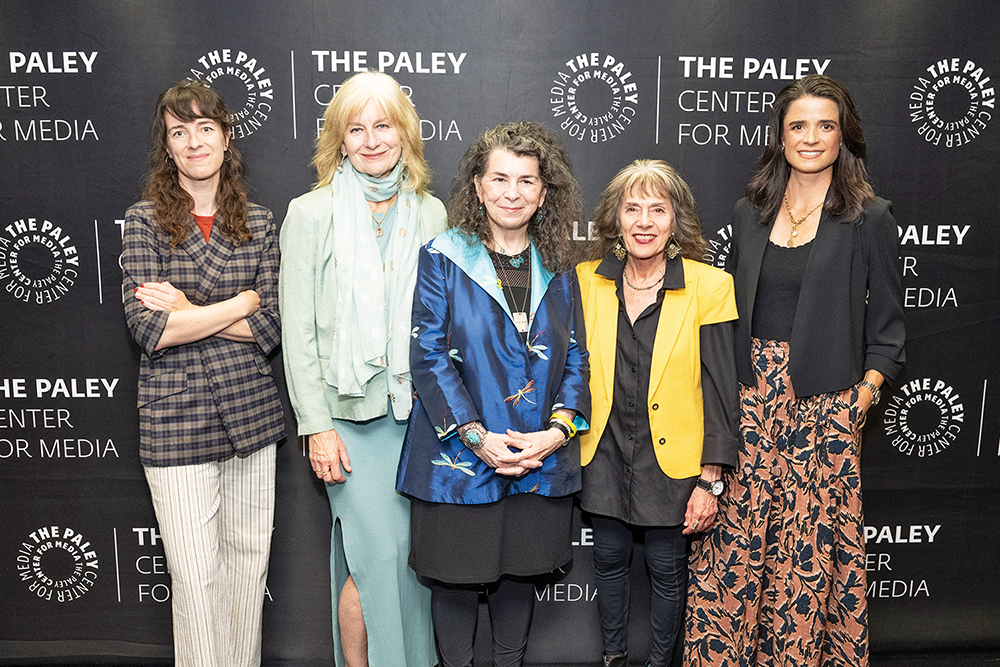

(Credit: Paley Center for Media)

Can Holocaust media combat antisemitism? On June 25, Paley Center’s Paley Impact panel on Preserving Survivors’ Legacies through Holocaust Stories, moderated by Columbia professor Annette Insdorf, grappled with that question. Panelists Georgia Hunter (We Were the Lucky Ones, 2024), Susanna Fogel (A Small Light, 2023), Aviva Kempner (A Pocketful of Miracles, 2023), and Heather Dune Macadam (999: The Forgotten Girls, 2023) discussed their Holocaust narratives’ challenges and impact. Overlapping themes and profound insights emerged.

Cross-Genre Challenges

For Hunter, turning a 416-page book into eight episodes, encompassing nine years and multi-continent Kurc family sojourns, represented a major challenge. The granddaughter of lead character Addy Kurc (played by Jewish actor Logan Lerman), she first learned about her family’s Holocaust-laden heritage during a high school history project and began recording relatives’ stories. Hunter, committed to honoring and doing justice to their legacy, hoped her children would relate to it. She praised the “incredible research drive” and “magic” in the screenwriters’ adherence to the truth.

Heather Dune Macadams’ 450-page book became the outline for 999: The Forgotten Girls, about the first official transport to Auschwitz. In March 1942, nearly 1000 well-groomed, unmarried Czech Jewish teenagers and young women, ostensibly headed for factories to support their families, were deported to Auschwitz. Despite typical teen behaviors and rivalries, this supportive “sorority of survival” helped some of them endure for three-plus years until liberation. Their voices augment the film’s passion. “I want you to feel like you’re sitting next to them, like I did,” Macadams said, “and hearing their voices, holding their hands.”

Hidden Holocaust Histories

Forty-four years after finishing “Partisans of Vilna,” Aviva Kempner filmed A Pocketful of Miracles: A Tale of Two Siblings, about her mother’s (Helen Ciesla Covensky) and uncle’s (David Ciesla Chase) Shoah stories. Why only now? What challenges existed? Kempner’s age (77), her family’s Shoah Foundation testimonies (She thanked Spielberg for these and for Schindler’s List, as a groundbreaking Holocaust film) and rising antisemitism were factors. In 2021, working on Ben Hecht’s story, Kempner encountered Holocaust denial, but never imagined today’s antisemitism. “…The expression, ‘go back to Poland’ is nauseating…and… you know, you gotta go personal.”

One commonality between documentarian Kempner’s and novelist Hunter’s family histories is their relatively recent discovery. Kempner, born in Germany, only minimally knew her family’s background. Until her mid-teens, Hunter knew nothing about her Jewish and Holocaust history. To move forward, some survivors feel they must leave parts of their past behind. David Ciesla became David Chase. Addy Kurc became Eddy Courts. Was it wrong to shield their families from the truth wrong if it increased resilience? No one can judge them. Rescuers also suppressed aspects of themselves to aid others.

Georgia Hunter. (Credit: Paley Center for Media)

Rescuers’ Resilience

During COVID, Susanna Fogel sought to justify art as meaningful. She explored Miep Gies’ sacrifice in hiding and sustaining Anne Frank’s family for years and directed episodes 1-3 of A Small Light. Why these, and why Miep? Husband and wife screenwriters Tony Phelan and Joan Rater brought their 20-something son to the Anne Frank Museum, and wondered how Miep, 20-something during WWII, could do what their son could not. After extensive research, but lacking a script, Phelan and Rater relied on Fogel’s fresh approach to Miep’s feistiness, defiance, and caustic humor within a high-stakes situation. Fogel knew that as an entrée to Frank’s iconic story, “some invention (with Miep, played by Jewish Bel Powley) could happen”

Insdorf noted how rescuers, perpetrators, and victims intersect in Holocaust stories. Can this intersection increase understanding of what triggers antisemitism? Do creatives see visual media as a tool to combat it?

Creatives’ Perceptions-Can Their Stories Counter Antisemitism?

Hunter finds today’s antisemitism climate “heartbreaking and terrifying, but:

“None of us…would think of it as a tool…we try to tell the story of one family through their eyes…in the moment, living history…The cast would say that they have to keep reminding themselves that they didn’t know how things would end. In doing that, you allow viewers to relate in a way which feels real…you can take away whatever you will.”

In conveying the Kurc family’s unique story, steeped in separation, suffering, and yet survival, “No one was trying to tell a lesson by any means or make any sweeping statements but here we are and here’s a story … and…it’s impossible not to draw parallels” with today’s situation.

Hunter’s excitement that young people and families are watching the show is augmented by numerous requests to speak in schools. It’s an opportunity to reach younger audiences unaware of the Holocaust, who might think, “that could be me.” “Until you step into the shoes and hearts and minds of someone who went through it, you can’t empathize,” and she hopes empathy will emerge among viewers.

For Macadam’s survivor Rena Kornreich Gelissen (of Rena’s Promise and that first transport), antisemitism and hate do not exist. “To hate,” Rena insists, “is to let Hitler win.” Macadam, of the same mindset, hopes that by reaching out to young people and having them relate to Rena, a light will go on. “Then you start seeing empathy…you stop seeing ‘them’ and start seeing ‘Us.’ That, I think, is the mission of the arts.”

Kempner underscores her mother’s and uncle’s “chutzpah’ and resilience—her art and his business acumen and extensive philanthropy. Such positive role models should diminish antisemitism, but Kempner insists that her re-edited film about Hank Greenberg is the best way to teach people about it. When Father Coughlin broadcast hate, Henry Ford distributed The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, and Jews were vilified during rallies, Greenberg hit a home run. That’s why she is re-releasing the film now and organizing rallies in DC to bring home the hostages. “If there’s anything I learned from the Holocaust, it’s that we all have the right to live…”

Fogel alluded to A Small Light’s impact and circled back to Phelan’s and Rater’s mission–to show Miep’s full personality, to “…drop people into the humanity of the characters and show them as complex people…a gentile woman…making a humane decision…not from…politics, but just from the heart.” In the Holocaust, ordinary people could choose to ignore or respond to events. In Amsterdam, at one time, Fogel posits, people were saying, “Is it really that bad?” We can relate to this now, when people might ask, “When’s the panic button time?” Is history repeating itself?

“The show’s writers wanted to show a woman who could not look away…how small decisions can make big differences…we have to decide how much we’re going to help other people or not. It’s ultimately a story for our lives…(one) that connects…helps us to fight antisemitism and discrimination of any kind.

One hopes that Center Programming Director Diane Lewis’ opening comments will ring true: “Amid the rising tide of antisemitism, Holocaust narratives endure as a stark reminder of the dangers of unchecked prejudice and can inspire an audience to promote tolerance.”

Rachel Kovacs is an Adjunct Associate Professor of communication at CUNY, a PR professional, theater reviewer for offoffonline.com—and a Judaics teacher. She trained in performance at Brandeis and Manchester Universities, Sharon Playhouse, and the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. She can be reached at mediahappenings@gmail.com.