In Nedarim 62b, Rava asserts that Torah scholars are exempt from the “kraga,” or head tax. As Rav Steinsaltz notes, “kraga” is derived from the Persian “yarag” or “yarak,” meaning head tax, and, perhaps, the Arabic ḫaraġ comes from it. Rava’s basis is Rabbi Yehuda’s interpretation of Ezra 7:24. Achashveirosh wrote to Ezra — allowing a return of the Jewish populace to Israel — authorizing Ezra’s rule of Judea and Jerusalem by Torah law, and telling him to offer sacrifices. He further instructed the royal treasurers to grant funds and materials to Ezra, for Temple purposes, and that various Temple servants (such as kohanim, levi’im, singers, gatekeepers and other Temple servants) be exempt from various taxes: מִנְדָּה בְלוֹ וַהֲלָךְ.

Rabbi Yehuda explains each of these terms, and בְלוֹ is כֶּסֶף גֻּלְגָּלְתָּא, a head tax. This is a slight stretch, with Torah scholars analogous to the listed persons. Also, while Achashveirosh was king of Persia in centuries past, the Sasanian dynasty was a Persian dynasty which subsequently arose, and didn’t explicitly agree to this. This exemption draws power either from Torah law (since it arises from a biblical verse — see below) or is a legal claim that Achashveirosh set up this deal which is still in force.

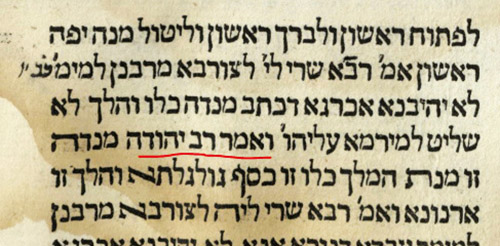

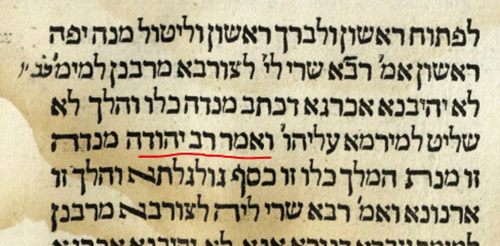

Note, I wrote Rabbi Yehuda. Who is this? The 1880’s Vilna Shas has וא”ר יהודה, so his title is ambiguous. Both Artscroll and Koren have “Rabbi” Yehuda (ben Ilai), the fifth-generation Tanna of Israel. It could work, in that he’s interpreting a biblical verse as Tannaim often do. But גֻּלְגָּלְתָּא is Aramaic. Further, aside from talmud Torah concerns, should he really care about the Persian tax code in the same way that Rava — a fourth-generation Babylonian Amora — would? In fact, the 1523 Venice printing explicitly spells out ואמר רב יהודה.

And that’s how it appears in all manuscripts of Nedarim 62b and of parallel in Bava Batra 8a, with “Rav” Yehuda bar Yechezkel — the second-generation Babylonian Amora — who set up Pumbedita academy. He’d be impacted by — and knowledgeable of — the Sasanian tax code.

In Bava Batra 8a, Rav Nachman bar Rav Chisda attempts to impose a head-tax on the rabbis (Presumably, this was in the city over which he presided, Drokart; see Taanit 21b.) Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak, who often gives him guidance (see again 21b), tells him that this violates Torah, Nevi’im and Ketuvim. The evidence from Ketuvim was the verse in Ezra coupled with Rav Yehuda’s exposition.

Scholastic Social Networks

There is an interesting scholastic social network at play. In Rav Nachman bar Yaakov’s yeshiva in Nehardea, Rava sat in the first row and Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak in the second (Eruvin 43b). While Rav Yosef was still alive in Pumbedita, Rava was a rosh yeshiva and Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak was a reish kallah, chief lecturer. Both Rava and Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak would know each other’s teachings and those of Rav Yehuda, who had established his academy in Pumbedita. They, then, express this teaching — about rabbis exempt from tax — in relevant contexts.

Let’s draw another scholastic social network and watch an idea propagate across it. Rabba bar Avuah’s student was Rav Nachman (bar Yaakov). Rav Nachman’s student was Rava. Rava’s students include Ravina I and Rav Adda bar Ahava II (who is really Rav Adda bar Abba).

In Nedarim 32b, a mishna says one prohibited in benefit (as opposed to eating) from a person by vow cannot walk across that person’s property. In the Gemara, Rav Adda bar Ahava II says that Rabbi Eliezer (ben Hyrcanus) authored this mishna, for he holds that even matters people typically overlook and forgive (such as excess in measuring for sale) is prohibited. Here, the implication is that people would forgive walking through their property.

In the bracketed additions to Masoret HaShas, Rabbi Yishayahu Pick enumerates all instances in which someone suggests a Tannaitic source is authored by Rabbi Eliezer, who holds that even overlooked (vitur) matters are prohibited in a vow against benefit. Aside from Nedarim 32b, there is Megillah 8a; Nedarim 33a, 48b; Bava Batra 57b.

The mishna in Megillah 8a, as part of a bunch of collections of אֵין בֵּין, is a mere shortened repetition of the Mishnah in Nedarim 32b. While the printings (Vilna, Venice and Pisaro) have Rava ascribe authorship to Rabbi Eliezer, the manuscripts (Gottingen 3, British Library 400, Munich 140) have Rav Adda bar Ahava, so that’s correct.

In Nedarim 33a, the subsequent mishnah adds a caveat. Although if one vows against food/ eating, which typically only includes indirect food preparation utensils, if some item/utensil is typically rented, then it’s also prohibited (perhaps, because money is fungible). The implication is that in the preceding mishnah, sieves, strainers and ovens would be prohibited, even if not typically rented. This prompts Rav Adda bar Ahava II to ascribe authorship to Rabbi Eliezer.

(While Tosafot deals with the duplicative effort, Rav Adda had already ascribed authorship, suggesting the weakness in the first proof. We might, alternatively, say this is a separate clause — that he’s demonstrating the idea from multiple vantage points — or even that this was transferred from close proximity by the Talmudic narrator.)

In Nedarim 48b, Ploni’s son illicitly seized flax, so Ploni imposed a vow prohibiting his son from benefiting from his possessions. They asked Ploni: “If your grandson became a Torah scholar, what would you do?” Ploni responded that he’d then want his son to acquire, in order to let his grandson inherit them. This is a case of קְנִי עַל מְנָת לְהַקְנוֹת, “acquire on condition you transfer.”

The Pumpeditans said that such is an invalid acquisition, while Rav Nachman (of Nehardea) said — pointing to evidence of a handkerchief acquisition — that it’s a valid acquisition. Rava objected to Rav Nachman — pointing to the preceding mishnah about the gift of Beit Choron — which was קְנִי עַל מְנָת לְהַקְנוֹת yet was invalid. To this, Rav Nachman sometimes answered one way — that in the mishnah, his wedding meal proves that he didn’t really intend to give the items — and sometimes another way — that the author of that mishna was Rabbi Eliezer, who prohibits even waived negligible benefit to a vower.

Finally, in Bava Batra 57a, the mishna discusses how placing certain items (such as animal or millstone) in a courtyard — with the owner not objecting — establishes ownership. Rav Nachman (bar Yaakov) cites Rabba bar Avuah that we’re dealing with a jointly owned courtyard, where neither partner is bothered by such placement. This is contrasted (by the Gemara) with a mishna in Nedarim 45b that partners who vow to benefit from one another cannot enter the joint courtyard. Upon this, Rav Nachman citing Rabba bar Avuah’s statement is revised. (By himself? By the narrator? By Rava?)

Then, Rava’s student, Rav Pappa offers one resolution of the original formulation — that since, sometimes, people are particular and sometimes not, the law leans leniently for monetary matters and stringently for ritual matters — that is — vows. Another of Rava’s students, Ravina I, suggests that the mishna in Nedarim was authored by Rabbi Eliezer. If so, Rav Nachman and his teacher’s initial resolution can stand.

Thus, we see the propagation of this idea (ascription to Rabbi Eliezer) within this scholastic social network, and only within it. Rav Nachman first used the idea to answer Rava, and then Rava’s students — Rav Adda bar Ahava II and Ravina I — have it in their toolbox to process other mishnayot, and even to resolve challenges to Rav Nachman.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.