I drafted a lengthy article about Nedarim 68-70—about the derashot and interpretations—according to Rava and according to Rabbi Yishmael’s academy. The impetus was that the derashot were distributed across sugyot, in a way that was hard to track all at once. However, that article was complex and essentially repeated fine details available in the Gemara. Also, we’re falling behind the Daf. So, here instead is a diagram—worth 1000 words—and a few observations and questions.

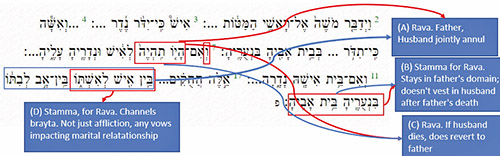

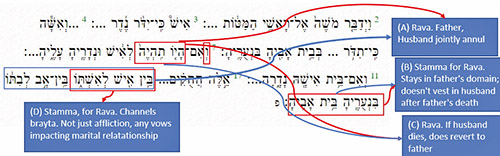

The sugyot deal with four laws: (A) The father and husband jointly annul a betrothed naarah’s vows. (B) It doesn’t revert to the husband upon the father’s death. (C) It does revert to the father on the husband’s death. (D) The husband can annul vows impacting the marital relationship. Rava explicitly derives A from the vav joining the father section and the husband section, and C from the doubled language of the same phrase. The Stamma (Talmudic narrator) fills in a derivation for B and D, operating on the assumption that each phrase must be interpreted and each law must be derived from a unique phrase. Those are the diagram’s red arrows. (Although, in print, it is Rava and Rabba—see manuscripts, and the phrase: לְאִידַּךְ דְּרָבָא.)

Meanwhile, Rabbi Yishmael’s academy explicitly derives A from a different source. The Stamma calculates how B and C are derived, and how available biblical phrases are utilized. See blue arrows. A few questions, after you learn through the sugyot with this diagram. (1) Does Rabbi Yishmael’s academy not maintain D? (2) If Rava indeed deduces A and C from different aspects of the same phrase (vav and doubling), then when the Stamma asks about ואם היו תהיה being available; how does pointing to law C help? For wouldn’t one phrase-aspect still dangle? (3) It’s strange for the vav bridges to derive C, as nothing about it implies C. (4) It’s strange for the doubling to derive C, for Rabbi Yishmael himself shouldn’t interpret doubled language. (5) In בֵּ֥ין אִ֖ישׁ לְאִשְׁתּ֑וֹ בֵּֽין־אָ֣ב לְבִתּ֔וֹת different aspects are interpreted. For D, it’s only the first subphrase; while for A, it’s the entirety and the juxtaposition. For Rava, the juxtaposition should still dangle, waiting for an interpretation. (6) Why need we deduce both B, no reverting, and C, yes reverting? Either B or C should be the assumption. (7) See Sanhedrin 34a about Rabbi Yishmael’s academy and deducing multiple laws from one verse. (8) See Sifrei on Bamidbar 30:7 and 17 for Rabbi Yoshiya and Rabbi Yonatan—of Rabbi Yishmael’s academy—interpreting these verses.

Rav Chisda’s Teacher?

Two weeks ago in this column, Rav Chisda dismissed a report by Rabba (or Rava), saying “Who will listen to you or Rabbi Yochanan, your rebbe?” We analyzed whether Rabbi Yochanan was truly Rabba/Rava’s teacher. However, there are four instances of אָמַר רַב חִסְדָּא אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן, in Pesachim 117a, Bava Batra 121a, Makkot 23a and Avoda Zara 27b. With כִּדְאָמַר instead of אָמַר, we also have Yevamot 25b, Bava Batra 120b and Bechorot 31a. Does such frequent citation indicate that Rabbi Yochanan is Rav Chisda’s rebbe? Can we reconcile this with the seeming disrespect and hostility we’ve seen elsewhere? What of Avot 6:3, requiring one to accord honor to one who taught you even a little Torah?

We can get back to only four citation instances by collapsing the כִּדְאָמַר instances with the Bava Batra 121b, אָמַר instance. In Bava Batra, Rav Chisda cites Rabbi Yochanan who interprets רָאשֵׁי הַמַּטּוֹת, “the heads of the tribes,” indicating that an individual expert sage can nullify vows. Let’s explore this citation further …

Primary Sugya

In our sugya, Nedarim 78a-b, we find the actual primary occurrence of this statement. A baraita had established a verbal analogy of זֶה הַדָּבָר between the prohibition of slaughtering korbanot outside the Temple and annulment of vows. Just as the slaughtering law was directed towards Aharon, his sons and all of Israel, so too, the annulment of vows. And just as annulment of vows was directed towards רָאשֵׁי הַמַּטּוֹת—the heads of the tribes, so too, was the slaughtering law. Rav Acha bar Yaakov, a third-generation Amora, explains the import of the former—that vows can be annulled by a court of laymen rather than a court of experts. The Gemara quite reasonably asks here: What of the words רָאשֵׁי הַמַּטּוֹת? (After all, the baraita itself had quoted רָאשֵׁי הַמַּטּוֹת!) To this, רַב חִסְדָּא וְאִיתֵּימָא רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן, Rav Chisda—and some say Rabbi Yochanan—said: We interpret this to mean that an individual expert can annul.

Shortly thereafter in the Gemara, Rav Asi bar Natan had trouble with ideas presented in different baraita. He went to Nehardea to ask Rav Sheshet. Since Rav Sheshet wasn’t there, he pursued him all the way to Mechoza. Rav Sheshet explained ben Azza’s statement in that baraita to mean that while the festivals require a calendrical expert, vows can be dissolved by a court of laymen. The Gemara asks, what then of the verse, רָאשֵׁי הַמַּטּוֹת, indicating (perhaps “a court or plural experts”)? Rav Chisda—and some say Rabbi Yochanan—aid: “We interpret this to mean that an individual expert can annul.”

In both instances, we see it isn’t Rav Chisda citing Rabbi Yochanan, but variant versions with וְאִיתֵּימָא between. Rather than וְאִיתֵּימָא transforming into אָמַר, I suspect that the variant appeared as a marginal note, and was incorporated in one text correctly as וְאִיתֵּימָא—a variant, and in others, both “amar X” and “amar Y” were copied. Perhaps, we should extrapolate to the other three citation instances, so Rav Chisda never cites Rabbi Yochanan.

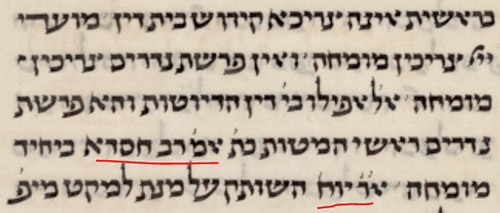

Why should these names swap? Well, in context, a chain of statements by Rabbi Yochanan both precede and follow these statements. And—immediately following the latter—Rav Chisda/Rabbi Yochanan statement, there is מֵתִיב רַב חִסְדָּא. One of the names bled over. I further suspect that there’s an orthographic error at play. “Amar rabbi” isn’t far from “amar rav” when אר was written with a diacritic (see image) over the resh. Yochanan and Chisda share a chet, and Munich 95 ends Chisda with a daled and diacritic—similar to a nun or nun sofit with a diacritic ending Yochanan.

Finally, of the two quotations in Nedarim, the former seemed primary to me. The baraita’s language prompts the question, and both question and answer fit well. The latter’s back-and-forth seems forced. Also, had the Talmudic narrator shifted the quote backwards, I’d have expected כדרב חסדא דאמר רב חסדא—as is the typical backshifting style. However, I think Vatican 110 is potentially highly informative here. For the former, it has כִּדְאָמַר רַב חִסְדָּא וְאִיתֵּימָא רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן … הָכָא נָמֵי בְּיָחִיד מֻמְחֶה. For the latter, it only has Rav Chisda. And in the juxtaposing statement, it has ר”יח —instead of our Rabbi Chanina—which might be the source of the bleed.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.