In last week’s column, I mentioned that Rabba and Rav Yosef, third-generation Amoraim who each presided over Pumbedita academy, often argued with one another. A statement in Gittin 74b, וְהָא קַיְימָא לַן הִילְכְתָא כְּווֹתֵיהּ דְּרַבָּה, was taken by Tosafot as a blanket endorsement of Rabba over Rav Yosef, since it didn’t say בְּהָא as it said about a different authority. I objected: Some manuscripts had בְּהָא, and the uncharacteristic placement of Rav Yosef before Rabba suggested, with manuscript support, that this was actually an endorsement of Rava over Rav Yosef. Still, Rabba may still win the day, in general.

On Kiddushin 7b, a man betrothed a woman by giving her שִׁירָאֵי, silk. Rabba says that this silk doesn’t require appraisal; Rav Yosef says it does. The Talmudic Narrator proffers two explanations for Rav Yosef’s requirement, either that the man quotes her an accurate valuation but she doesn’t trust it, or that even if they don’t care about the value, so long as it’s a perutah, since it is shaveh kesef (something worth money) operating like kesef, just as kesef must have a fixed value, so must the shaveh kesef. A third alternative I elaborate upon elsewhere is that the Sassanian capital, Ctesiphon, was a terminus on the Silk Road, and certain items on the Silk Road, such as spice bags in Antioch, had an established trading value that they were effectively kesef (Ketubot 67a). Regardless, on Kiddushin 9a, we encounter וְהִלְכְתָא: אֵינָהּ מְקוּדֶּשֶׁת. וְהִלְכְתָא: שִׁירָאֵי לָא צְרִיכִי שׁוּמָא. וְהִלְכְתָא כְּרַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר, וְהִלְכְתָא כְּרָבָא אָמַר רַב נַחְמָן. These are rulings for several disputes, namely the most recent one on 9a, then 7b, 8a, and 8a-b.

Why Bother Ruling?

The second ruling, about silks like Rabba, bothers Tosafot (d.h. והלכתא). Why mention this if there’s a general principle, stated in Bava Batra, that the halacha’s like Rabba except for “field, matter and half”? Some suggest that principle only refers to disputes in Bava Batra, not elsewhere. Tosafot reject this based on the more comprehensive statement in Gittin 74b which I discussed last week. They admit my first point: some texts have בְּהָא for Rabba. Even so, why describe the position (שִׁירָאֵי לָא צְרִיכִי שׁוּמָא) rather than the person (Rabba), as in the next two vehilchetas? Therefore, Rabbeinu Tam says that silk is deliberately specified. While Rabba maintains nothing requires appraisal, this ruling is that particularly silks need no appraisal. Their valuation is somewhat known, so any error will be relatively insignificant. However, other items such as precious gems, where some are only somewhat valuable and it’s common to massively mistake their value, require appraisal, since otherwise she won’t rely on its stated value. That’s why the common practice is to betroth with unadorned rings. Alternatively, because Rav Yosef gave such persuasive proofs to his position here, we’d imagine this an exception to the general rule, so we state the halacha is like Rabba.

To respond to Tosafot’s points in order: This general principle appears only in Bava Batra, about cases in Bava Batra, it’s indeed limited to that tractate. When Gittin 74b notes the halacha’s like Rabba, some texts have בְּהָא. Also, there’s a manuscript and sequence-based argument that Rava is intended, not Rabba.

Further, that Bava Batra rule isn’t precisely that the halacha’s like Rabba except for three cases. Rather, it’s that the halacha’s like Rav Yosef in those three cases (one against his student Abaye). It’s an assumption of מִכְּלַל הֵן אַתָּה שׁוֹמֵעַ לָאו, based on the “yes” cases, we infer that every other case is a “no,” and rule like Rabba. And, to be terse, it listed the few exceptions, rather than many cases where Rabba wins. However, the choices here aren’t binary, for perhaps the other cases are unresolved. Or, as I suggested in my article regarding ruling like Abaye in ya’al kegam (“Abaye Seldom Wins” June 29, 2023), perhaps this invocation of the three cases is not a statement for halachic decisors, but for the Garsan, the Oral Reciter of the the Gemara in the academies, a sort of late masoretic note of where the Talmud had included a statement of וְהִלְכְתָא. In other cases, if the decision wasn’t explicit in the Talmudic text, it wouldn’t be enumerated in the list.

Why list Rabba unnecessarily? Consider the וְהִלְכְתָא sequence, addressing disputes in 9a, then 7b, 8a and 8a-b. The 9a was resolved as אֵינָהּ מְקוּדֶּשֶׁת, a position rather than name, since its shorter than saying רַב סַמָּא בַּר רַקְתָּא. Also, it addresses the immediately preceding dispute. A Talmudic Narrator then decided that while he’s reciting halachic resolutions, he may as well address others, so jumps back to 7b and covers each dispute in order. Even if explicitly ruling like Rabba is unnecessary, it might be drawn along with the others. Regarding stating the position rather than “Rabba,” it’s quite a jump back, so it might be unclear. Further, Rabba described a derasha mechanic (בָּא זֶה וְלִמֵּד עַל זֶה), not a position, in Kiddushin 4a, with Abaye arguing, so just “like Rabba” might be confusing.

Blame It on the Bava Batra

In Bava Batra 114b, Rabba says one may renege on a transaction so long as they’re seated in that location while Rav Yosef says it’s so long as they’re still engaged in that topic. Rav Yosef gives supporting logic, based on a statement by his predecessor, Rav Yehuda. Rav Ashi mentions this to Rav Kahana, who debunks the proof. The Gemara concludes with: וְהִלְכְתָא כְּווֹתֵיהּ דְּרַב יוֹסֵף בְּשָׂדֶה עִנְיָן וּמֶחֱצָה, the halacha is like Rav Yosef in the field, matter and half. The “matter” case is here.

The “field” case is in Bava Batra 12b, where a son bought land bordering his father’s property. When the father died, that son asked for his inheritance adjacent to his property. Rabba gave legal force to this claim (“kofin al midat Sedom, we compel when one party gets benefit with no detriment to the other party”), but Rav Yosef objected with a counterargument why it’s unfair. There was a similar case involving two parcels of lands next to two water channels, and an heir with adjacent land. Rabba and Rav Yosef again argue in the same way. In a third case, the two parcels are next to a single channel. Suddenly, Rav Yosef is the one arguing “kofin al midat Sedom” and his student Abaye objects. In all three cases, the halacha is like Rav Yosef over his disputant (twice Rabba, once Abaye). The wording is וְהִלְכְתָא כְּרַב יוֹסֵף, not mentioning a broader principle.

The “half” case is in Bava Batra 143a. A man told his wife, “my property is given to you and your sons.” Third-generation Rav Yosef said that half the property is the wife’s, even though the man didn’t specify proportions. Rav Yosef brought a proof. His student, fourth-generation Abaye, attacked the strength of the proof and suggested it’s sufficient to receive a portion as one of the sons. Fourth-generation Rabbi Zeira II, another of Rav Yosef’s students, also attacks, but the Gemara dismisses the attack. The Gemara then concludes וְהִלְכְתָא כְּווֹתֵיהּ דְּרַב יוֹסֵף בְּשָׂדֶה, עִנְיָן וּמֶחֱצָה, invoking the broader principle.

Omitted from this list is Bava Batra 32b. A said to B, “Pay me the 100 dinar you owe me, and here is the shtar (contract) attesting to the debt.” B replied, “It’s a forged shtar.” A leaned over and whispered to Rava, “Yes, it’s forged, but I had a good shtar which I lost, so I said that I will at least hold this one.” Rabba said that we believe A, since he could have persisted in his claim that the shtar was proper. Rav Yosef said to him, “What are you relying upon? The shtar is merely a shard of clay!” To this, fourth-generation Rav Idi bar Avin says that in land, the halacha is like Rabba; in money, the halacha is like Rav Yosef. Tosafot there note that Rabbeinu Shmuel explains that there is doubt who is right, and other rules dictate who prevails in doubt; Ri however asserts that הִלְכְתָא conveys a sense of definitive pesak rather than doubt. I’d have expected this to be listed, since Rav Yosef wins in Bava Batra, but perhaps the doubt or the split decision is the reason for its exclusion. There are also manuscript variants where Rava appears—after all, he was the whisperee—but that shouldn’t bar inclusion, since a dispute with Abaye was included.

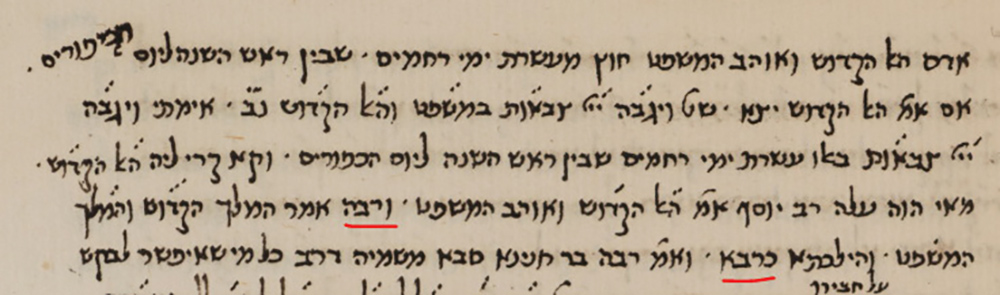

Outside Bava Batra, there’s Chullin 46b, והלכתא מגין כדרב יוסף דאמר רב יוסף… This wouldn’t be included because it’s ruling like either Rav Acha or Ravina, on the basis of Rav Yosef’s statement. There’s also Berachot 12b, where Rav Yosef and Rabba argue about certain blessing during the Ten Days of Repentance, with Rabba saying ״.הַמֶּלֶךְ הַקָּדוֹשׁ״ וְ״הַמֶּלֶךְ הַמִּשְׁפָּט״ We rule like Rabba. Why bother explicitly ruling like Rabba if it’s a general rule? Well, their positions align with earlier authorities, which may change matters. Also, like Gittin 74b, Berachot atypically has Rav Yosef before Rabba, despite Rabba ruling Pumbedita first. Some manuscripts (St. Petersburg, Paris 671 in the והלכתא, and Oxford 366) have Rava instead, and this seems correct.

Ultimately, I’m unpersuaded that this general rule like Rabba exists, or exists outside Bava Batra. I’d consider it more as a ruling, or rather mnemonic, that in these three cases we do rule like Rav Yosef. In every other sugya, we should weigh the evidence to decide for ourselves, or else treat it as a doubt.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.

1 See https://scribalerror.substack.com/p/pumbedita-and-the-silk-road