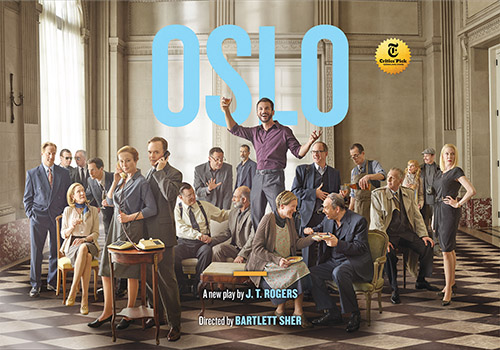

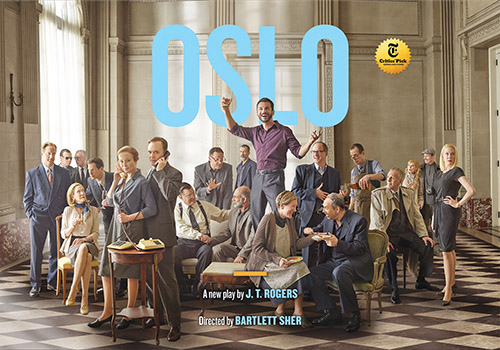

“Oslo,” by J.T. Rogers, currently at the Vivian Beaumont Theatre, is masterfully written and performed. It recently won a Tony Award for Best Play and received seven nominations. That’s both impressive and extremely dangerous. The play is a dramatization of the beginnings of the secret talks in Norway that led to the Oslo Accords and the iconic photo on the White House Lawn with Yitzhak Rabin and Yasser Arafat standing beside a very pleased-looking President Clinton. The stalemate had been broken. A peaceful resolution to an old problem had finally come to life under his watch, hadn’t it?

Of the three political leaders, only Clinton is still alive. Two years after that handshake, Yitzhak Rabin was assassinated by Yigal Amir, a law student at Bar-Ilan University. Amir was infuriated by his government’s decision to give up land won in a defensive, existential war to a belligerent terrorist who was an avowed enemy of Israel. The Palestinian concession was little more than a promise to end the terroristic violence against Jewish civilians and soldiers.

Whether an actual and lasting peace would have been achieved if Rabin had not been murdered remains questionable. By 1993, Palestinians, indeed the Muslim world, had been brainwashed to believe that it was just a matter of time until Israel would be routed. Already, their continued harassment of Christians in the Middle East had seen a significant decline in that population—a victory for Islam.

Only now that terror is being wreaked on their own people in their own lands is it finally becoming increasingly clear to Western democracies that not only has their money been woefully wasted, but also their hopes. Hope was what drove the secret talks that led to that historic handshake, the hope that by talking and listening to one another, the opposing parties would resolve a seemingly insoluble problem.

Conflict-resolution methodology includes addressing all aspects of disagreement, however minor. At times during the course of Rogers’ long play, it seems that every single issue will be addressed. What’s remarkable is that such a small cast with little opportunity for action, a rather simple set, dull costumes, some banal dialogue and a few stale jokes can produce a riveting experience for the audience.

The play is dangerous because it “has legs.” The compelling subject, small cast, minimal production values and the prestigious awards it has garnered thus far ensure its success as a commercial venture for years to come.

Five centuries after the debut of Shakespeare’s “Merchant of Venice,” Shylock is now a pejorative noun. With its allusion to the Blood Libel, it’s come to mean a heartless, vengeful, relentless moneylender. It’s also believed to be the origins of “shyster,” the word for a deceiver. According to the Bible, creation began not with an act but with the words, “Let there be…” Words wield power. Insults hurt the insulted not only when first uttered; they can echo throughout life and often beyond death.

There is ongoing scholarly debate about whether or not Shakespeare intended Shylock as a sympathetic character. Indeed, there have been productions in which he is portrayed that way: a lonely widower mourning his beloved wife, a businessman being pushed into a bad deal that will ultimately cost him everything, a father betrayed and abandoned by his only child. But plays can be staged in various ways, and not all productions illuminate this play in all its personal and historical complexities. How many seeing the play know that moneylending, despite church teachings on usury (based on Torah law), was not relegated only to Jews? Christians, too, engaged in moneylending, and “The Merchant of Venice” was inspired by the story of a Christian moneylender. Five hundred years after it was first performed, Shakespeare’s play breeds and fosters anti-Semitism (however unintended) among people who have never seen or met a Jew. One can only hope that “Oslo” will not do the same and take comfort in the fact that Rogers is hardly Shakespeare.

By Barbara Wind