Englewood—Commitment to work, commitment to family, and commitment to the tenets of our faith are the overarching themes encountered in a newly revised book by Norbert Strauss. In it, valuable lessons can be gleaned by future generations about the immense benefit of a strong and steady work ethic, which involves taking on purposeful work on behalf of the community in addition to work for a living.

In My Stories: Highlights of My Life, Strauss relates with a great detail of clarity his lineage and childhood in Bad Homburg, Germany, where he was born in 1927, his family’s escape from their subsequent home in Frankfurt am Main in 1941, and his struggles and ultimate success in America—in school, in the Army, in business and in volunteer work. He has spoken extensively to organizations and school groups, relaying his Holocaust story, in both Germany and America, always without payment. In fact, Strauss will be speaking at Frisch High School on April 28, 2014, as part of their Yom HaShoah commemoration program.

Today, Strauss is a celebrated volunteer who has logged more than 28,000 hours working in both the employee benefits and Center for Nursing Practice offices at Englewood Hospital and Medical Center. “I prefer to be known as an unpaid employee,” he told JLBC.

Steady, strong longevity may in fact be the most unique and special part of Strauss’s story. “My commitment is always long term,” said Strauss. Married to Trude Strauss, z”l for 61 years, he spent 36 years at Philipp Brothers, the metal trading company he started working for shortly after his graduation from college in 1949. Now he has completed 21 years of unpaid service to Englewood Hospital.

Arrival in America in January of 1941 presented a less than auspicious beginning for the Strauss family, not only because the packed belongings of the family never made it on board their ship. The crates had been sent ahead and stored in a warehouse in Portugal, but when the time came to have them loaded, there was no money left to pay the warehouse and transportation charges, as they had been on the run from the Nazis. Their escape took them from Frankfurt to Munich, then Stuttgart, on to Lyon, France, to Madrid, Spain, and then finally to Lisbon, Portugal, where they boarded the SS Siboney. They arrived in America with only the suitcases that they had been able to carry and the clothes they had been wearing.

With his mother and brother, Strauss arrived in New York 21 days after they left Frankfurt. Strauss was 13 years old. His journey, however, was much less difficult than his father’s, who had escaped Germany 20 months earlier, initially on the ill-fated 1939 journey of the SS St. Louis, made famous by the film Voyage of the Damned, in which 937 Jews were denied entry to various ports in Cuba, America, and Canada, and were forced to return to Holland. The elder Strauss, with no money to bribe anyone, was told he would never get a visa to America, but, in what he referred to later in life as a nes min hashamayim (a miracle from heaven), he received an unsolicited postcard from the U.S. Consul’s office telling him to come pick up his visa. He arrived in New York on the SS Staatendam with more luggage and valuables than the rest of his family would have, was received by relatives, and found a home for his family in Washington Heights, where many German Jews lived when they first arrived.

The younger Strauss remarked on his first meal upon arrival. “Neither Herman (Strauss’ brother) nor I knew what to do with the knife when it came to the meat dish, not having eaten any meat in so many years. When we took the chicken bones into our hands, not wanting to waste even one shred of meat, we were told in no uncertain terms by Opa (Strauss’ father) that “mann macht dass nicht,” one does not do that in public, Strauss wrote.

Strauss shared the difficulty his family had in initially finding work and surviving. “Jobs were hard to find in those days, especially if you were an Orthodox Jew and needed to leave early on Friday afternoons in the winter, as well as be off on the Jewish holidays. But Opa never wavered; giving up on his beliefs was not an option. As time went on, the family had to sell off the silver houseware items that Opa had been permitted to take out of Germany in order to put bread on the table and to buy new school clothing for the boys,” he wrote.

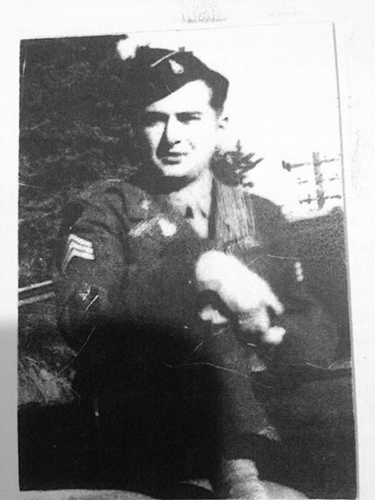

Eventually, Strauss’ father was able to establish himself in business, a wholesale hides and skins operation, the same type of business he had had in Germany. Strauss helped him until it was time to go to college and the Army. School was initially difficult; however, both brothers caught up relatively quickly. After finishing high school and beginning college studies at CCNY in engineering, Strauss was drafted in 1945. He was sent to Korea and was able to secure an office job there due to his mother’s social connection with a “Mrs. Kissinger” in Washington Heights, whose older son Walter was a high-ranking civilian employee for the Army. Walter’s younger brother, Henry, later became Secretary of State.

Returning home from the Army, Strauss switched majors in college from engineering to business. When Kissinger plucked him out of the infantry and set him up with an office job in the Korean Department of Commerce, he caused Strauss to change his academic interests because of the opportunities he was afforded, the proficiencies he showed, and the fast advancements he made. He started as an office clerk with the military rank of Private First Class, but left the army with the military rank of sergeant, with the dual title of Sergeant Major for the military personnel and Chief Clerk for the civilians. He had been promoted almost three times in approximately ten months.

At this point, Strauss went on the only two job interviews for paid work that he had his entire life. His interview at Philipp Brothers took 15 minutes. He spent the next 36 years working there, until taking early retirement in 1985.

After Strauss’ departure from Philipp Brothers, he decided what he really wanted to do was “to pay back some of what I felt my family owed to society. The United States had given me a new home; I had a wonderful and healthy growing family. More I did not need. It was payback time,” he wrote.

“All my life I have been involved with volunteer work in one form or another. It started as far back as 1947, after I was discharged from the army,” Strauss wrote. A group he worked with, the Overseas Relief Committee in Washington Heights, collected donations of food, clothing, and shoes that were sent to European Displaced Persons camps.

“When you volunteer, you have to be committed. You have to do the interesting things, and the not so interesting things. It’s part of work. It has to be done, so I do it,” he told JLBC.

Strauss, who lives in Teaneck with his new wife, the former Dorothy Knapp, has eight grandchildren and 18 great-grandchildren. The revised edition of My Stories: Highlights of My Life is dedicated to the memory of his first wife, Trude, who passed away in 2012. Those interested in obtaining a copy of the book are invited to email nstrauss18@optonline.net.

By Elizabeth Kratz