Part II

There is other intriguing evidence for the existence of Jews in the Roman colonies of Pannonia and Dacia (the Roman names for modern Hungary and Romania respectively).

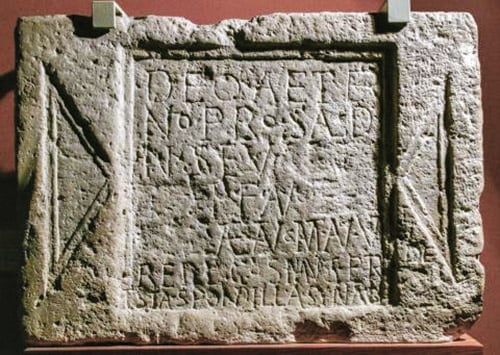

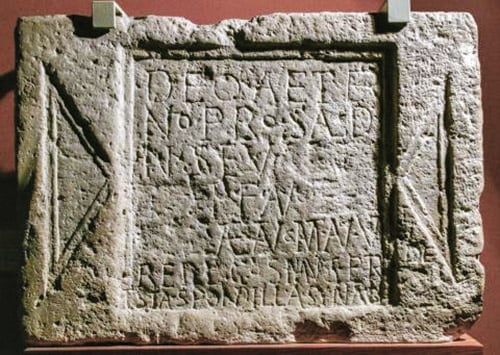

A plaque discovered in the Roman ruins of Intercisa (now Dunaújváros in Hungary) carries the following inscription: “To the Eternal God. For the salvation of our Lord the pious, felicitous Emperor Severus Alexander and the Empress Julia Mamea, mother of the Emperor; Cosmius, chief of the Spondilla customhouse, head of the synagogue of the Jews, gladly fulfills his vow.”

This inscription was first recorded in 1864, when it was discovered having been built into a wall of an outbuilding at the post office of Dunapentele, Hungary, near the Roman site of Intercisa. It is a dedication invoking divine support for the health and welfare of the emperor, Alexander Severus, and has been considered an important text for the evidence it provides of a Jewish community there in the early third century CE.

Scholars are not of one opinion on whether there was a continuous Jewish presence in any of these areas, despite intermittent bans and expulsions, (It should be noted that the vast majority of Hungarian and Romanian Jews had settled in those areas from the 19th century onwards, coming chiefly from other parts of Eastern Europe such as Poland and Galitzia, to escape poverty and oppression), a similar argument is now raging in Ashkenaz proper.

The Jewish community of Cologne in western Germany on the banks of the Rhine River is documented from the year 1135, but systematic excavations of the Jewish quarter, which have been going on since 2007, have uncovered findings dating back to Roman times when the place was called Clolonia Agrippina (Agrippina Colony).

German archeologist Sven Schütte, who was in charge of the excavations of the Jewish quarter of Cologne (before being controversially replaced) believes that there was a continuous Jewish presence in the city of Cologne from the late Roman era right up to the Middle Ages.

Schutte claims that the site has been inhabited by Jews since the 1st century and cites as evidence the findings of coins bearing the infamous legend “Judea Capta” (Judea has been captured). However, hard evidence for Jewish habitation of Cologne dates back to 321 when Roman emperor Constatine passed a decree permitting the appointment of Jews to the city’s governing body. It would be logical to assume that the Jewish community was already established at that point with a synagogue, however, the question remains: Was this the same community that we find in the Middle Ages? Schütte is convinced that that is the case and claims that the ancient structures found underneath the “modern” synagogue is the old synagogue from the Roman era which was destroyed in an earthquake. However, there is no written evidence between the years 321 and 1000 to support Schütte’s hypothesis.

Other scholars counter this contention and bring several proofs to back it, including the fact that when the Jewish community was expelled from Cologne in 1424, the city chronicle stated that the synagogue had existed for 414 years, which means that it must have been founded in the year 1010.

Other communities in medieval Ashkenaz (for instance, Regensburg) claimed to have origins in pre-Christian times, whereas such a tradition didn’t exist in Cologne.

In fact, in the early 12th century, Mainz was considered the oldest community in the region. This claim ties in neatly with the Kalonymos story (which describes an emigration of a prominent Jewish family from Lucca, Italy to Mainz that laid the foundation for the flourishing of Ashkenazi Jewry—more on that in a future installment).

A major archaeological park is planned for ancient Cologne and construction has been continuing for several years. The many soon-to-be-displayed finds include inscriptions, fragments of furniture, books, burnt parchment, toys, medicine bottles, food waste—and even a 13th century toilet with an inscription in Hebrew.

“No other German city has such a longstanding connection with Jewish history as Cologne,” the city’s mayor, Henriette Reker, said at the cornerstone laying ceremony.

However, as mentioned previously, the communities of Shum were traditionally held to be the most ancient in Ashkenaz. Shum is an acronym for Speyer, Worms and Mayence. Some interesting Jewish traditions that may shed some light on this: Rabbi Yosef Yuzpa of Worms (1604-1678) recounts an old tradition in his book wherein the Jews had settled there after the destruction of the First Temple, where they built a grand synagogue. When Ezra the Scribe tried to galvanize the Jews of the Diaspora to return and build the Second Temple, these Jews refused, saying, “Why should we go back to Jerusalem when we have built a Jerusalem of our own?” Rabbi Yuzpa connected the horrific suffering experienced by this community—first under the Crusaders in 1099 and later during the Black Death—to that event.

The famed Halachic decisor Rabbi Yaakov ben Moshe Levi Moelin (1365-427), known as the Maharil, was born in Mainz. A tradition is related in his name wherein the Jews of the city have been settled there since the days of the Second Temple. He writes, and I paraphrase: “He has seen in a work that they wrote to the Jews of Mayence during the time of the episode of Jesus, to pray for mercy that (the decree) be annulled…He also related that a tombstone of a half-maidservant, half-free woman dating back 1100 years was once discovered.”

אמר מהרי”ל שראה בקובץ אחד שכתבו ליהודי מגנצא בזמן מעשה ישו לבקש רחמים שיבוטל, והיה כתוב בה קהלת מגנצא..ועוד אמר שפעם נמצא מציבה והיה הפרט מיום קביעות עד היום ההוא י”א מאות שנה והיה כתוב בה שפחה חרופה.

This passage is unclear and there are several different interpretations. I am inclined to disagree with the scholar Avraham Grossman’s conclusion in his book “Chachmei Ashkenaz Harishonim,” wherein he contends that the apocryphal tradition that the Maharil cites does not denote that the Jews prayed for the abrogation of Jesus’ punishment, but rather that the Ashkenazim claimed that they were already in Ashkenaz during that time, and therefore should not be held culpable for the charge of deicide. I understood the tradition to mean that the proto-Ashkenazim did, in fact, pray that the entire debacle should end (and that Jesus should be spared—not because they necessarily believed in his innocence, but rather because they foresaw the danger that would arise from the affair).

To be continued..

By Joel Davidi Weisberger

The author is available for scholar-in-residence and other speaking engagements and can be reached at yoelswe@gmail.com.