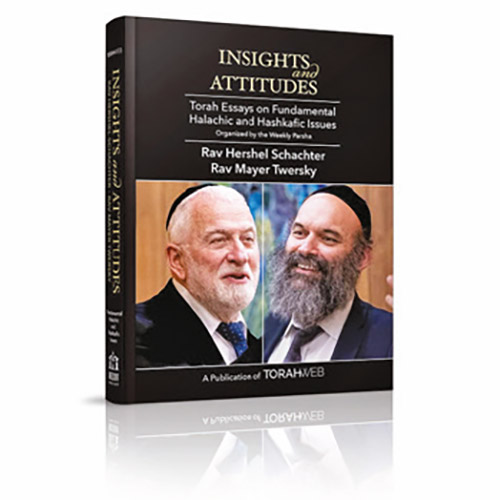

Editor’s note: This series is reprinted with permission from “Insights & Attitudes: Torah Essays on Fundamental Halachic and Hashkafic Issues,” a publication of TorahWeb.org. The book contains multiple articles, organized by parsha, by Rabbi Hershel Schachter and Rabbi Mayer Twersky.

When Yaakov returned to Eretz Yisrael, he “encamped” (“vayichan”) on the outskirts of the city of Shechem (Bereishis 33:18). The Rabbis of the Talmud (Shabbos 33a) understand the pasuk to imply that in addition, he improved and beautified the city, either by instituting a coin system, a public bathhouse, or a shopping mall. The Midrash understands yet an additional level of interpretation on the phrase “vayichan,” that Yaakov established his techum for Shabbos purposes (see Meshech Chochma). The halacha declares that at the start of Shabbos, each Jewish person has to determine where his home is, and he has a very limited area around his home where he may roam about. Yaakov established his home and determined where his limited area of walking would be.

The Torah (Bereishis 23:4) quotes Avraham Avinu as telling the bnei Cheis (who lived in Kiryas Arba) that he was both a stranger and a regular citizen dwelling among them. These two terms are mutually exclusive! If one is a regular citizen, he is not at all a guest or a stranger, so how did Avraham describe himself as being simultaneously a stranger and a citizen? The answer obviously is that all religious Jews relate to the outside world in a dual fashion (see “Confrontation” by Rav Yosef Dov Soloveitchik, Tradition, summer 1964, pp. 26-27).

In many areas we work along with everyone else as full partners. We all use the world together and have a reciprocal obligation toward each other to make it more livable and more comfortable. When we were born we entered into a world full of beautiful trees, a world with hospitals, medications, etc. Therefore we all have an obligation to provide such conveniences and institutions for the next generation (see Ta’anis 23a). All of mankind is considered one big partnership in a certain sense, just as all of the people living in the same community are considered to be in a partnership, and are therefore obligated to contribute towards that partnership – in order to further develop it – in accordance with the wishes of the majority of the partners (see Shulchan Aruch Choshen Mishpat 163:61. See also “Taxation and Dina DeMalchusa,” below in this volume, page 298).

Yaakov Avinu, like his grandfather Avraham, felt obligated to establish shopping malls etc. to improve everyone’s quality of life. Yes, we are all obligated to participate in all civic, scientific, and political enterprises which will enrich the lives of the entire community.

But at the same time the religious Jew has his own unique outlook on life and style of living. The tradition of the Talmud was, based on the pasuk in Eicha (2:9), that although there is much chochma (knowledge and wisdom) to be gained from the secular world, but “Torah”, i.e. a way of life and an outlook on the world, can not be picked up from the other disciplines. These can only be acquired through the revealed truths of the Torah.

Avraham Avinu says that although he is, on the one hand, a full-fledged citizen, at the same time he feels he is a stranger amongst his non-Jewish neighbors. Not only does he lead his life differently from them, even after death he may not bury his spouse, Sara, in the regular cemetery. Even in death, the Jew stands alone. And similarly Yaakov, despite the fact that he was involved in improving the entire society, nonetheless felt it necessary to chart out his techum, indicating that he can not “go out of his box” to mingle freely with all of his neighbors. He is absolutely unique and alone. The Torah mentions the fact that the Jewish people always stands alone (see Bamidbar 23:9), and this is linked (Devarim 33:28) to the “standing alone” of Yaakov Avinu.

Immediately after the mention of the fact that Yaakov wanted his family to stand alone, the Torah relates what tragedy followed (perek 34) when Dina decided to disobey her father’s instructions and mingle with the local girls her age.

The Torah commanded us (“ושמרתם את משמרתי”; Vayikra 18:30) to introduce safeguards to the mitzvos (seeYevamos 21a). Not only are we biblically forbidden to carry in a reshus harabbim, we must also abstain from carrying in a karmelis, lest we forget and carry in a reshus harabbim. Not only are we biblically prohibited to eat meat cooked with milk, we should also avoid eating chicken with cheese, lest this will lead to eating real basar bechalav. Rabbi Moshe Chaim Luzzatto wrote in his classic work Mesillas Yesharim that the Torah’s command to “erect a fence” (“עשו סייג לתורה” – Avos 1:1) around the mitzvos, to protect us from even coming close to sin, is not addressed only to the rabbis. Each individual must introduce personal “harchakos” (safeguards) depending on his or her particular situation.

The Torah relates (Bereishis 35:2-4) that Yaakov disposed of all the avoda zara in his possession, which his children had taken from Shechem. The commentaries point out that the avoda zara ought to have been burnt. Why didn’t Yaakov destroy them? The suggestion is offered (see Seforno) that the people of Shechem had already been mevatel these avoda zaras, so strictly speaking, they had already lost their status of avoda zara. Yaakov’s disposing of them was a chumra that he thought appropriate in his circumstance.

A man like Yaakov who is very involved in the outside world, establishing shopping malls, etc., has to accept upon himself additional chumros and harchakos to prevent himself from being swallowed up by the secular society around him. One who sits in the beis hamidrash all day, or who lives in Bnei Brak or Meah Shearim, doesn’t really need all such extra chumros or harchakos; he’s nowhere near the secular world.

The same word (“vayichan“) which indicates that Yaakov acted in accordance with the concept of “toshav” (a regular citizen of the world), has the additional connotation of drawing the lines for isolation through techumin. We all have an obligation to strike a proper and reasonable balance between our status as geir and toshav; and the more one functions as a toshav, the more that individual must personally emphasize that he is at the same time really a “geir.”

Rabbi Hershel Schachter joined the faculty of Yeshiva University’s Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary in 1967, at the age of 26, the youngest Rosh Yeshiva at RIETS. Since 1971, Rabbi Schachter has been Rosh Kollel in RIETS’ Marcos and Adina Katz Kollel (Institute for Advanced Research in Rabbinics) and also holds the institution’s Nathan and Vivian Fink Distinguished Professorial Chair in Talmud. In addition to his teaching duties, Rabbi Schachter lectures, writes, and serves as a world renowned decisor of Jewish Law.