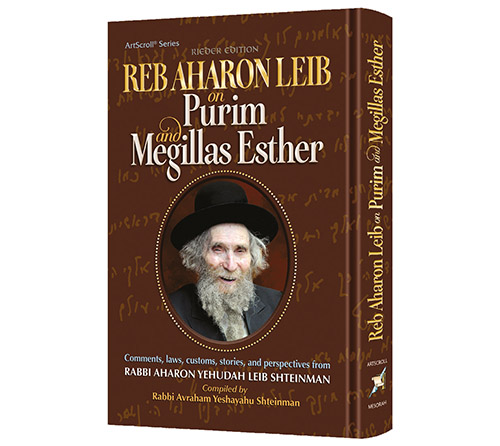

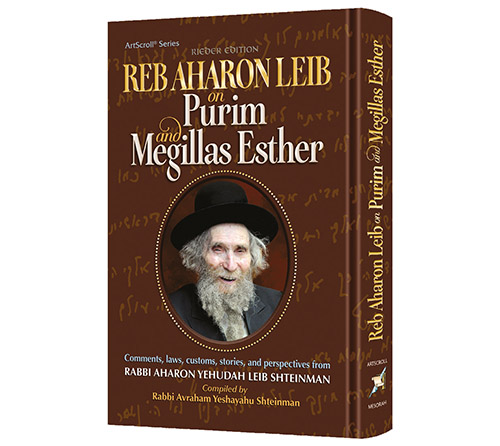

(Courtesy of Artscroll) Whenever the Megillah mentions the word melech, it is alluding to the King of the universe. Accordingly, “the king’s gate” alludes to the gates of Heaven. How can a person enter the gate of Hashem?

We can answer this according to R’ Yechezkel Abramsky’s explanation (cited in Peninei Rabbeinu Yechezkel) of the verses: פִּתְחוּ לִי שַׁעֲרֵי צֶדֶק אָבֹא בָם אוֹדֶה יָהּ. זֶה הַשַׁעַר לַה’ צַדִּיקִים יָבֹאוּ בוֹ, Open for me the gates of righteousness; I will enter them and thank God. This is the gate of Hashem; the righteous shall enter through it (Tehillim 118:19-20). Why do these verses begin with the plural form—שַׁעֲרֵי צֶדֶק, the gates of righteousness—and conclude with the singular form, זֶה הַשַׁעַר לַה, this is the gate of Hashem?

These verses actually contain a question and answer. David Hamelech requested, “Open for me the gates of Heaven”—in plural, for he sought many gates and paths to serve Hashem. But the answer he received was that there are no “gates”; there is only one gate—זֶה הַשַׁעַר—to serve Hashem, and that gate is ‘לַה, meaning that your motivation should be to act for the sake of Heaven. That is the one and only gate through which a person can enter to serve Hashem.

Alternatively, the Noam Elimelech interprets the words פִּתְחוּ לִי שַׁעֲרֵי צֶדֶק to mean that the righteous always live with the feeling that they have not yet accomplished anything, and are still standing at the entrance to the gates, just beginning their service of Hashem. But if a person always feels that he is standing at the gate, that itself is a sign that he is a tzaddik: זֶה הַשַׁׁעַר לַה’ צַדִּיקִים יָבֹאוּ בוֹ.

R’ Shlomo Levenstein related:

Once, when I came to R’ Shteinman’s house, he told me this story, which he heard from the owner of a factory.

A theft took place in this man’s factory, and he suspected that a certain employee was responsible, so he approached him and asked him innocently if he knew anything about the matter, and who the thief might be. Of course, the worker pretended he had no idea.

The owner decided to install hidden cameras throughout the factory, without the knowledge of the workers. A while later, another theft took place, and merchandise of great value disappeared. The owner scanned the footage and discovered that this employee was indeed the thief: The camera had recorded him removing the merchandise from the factory.

The owner summoned this employee to his office and asked him, “Do you know who the thief is?”

Again, the employee feigned innocence. The factory owner then played the video before his astonished eyes, and within a few seconds, the man collapsed in a faint.

A moment earlier he had denied any connection to the theft, and suddenly he was confronted with the bitter truth, as he witnessed his own disgrace. Overcome with shame, he fainted.

After recounting this story, R’ Shteinman turned to R’ Shlomo Levenstein and said, “There is a powerful lesson here for us. All our actions and thoughts are documented, down to the very last detail. Even our subtlest innermost thoughts are recorded, and they will all be presented to us in the future to come. When we arrive in the World to Come and view our own personal video, how many times will our souls depart from us, as we faint from seeing the bitter truth before our eyes? How ashamed we will be!”

R’ Shteinman then burst into tears and told R’ Shlomo, “You are still young; you can still rectify yourself and fill in what you have lacked, but I am already old, and soon I will have to give an accounting. What will be with me?”

He continued to weep bitterly.

Indeed, tzaddikim always live with the feeling that they have not yet accomplished anything; they are sure that they are still standing at the gateway. Their achievements, and the spiritual levels they have attained, are meaningless in their eyes.