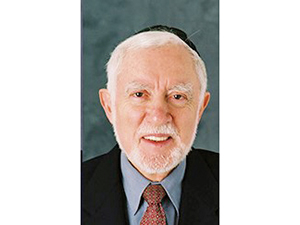

This weekend marks the shloshim of Rabbi Avraham Holtz, z”l. While best known as a world-renowned expert on Shai Agnon, as well as one of the foremost resources on the Hebrew language, for me, he, along with his family, was my primary teacher on what it means to be a committed Jew today. And while he had many beloved students as a professor at JTS, I had the privilege of knowing him as a personal teacher.

I met Rabbi Holtz’ son Shalom as a freshman at Harvard, when I was just beginning to understand how little I knew about Judaism. That year, Shalom invited me to his home in Queens for the seders and I was introduced to a world both steeped in tradition and inspired by the renaissance of the Jewish people in Eretz Yisrael. Allow me to share with you some of what I learned.

Like many great scholars, Rabbi Holtz best taught as a storyteller. My favorite story involved a description of a ketubah he found in the seminary archives from the town of אויווינגטאן. After several minutes, he was able to decipher the place of the wedding— Irvington, New Jersey! The ketubah had preserved the classic Jewish pronunciation of this city, not simply transcribing the official name.

This anecdote goes to the core of Rabbi Holtz — his dedication to preserving Jewish tradition through his love of the language of the Jews. In Agnon, he found the writer par excellence dedicated to this task, with his commitment to both the Hebrew language and incorporating traditional Jewish texts in his oeuvre. Every time I hear a ketubah read under the chuppah, I think of Rabbi Holtz’s love for our language — and our responsibility to remain committed to it.

Another story, one that Rabbi Holtz published himself. Rabbi Holtz was an early champion of the Israeli author Aharon Appelfeld, who was not well known in America for many years. After Appelfeld’s work was eventually glowingly reviewed in the New York Times, the chancellor of JTS told him, “Holtz, you picked a winner!” Rabbi Holtz’s reply — which is even more true today than 40 years ago — was “Would you need to wait for the acclaim of the New York Times for you to determine who is a great historian?” While Rabbi Holtz saw the instrumental value of the publicity — more people reading Appelfeld — he knew that our value is determined by us, not by others.

In our tradition, we have one “story,” the telling of which is a mitzvah: sippur yetziat Mitzrayim, telling the story of our redemption on seder night. I spent many seders at the Holtz home, and beyond learning how to pass down the tradition of Yetziat Mitzrayim from generation to generation, I learned the “sippur” that Rabbi Holtz, along with his eishet chayal Dr. Toby Holtz, of how to pass on our mesorah — not the written text, but the Torah shel ba’al peh of day-to-day life—to the next generation, not just through books but through a meal around the family table, with a story.

At the core of what drew me to Rabbi Holtz is his embodiment of Kiddush Hashem. Of course, this came through in the traditional sense of showing how traditional Judaism goes hand in hand with mentchlechkeit, shown in the way he could relate to all Jews no matter what their background or level of observance. But beyond this, I saw a commitment to the core value of Kiddush Hashem — broadcasting the greatness of Judaism to this world. While the larger world saw this through his lifelong passion for Agnon, I saw this as he taught me — by actions more than words — that we should be committed to the Jewish people, the Jewish tradition, and, yes, the Jewish language, Ivrit. While many wonderful sefarim (and my own articles) have been written in English, we must be committed to carrying on the tradition in the words of our ancestors, which in our day have once become the daily speech of the land of Israel.

May his family find nechama in his memory and the many students who carry on his legacy, of which I am honored to be one. Yehi Zikhro Baruch — may his memory be for a blessing.