One of the primary reasons we care about which Tanna or Amora said what, is as follows. We assume that his opinion, worldview and halachic framework is consistent. Thus, ideas established elsewhere can aid in understanding his position locally. Let’s see how this plays out for Rabbi Meir and for Rabbi Zeira.

The Mishna (Kiddushin 1:3) lays out a dispute between Rabbi Meir and the Sages. Rabbi Meir maintains that a Canaanite servant may be freed via cash payment only if a third party gives the cash to his master. The Sages maintain that he can give the money himself, provided that the money comes from others.

Tannaim seldom spell out their reasons in Mishnayot and braytot. Instead, we are provided with a case where Tanna X and Tanna Y disagree as to the law, and we (or Amoraim) can theorize as to the underlying legal theory of X and Y. For servant-freeing, the obvious distinction (heretofore labeled reason A) is whether the Canaanite servant can own property. After all, any work he performs, or lost article he finds, is acquired by his master. So, when the money comes from others, is there any moment at which he owns it and can use it to free himself?

Indeed, we see this idea of personal property ownership spelled out in several Mishnayot. For instance, the Mishna in Eruvin 7:8 discusses how to create a shituf muvaot to allow people of different courtyards in a joint alley to carry in that alley. One person places a barrel filled with his own food, and uses a third party to confer possessions to the partners in the shituf. He obviously cannot use himself, for that is placing it into his own hand. The Mishna states: וּמְזַכֶּה לָהֶן עַל יְדֵי בְּנוֹ וּבִתּוֹ הַגְּדוֹלִים, וְעַל יְדֵי עַבְדּוֹ וְשִׁפְחָתוֹ הָעִבְרִים… אֲבָל אֵינוֹ מְזַכֶּה לֹא עַל יְדֵי בְּנוֹ וּבִתּוֹ הַקְּטַנִּים, וְלֹא עַל יְדֵי עַבְדּוֹ וְשִׁפְחָתוֹ הַכְּנַעֲנִים, מִפְּנֵי שֶׁיָּדָן כְּיָדוֹ. That is, his adult children and his Hebrew servants … can act as a third-party, but his minor children and Canaanite servants may not, because their hands are like his hands.

Reason A isn’t universally accepted. While the Talmudic Narrator (Kiddushin 23b) proposes it to explain the Mishna in Kiddushin, others propose a different legal basis for the dispute. However, let’s run with reason A. If true, we can ascribe authorship of any Mishna or brayta that employs יָּדָן כְּיָדוֹ to Rabbi Meir, a fifth-generation Tanna. And, his disputants would likely be his fifth-generation contemporaries, such as Rabbi Yehuda, Rabbi Yossi and Rabbi Shimon.

This brings us to our local Mishna (Nedarim 88a). A man has taken a vow, forbidding his son-in-law from receiving any benefit, yet wishes to give something to his daughter. He should say to her, “the money is given to you as a gift, provided your husband has no rights to it, the gift only including that which you pick up and place in your mouth.” Rav maintains that this last phrase, מָה שֶׁאַתְּ נוֹשֵׂאת וְנוֹתֶנֶת בְּפִיךְ, is deliberate and must be said, while Shmuel maintains that “do as you please with it” has the same effect. (This may be a debate about how to understand the Mishna, or whether to rule like the Mishna.)

At this, Rabbi Zeira seemingly objects. For according to whom would Rav attribute the Mishna? To Rabbi Meir, who holds that a woman’s hand is like her husband’s hand. (As previously noted, Rabbi Meir never says that explicitly, but he’s the one who maintains this by the servant’s hand, while the Sages aren’t concerned with this.) Yet, we can object based on the Mishna in Eruvin 7:8 mentioned above. I cleverly used an ellipses (…) to obscure that one of listed persons who could function as a third party was אִשְׁתּוֹ, his wife. Thus, Rabbi Meir wouldn’t extend from a Canaanite servant to a wife. Then, Rava responds to the contradiction, explaining why eruv is different—she has in mind to acquire it for others.

I’m not convinced that Rabbi Zera truly objected here. Yes, in Bavli, his statement is introduced with מַתְקֵיף, but that sort of connective tissue language was fluid until quite late. He could have just explained the attribution to Rabbi Meir, while the וּרְמִינְהוּ introducing the contradiction is standalone, just like the וּרְמִינְהוּ on 87b to which Rava responded.

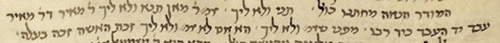

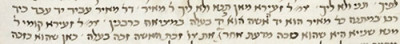

I suspect this is the case because of the parallel Yerushalmi sugyot. The Gemara in the direct parallel (Y. Nedarim 11:8) just says that “Rabbi” attributes the Mishna to Rabbi Meir. However, I believe that this is an error of haplography for “Rabbi Zeira.” For aside from our Bavli, the parallel in Yerushalmi Kiddushin 1:3 discusses our Mishna in Nedarim and has אָמַר רִבִּי זְעִירָא, מָאן תַּנָּא וְלֹא לֵיךְ? רִבִּי מֵאִיר, דְּרִבִּי מֵאִיר עֲבִיד יַד עֶבֶד כְּיַד רַבּוֹ.

That Yerushalmi Kiddushin parallel also discusses how the Mishnah in Eruvin fits into the picture. The answer, from (fifth-generation Amora of Tzippori) Rabbi Chanina citing (fourth-generation Amora of Teveria) Rabbi Pinchas, is that there different Tannaim understand fifth-generation Rabbi Meir differently, as to whether he extends ידן כידן from the Canaanite servant to the wife. Our Mishna in Nedarim maintains that this rule extends to his wife. Meanwhile, another sixth-generation Tanna, Rabbi Shimon ben Eleazar understands Rabbi Meir such that it doesn’t extend to his wife. The evidence for this is this Tannaitic source (which in Bavli, Rava explains in another fashion). The source: רִבִּי שִמְעוֹן בֶּן אֶלְעָזָר אָמַר מִשּׁוּם רִבִּי מֵאִיר: אִשְׁתּוֹ פוֹדָה לוֹ מַעֲשֵׂר שֵׁינִי. This means that a wife may redeem her husband’s maaser sheni without paying the additional fifth. Now, only the owner himself must add the fifth, not a third-party, so Rabbi Shimon ben Eleazar must understand Rabbi Meir as not extending the rule to his wife.

Third-generation Amora Rabbi Zeira began in Bavel but migrated to Israel and is associated with Teveria. It makes sense that he’s in agreement with Rabbi Pinchas’ framework. As such, I’d reiterate my suspicion that in Bavli, Rabbi Zeira had no objection, only an attribution.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.