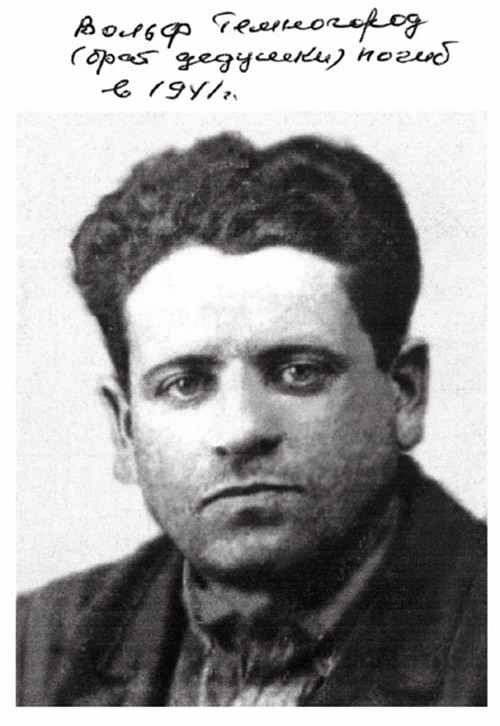

Military records indicate that Wolf (aka Velvel) Alterovich Temnogorod was born in 1899 in Starokonstantinov, Ukraine. Velvel, my granduncle, married in 1927 in Vinnitsa, Ukraine. He was the father of two daughters.

His descendants informed me that one of the martyrs of Babi Yar may have been Velvel. That massacre took place near Kyiv, Ukraine, in 1941 when Velvel was in the prime of his life. Whether it was at Babi Yar or elsewhere in Kyiv, nobody knows. His descendants told me that “it is said that the neighbors betrayed him to the Nazis. Where he was killed is not known.”

Born in 1899, Velvel was of bar mitzvah age when my grandmother emigrated. Our family memorabilia include four letters he penned to my grandmother, his sister, 16 years his senior. That was after she left her homeland to join my grandfather in America. My grandmother traveled steerage on the Potsdam vessel in 1912 with my toddler uncle and infant father.

My aunt, fortunately, saved dozens of handwritten, treasured letters from members of all our family branches. Following my aunt’s death in 1993, my brother Al and I came upon the browning pages while completing the daunting task of emptying our aunt’s apartment. Soon after, with our children in tow, my husband and I took a trip to California to hand-deliver the precious batch of correspondence for translation by my cousin in Los Angeles.

In the letters penned on behalf of my illiterate great-grandfather, a tool sharpener, to send to his daughter in America, Velvel wrote the details of daily life in Chudnov. The letters, written in Yiddish, shared hints of joy and words of encouragement, such as, “…we are happy to hear that you are able to teach [your children] Yiddishkeit.” The prose, more often, piercingly echoed with heartache and sorrow.

Eventually, Velvel broke the news of their father’s passing with the painful words, “Our father is dead six years already.” Parenthetically, he added the yahrzeit date of my great-grandfather’s death, 21 Iyar, 1916.

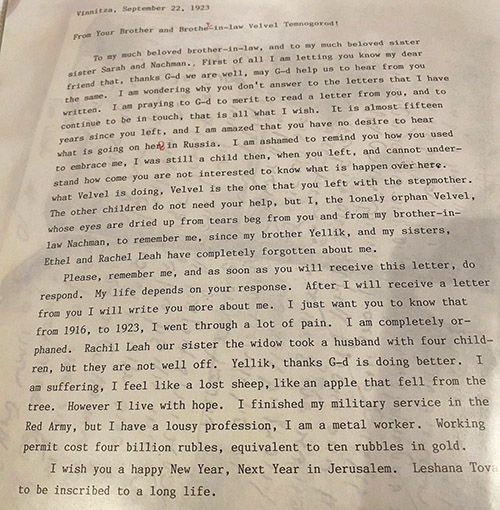

In a letter dated September 22, 1923, Velvel surprisingly added to his New Year greetings, “Next Year in Jerusalem.” Backtracking, in a letter dated the summer of 1922, Velvel reported, “In 1919, I was recruited into the Red Army and was in service till 1922, I was released May 1, 1922 … I do plan to emigrate to Eretz Israel, maybe this winter.” His ardent desire to relocate to the Holy Land was a dream several direct descendants realized.

In the letters written in those early years of the 1920s, making a case for help due to their severe poverty, Velvel implored, “If you want to send something, do not send money, only a package.” A similar sentiment in a follow-up letter reads, “I want you to know that I received your two dollars, but please, do not send money anymore, send rather a package, clothing is in short supply here.”

With the coveted letters painstakingly translated and typewritten versions in English returned to me by my cousin Harry Langsam, z”l, I spent years finding and friending as many of the descendants of my grandaunts and granduncles as possible. Many of our relatives perished on the battlefields at war or mercilessly in the shtetl. Yet, at least one descendant survived from each of the 11 siblings of my grandparents. Since my grandparents were first cousins before marriage, the others were all from the same large contingent of cousins.

After locating Velvel’s daughter Rosa living in Israel and making a long-distance call to her, Cousin Rosa’s granddaughter, a young girl at the time, spoke English, and she translated our emotional conversation. We all shed tears that day.

It was not long before an envelope arrived with pictures of Velvel. As I hastily but carefully viewed the photos sent by Rosa from Israel, my first thought was, “Wow, what a family resemblance.” In the accompanying letter, Rosa wrote that the very last time she saw her father was in June 1941. Rosa made aliyah in 1990 with her younger daughter and that daughter’s family. Rosa’s elder daughter immigrated to the United States in 1979.

Our daughter Rina extended her stay in the Holy Land during a Birthright trip to Israel in 2011. While there, she spent quality time with Velvel’s granddaughter, son-in-law and two daughters. Velvel’s great-granddaughter, Gili, hosted Rina, as did other relatives we would never have known had my aunt not saved those antiquated but all-telling letters.

Since Rina’s visit, Gili and her sister each married their bashert, and Gili has a young son. Velvel’s grandson from his younger daughter corresponds with me as well. He lives in Germany with his wife, two children and three grandchildren.

Over the years, I transferred the letters, which my aunt secured in a cookie tin and stored at the bottom of her food pantry, into archival sleeves and neatly filed them in a hefty white notebook. To this day, I steadfastly continue to accumulate notes, constantly adding the information to my family records. All along, I hoped that as the years went by, there would be more to add to the story.

My dreams came to fruition in 2021 with the discovery of the Temnogorod family line on revision lists. Those census records helped fill in the information on our family tree dating back to the mid-1700s. That accomplishment took help from strangers from Chudnov, the shtetl of my ancestry, fellow researchers, cousins all over the world who speak the language, and a little luck.

To my family and me, that enlightening information is priceless. It also is an essential aspect of the history of families from Eastern Europe.

Temnogorod, meaning “dark city,” to say the least, is a very uncommon family name. Before emigrating from Ukraine in 1997, my cousins searched long and hard through directories for others with the same name, to no avail. That knowledge underscores that we found the correct clan.

Given that first names in our family continued in usage throughout the generations, in memory of deceased forbearers, the chain remains unbroken. By combining information from the correspondence that my aunt saved with names carried down throughout the generations of our family, we were able to prove our heritage and bring life to our family members.

In a letter dated February 14, 1913, Velvel wrote, for example, “… and if you intend to send me a Purim gift, please, send me a little Torah scroll.”

My mantra is that everyone deserves a legacy. I am somewhat relieved that Velvel did not die in vain and that his family is still growing and prospering.

As his life passed before him, while innocently standing at Bari Yar, or elsewhere in Kyiv, did my Granduncle Wolf (aka Velvel) Temnogorod have time to say the Shema, or am I saying it for him now? שְׁמַע יִשְׂרָאֵל יְהוָה אֱלֹהֵינוּ יְהוָה אֶחָֽד

Sharon Mark Cohen, MPA, is a seasoned genealogist and journalist. A staff writer at The Jewish Link, Sharon is a people person and born storyteller who feels that everyone deserves a legacy. Follow her Tuesday blog posts at www.sharonmarkcohen.com.