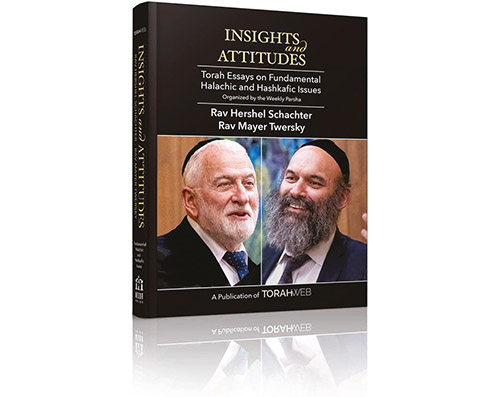

Editor’s note: This series is reprinted with permission from “Insights & Attitudes: Torah Essays on Fundamental Halachic and Hashkafic Issues,” a publication of TorahWeb.org. The book contains multiple articles, organized by parsha, by Rabbi Hershel Schachter and Rabbi Mayer Twersky.

In the order of the Mishnayos, Maseches Sota follows Maseches Nazir. The Talmud (Nazir 2a) explains that this is based on the pesukim in Parshas Naso, where the parshiyos of nazir and sota are next to each other. The reason for the juxtaposition is explained by the Talmud as follows: normally the Torah does not want us to be extreme. The middos are referred to as such because each must be implemented with the proper measure. (The Hebrew word “midda” means a measure.) One who accepts upon himself to become a nazir, i.e., to become, in a certain sense, an ascetic, and to totally abstain from wine, is considered a sinner (see Ta’anis 11a). However, once in a while we consider a nazir to be a kadosh, a holy person. One who lives in a generation (like ours) where there is much corruption and peritzus (lawlessness), and one who witnesses a sota, must be concerned that he too may follow the path of the corrupt society. Under such circumstances, the Torah recommends that we take extreme measures to offset the improper influence of society.

The Rambam is famous for his presentation of this idea in Hilchos De’os 2:2. One of the modern Jewish thinkers has attacked the Rambam for having picked up this concept from the Greek philosophers and presenting it in Mishneh Torah as though it had a source in Talmudic literature. But the truth is that it is rooted in the rabbinic comment regarding the juxtaposition of the two parshiyos of nazir and sota.

We live in a generation of instant communication. Everyone around the world is notified immediately about all the ganavim (thieves) and all the sotos anywhere in the world. We do not just see one sota, rather we are made aware of many sotos. Although under normal conditions it would not be healthy to follow an extreme path in life, in our circumstances extreme measures are recommended.

This recommendation is true not only in the area of בין אדם למקום, but also in the area of בין אדם לחבירו. We are surrounded by many who cheat in business, cheat on income tax, sales tax, etc. We should be careful not only to be honest and follow the law, but even bend over backwards to make sure that we don’t follow these extremely improper practices of our society. The Talmud (Avoda Zara 40a) describes kosher fish as having a backbone, and having the ability to swim upstream, i.e., against the current. Jews must always develop such a backbone and see to it that they swim against the current.

The Rambam interprets the Mishna in Pirkei Avos (4:4) as recommending yet another exception to the golden mean. The Tanna Rabbi Levitas of Yavne used to say that one should always be “very very” humble. The Rambam (Hilchos De’os 2:3) interprets the repetition of the term “very” to imply that one ought not to follow the golden mean with respect to arrogance and humility, but should rather go to an extreme in adopting the quality of humility.

The Rambam explains that biblically, humility and arrogance should be the same as any other middos and one should attempt to follow the middle path, but just as the Rabbis introduced so many gezeiros (decrees) and harchokos (distances) in the area of בין אדם למקום and בין אדם לחבירו, so too here did they introduce a gezeira in this area of בין אדם לעצמו. The Rabbis were concerned that many people, or perhaps most people, would not be able to determine where the midpoint is between arrogance and humility, and would most probably err on the side of arrogance. Therefore, the Rabbis made a gezeira derabbanan (rabbinic decree) that we must all go to the extreme regarding humility.

Rabbi Hershel Schachter joined the faculty of Yeshiva University’s Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary in 1967, at the age of 26, the youngest Rosh Yeshiva at RIETS. Since 1971, Rabbi Schachter has been Rosh Kollel in RIETS’ Marcos and Adina Katz Kollel (Institute for Advanced Research in Rabbinics) and also holds the institution’s Nathan and Vivian Fink Distinguished Professorial Chair in Talmud. In addition to his teaching duties, Rabbi Schachter lectures, writes, and serves as a world renowned decisor of Jewish Law.