(Continued from previous week)

So, what did big shot Norbert do? I started dragging/carrying the bags from the pyramid away from underneath the hole so that more could be dropped down. You know, an 80-pound bag for a healthy teenager is no big deal, but after having dragged/lifted 50 of them, 80 pounds had become a big deal. And it wasn’t the end yet. I never realized how big a railroad car is, meaning how many 80-pound bags it could hold. Hundreds if I remember correctly.

After a while I called a hold to the deliverymen above—I wanted to see how much more there was on the truck. To my surprise (read “dismay”) the truck was still about half full. So back down I went to continue my slave labor until the job was done. At the end I could hardly drag myself upstairs to sign off on the shipment. But when later my father came and saw me sitting there exhausted, and then looked at what I had done, his expression of amazement and pride in my accomplishment made me forget all my aching muscles.

Although I had gotten to like working in an office setting, I found that I also enjoyed working physically, and not just working, but working hard and fast.

Then and there I learned that when a job is being done in a certain way for a long time, and done for no other reason except that it had always been done that way, it is time to look for a change, or at least time for a re-evaluation. Partially because of these differences with Opa, but mostly because I did not see much of a future for myself in the hides and skins business, I decided not to continue working for Opa when I graduated from college.

Reflections (written 2018)

As I finish reviewing a chapter in my life, my schooling, and before starting a new chapter, my working career, I want to reflect on what school meant to me then, and what it means to me now looking back almost 70 years later.

Going to Stuyvesant High School is now only a haze in my memory. There is little that I recall now except it was always a rush. A rush to go to early-morning classes, a rush to go from class to class with very short gaps in between, a rush to go to work after school at my father’s warehouse, a rush to get the work done as quickly as possible, a rush to get home, a rush to do homework and get ready for the next day of rush, rush, rush.

I am looking at the “Stuyvesant Indicator 1944,” the graduation yearbook, in order to refresh my memory. There were 11 classes of about 45 students each, which is about 500 in total. Since there was a morning and an afternoon session it means that each session had about 250 students.

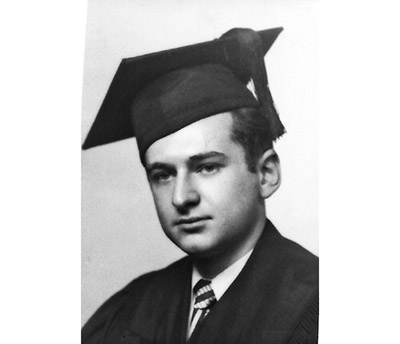

According to this book at least, I was not a bad-looking boy, certainly with a lot more hair than now. Since every student picture has shown next to it the clubs the student belonged to, the profession they were aiming for and the college they were going to attend, my description is outstanding—for its brevity! Some students listed 8-10 clubs plus college and profession—mine was “Scholarship Pin.” Frankly I don’t remember getting a pin, or telling anyone to list it.

What does that tell you? I did not belong to any clubs. Which meant I did not socialize in high school. Why? I worked, and worked, and worked any free time I had.

Did I miss socializing? I don’t think so. You can’t miss something that you are not even aware of.

Now let’s look at college. I am now looking at the “Lexicon 1949,” the yearbook of “The School of Business and Civic Administration of the City College of the College of the City of New York” as it was called then. Quite a mouthful.

Still a good-looking boy, lots of hair. But surprise, or rather no surprise. Against mostly multiple entries of clubs in addition to the degree and major, mine just says “BBA- Foreign Trade-Foreign Trade Society.” Very interesting, since I do not recall ever attending a single meeting. Maybe the editors just felt sorry for all that blank space.

What do I recall about the years in college? If I look at today’s college students, how they dress, how they behave—it was different then. Of all the classes that I took, I remember only one distinctly—because it was so different. There were only about 10 students in the class on economic geography and the professor gave the class in his home living room on the carpeted floor somewhere on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. Maybe I remember it so well because I received a straight A’s.

Now, dear reader, you can look above and read the sentence about missing socializing. The same applies here for college.

So, after reflecting in 2018 what school had meant to me so many years earlier, let us go back to see what those years of schooling had done for me.

(To be continued next week)

By Norbert Strauss