had had his bris.

For close to a year, she suffered the pent-up emotions that only a mother can feel. Finally, after the bris, she took her son into her loving arms and kissed him fervently.

Overcome with emotion, she fainted.

Perhaps, then, the pasuk of Ki alecha haragnu kol hayom — Because for Your sake we are killed all the time, can be understood homiletically: This courageous woman, who deprived herself of the pleasure and delight of kissing her baby for so many months, despite feeding him, holding him, and dressing him, was “killing herself” just for the sake of the mitzvah of bris milah.

*Names were changed

Reprinted with permission from the copyright holder, ArtScroll Mesorah Publications.