One of the most important symbols of Judaism representing one’s cerebral and physical commitment to Judaism and Jewish practice is the tefillin. These leather boxes containing various significant biblical passages are bound to one’s arms and one’s head. Inaccurately translated as phylacteries, they are not amulets but physical reminders of one’s fidelity to Judaism and Jewish practice. The attachment to these ritual objects is quite powerful since they are worn for life after the age of 13. My older brother has our late father’s tefillin, and I wear my uncle’s, which are over 120 years old. The ink is turning red but I am assured that they are still kosher.

Our family recently celebrated the occasion of our youngest grandson putting on tefillin in preparation for his upcoming bar mitzvah. I am a firm believer that people should understand the mitzvot that they observe, especially those that they do on a regular basis. Why this is not covered in yeshivas and day schools is the subject of another column. My wife and I are blessed with six grandsons among our grandchildren and I have taken upon myself the obligation to provide each one with their tefillin. Some people visit the tefillin factory in Israel to educate their sons/grandsons about the mitzvah of tefillin. Others visit a sofer or a Judaica store to purchase their tefillin, which come in a variety of kosher gradations and hiddur. Boys all learn how to put on tefillin. I wanted my grandsons to understand this mitzvah on a deeper level. The symbolism of the shel yad and shel rosh, how tefillin are made, which parshiot are in the tefillin and why, as well as the different variations and traditions associated with this fundamental mitzvah.

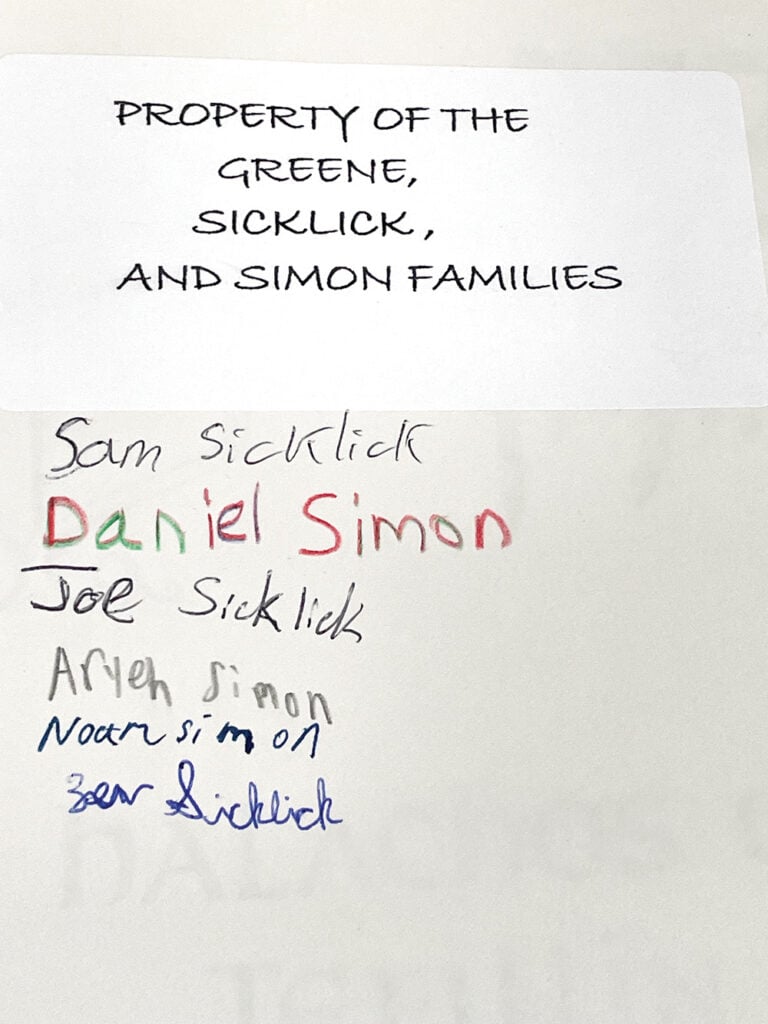

I started by giving them the classic book on tefillin by Rabbi Shimon Eider. Each boy signed his name in the book and gave it in turn to the next in line. This book, if it is still in print, provides a complete guide to the mitzvah of tefillin, how they are made, how to treat them, how to wear them, what they represent. complete with illustrations. I then met with the sofer, Rabbi Abraham Teicher in Teaneck, to select the parshiot, script style, size, and to discuss the type of knots that I wanted for the tefillin. Each of these items can vary greatly, which also affects the ultimate pricing of the tefillin. This meeting is crucial since it sets the standard for all six pairs of tefillin that I purchased over the years.

As we approach the time for the bar mitzvah, each grandson meets with Rabbi Teicher. At this meeting he shows the boys how tefillin are made, lets them handle rawhide molds of the batim, parchment, quills, and even the recipe for making the ink. The mitzvah is explained in detail. Once the basics are covered the sofer gets to work assembling the tefillin and getting the parshiot ready. A second meeting is scheduled in which the individually made tefillin boxes are presented. Then the parshiot are checked in case there are any missing letters or words. The sofer reads from the parchment while my grandson follows along in a tikkun to check each word. This is done for each of the four parchment inserts for the shel rosh and the big one for the shel yad. As each parsha is checked the sofer ties it up with special fibers and inserts it into the tefillin box. When all the parshiot are checked and inserted we make the final appointment.

The sofer sews up the tefillin boxes with special giddin (sinews) and at the final meeting sizes the shel rosh and shows the young man how to wear the tefillin, how to wrap it up after davening, and most importantly, how to take care of the tefillin. In between all the learning there is much humorous banter and the sofer tells of the horror stories of boys who didn’t take care of their tefillin.

I have my preferred tefillin style and type of knots. If at some time any of my grandsons wish to change or adopt a specific hiddur—wonderful. This was not an inexpensive project but it was worth every penny to make sure they understood what they would be doing for the rest of their lives. Doing mitzvot by rote without understanding them has value but nowhere near the level of doing them with comprehension and knowledge. That should be the goal of every teacher and every parent (and indeed every Jew).

Rabbi Dr. Greene is the principal at Yeshiva Keren HaTorah of Passaic-Clifton.