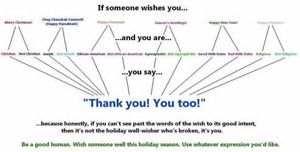

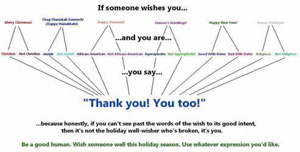

In recent weeks, this image has appeared in my Facebook newsfeed several times:

(Note: I tried unsuccessfully to find the original source of this graphic; the link provided goes to just one of the pages on which I have seen it.)

The chart is cute, and catchy, and at first glance it’s easy to think it reflects the values of our modern world and all its respect for diversity. But when I look past the design and the confidence of its tone, I find a message that is the exact opposite of respect for diversity.

I like to think I have a greater capacity for complexity and nuance than the average meme. So unlike the above graphic, I am able to do two things at once: I can simultaneously appreciate the good intent behind any of these good wishes, and feel it is important to counter the assumptions behind it.

I think those assumptions reflect a break in society that runs deeper than any particular brokenness I would presume to ascribe to any individual well-wisher, or to myself.

There is a break in society when people can’t accept, when it doesn’t even occur to them, that maybe Christmas is not my holiday and December is not my holiday season. There is a break in society whenever people make assumptions about others, without the simple courtesy of asking for information.

If anyone bothered to ask, I would tell them that no, I don’t celebrate Christmas; and Chanukah, while a lovely and meaningful holiday, does not make this my “holiday season.”

Really, though, no one needs to ask. I don’t expect, or want, a full interview from every cashier or stranger on the street who would like to say something nice to me. We’re all busy; it’s really fine.

And because we’re all busy, there are times that I’m wished a “Merry Christmas” or whichever, and I do respond “Thank you! You too!” – because it’s easier. But “easy” is not the same as “right.” I think what I should say is something more like “Actually, I’m Jewish, but thank you for the thought and I hope you enjoy your special time!”

I think it is important to correct unfounded assumptions, with an eye towards building a society in which we all question our assumptions about each other.

Which is, of course, really hard to accomplish. I get that. We all make assumptions: who we are is so ingrained that it can be really tough to imagine the ways in which other people might be different.

My husband received a gift last year from a patient with whom he had discussed some Bible texts. It’s a wonderful thing: He’s Jewish, she’s Christian, but they were able to engage over a shared text. Apparently, their conversations were meaningful enough that she wanted to give him a Christmas gift that reflected their connection – and she chose a small, ornamental crucifix.

Really? A crucifix? Did she miss the part where he told her he was Jewish? Did she not see that thing on his head, broadcasting his Jewish faith for all to see?

Contrary to the implications of the Facebook graphic, my husband and I found that we were capable of a whole range of reactions to this gift. Such a nice thought, and it’s the thought that counts. And yes, it can be really hard to step outside oneself and imagine how someone else might possibly be different.

But.

A crucifix?! We were baffled.

What kind of pluralistic 21st century society is this, that we boast about our progressive attitudes and our acceptance of others – yet a grown woman, with schooling and years of life experience, apparently can’t conceive of the possibility that someone of another religion might not find a symbol of her faith personally meaningful?

(Perhaps, on some level, she thinks of Judaism as some sort of Christian sect? Like a co-worker of my mother’s who once asked the bewildering question, “I know Jews don’t celebrate Christmas, but when DO you celebrate the birth of Christ?”)

In our day and age, people should at least be aware of the simple fact that other religions exist, and should think before assuming that another individual must necessarily share one’s own religious views or symbols.

We should be past the “melting pot” metaphor; I’d rather have a salad. You can be a tomato, and I’ll be a cucumber, and we’ll live in the bowl with the lettuce and all the colorful peppers, and I’ll do my best to notice who you are before mindlessly wishing you a “happy green peel day.”

And I won’t ever wish you a happy Christwanzakkah, any more than I’ll call you a letatopepumber. Because that’s not who I am, or who you are, and it risks diminishing us both. Unless, of course, I’ve asked and learned that your unique identity IS a combination of all of those, and that it’s something YOU do wish to celebrate.

Being a “good human” does not mean blurring distinctions in how we view others or in how we allow ourselves to be viewed. It means learning to recognize that people might have different perspectives, and behaving with some degree of sensitivity to those differences.

So instead of telling each other to pluralistically play along with other people’s assumptions about us, let’s decide together to pluralistically ask each other what we’re all about, and relate to our differences with genuine respect.

At the same time, of course, we would do well to remember that there is plenty to unite us. Is it so hard, after all, even in December, to simply smile and say “Have a nice day?”

By Sarah Rudolph