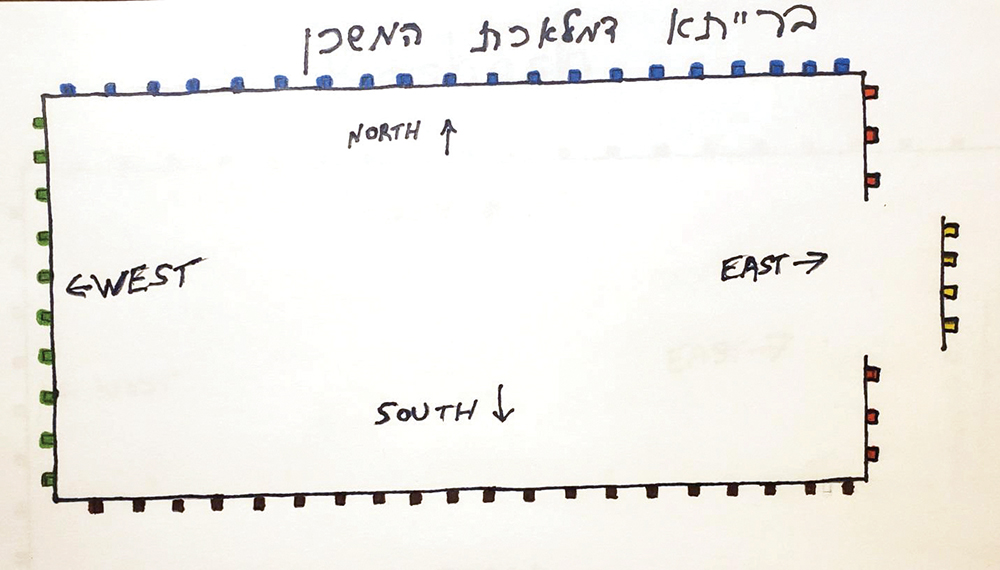

Last week, I discussed three possible solutions to the math problem presented by the location of the pillars on the perimeter of the Mishkan. In short, everyone seems to accept that there were five אמות between pillars, even though the Torah says the northern and southern sides had 20 pillars and were 100 אמות long, which would add up to only 95(אמות 19) spaces of five אמות each. Abarbanel and Malbim suggest that the five אמות did not include the width of the pillars themselves. The commentators on Rashi say there were 21 pillars (and therefore 20 spaces), with the 21st pillar also being the first pillar of the adjacent side. מעשה חושב, based on ברייתא דמלאכת המשכן, has each five-אמה section centered on a pillar, so rather than multiplying five by 19, it is multiplied by 20. This week, I’d like to focus on how Rashi dealt with the issue.

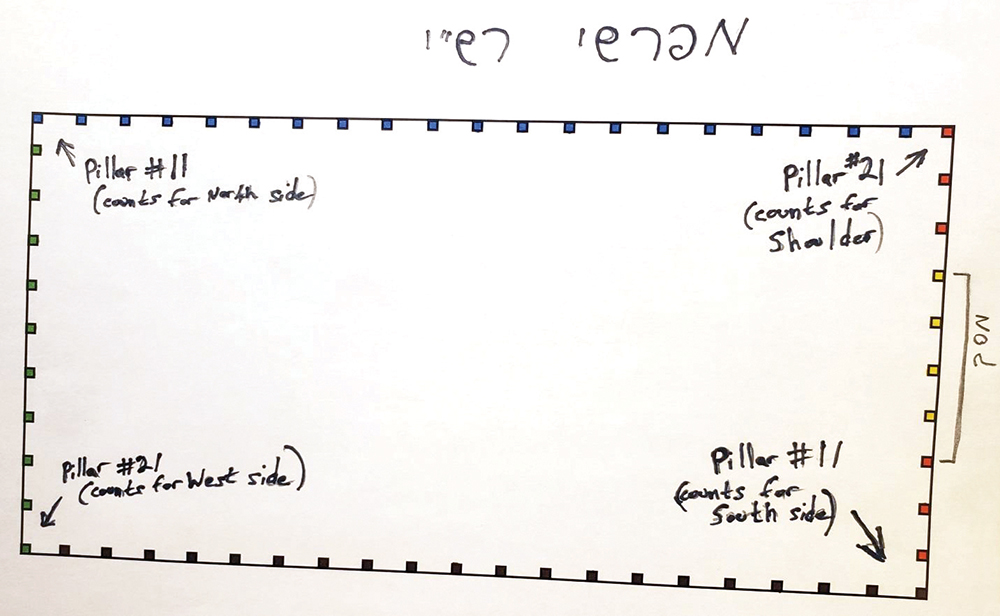

The approach of Rashi’s commentators doesn’t seem to be consistent with Rashi’s commentary. First of all, the way they describe it, the 20 pillars on the southern side start in the southeastern corner, with the 21st pillar on that side being the first of the 10 pillars on the western side. As we go around the courtyard, the 11th pillar on the western side is the first pillar of the northern side, and the 21st pillar of the northern side is the first pillar of the northern shoulder. However, Rashi (Shemos 27:14) implies that the pillar in the northeastern corner is the first of the 20 pillars on the northern side, not the first pillar of the northern shoulder. This might sound (if the pillars were inside the קלעים) like semantics, as all that really matters is that the numbers work (and some suggest that each of the corner pillars count as half-a-pillar towards each of the two sides they are adjacent to), but Rashi seems to have 12 pillars on the east side (two for the corners, six for the shoulder-three for each one- and four for the doorway), not 10.

Secondly, according to these commentators there are five אמות between every two pillars around the entire courtyard, yet Rashi only gives us the measurements for the northern and southern sides (27:10) and for the shoulders (27:14). Why mention only these sections if it applies to the entire perimeter? Additionally, Rashi tells us (27:18) that the height of the קלעים (the linen hangings surrounding the courtyard) was five אמות, and in order to complete the rectangle (as described by these commentators), the doorway pillars need to be in line with the shoulders, which requires a 10-אמה tall מזבח (altar), which in turn requires the קלעים to be 15 אמות tall, not five(see Malbim on 27:16). Besides, Rashi’s wording (27:13) strongly implies that the מסך (the screen covering the entrance of the Mishkan) was not directly between the shoulders, but parallel to it, so the rectangle was not closed, thereby preventing a shoulder pillar from supporting the מסך, and a מסך pillar from supporting a shoulder.

If Rashi understood the layout the way Abarbanel does, why didn’t he mention that the pillars themselves didn’t count towards the five אמות, or that the five-אמה measurement he gave for the south side didn’t include the pillars while the five-אמה measurement for the shoulders did? His silence about the varying width of the spaces (with those on the western side being less than 5 אמות while those of the מסך being more than five אמות) and/or the pillars (if those on the west were twice as wide as the others) also indicates that he didn’t follow this approach.

Rashi describes pillars in the corners (27:14), unlike ברייתא דמלאכת המשכן, so even though he quotes some of the things this ברייתא says, he cannot be following its approach. Besides, if that was his opinion, why did he use a different definition of קלעים than the ברייתא?

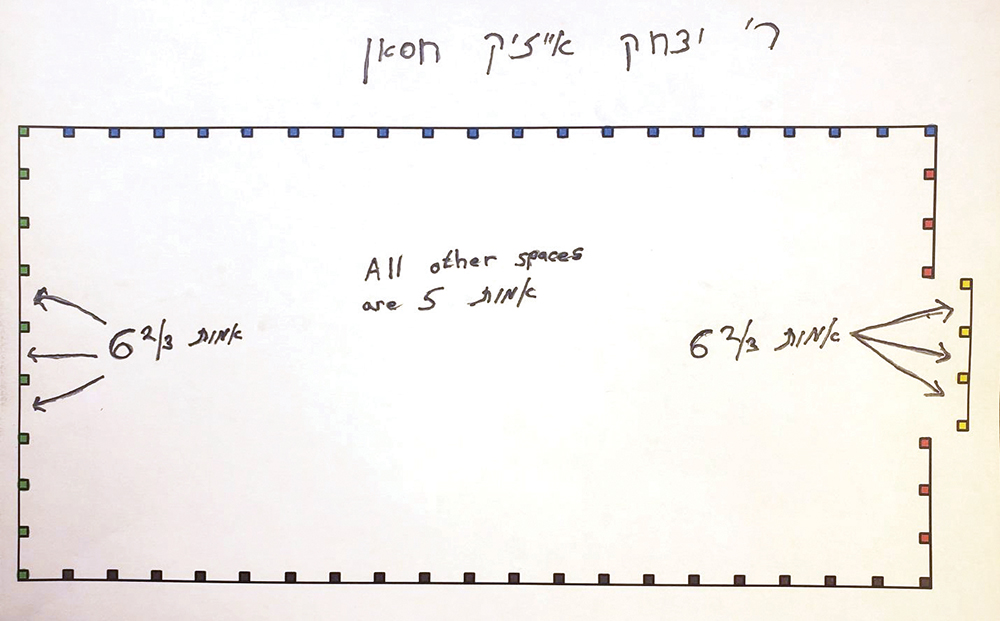

Several years ago, ר’ יצחק אייזיק חסאן published a pamphlet suggesting a fourth approach. His key was symmetry, especially of the pillars on opposite sides of the courtyard from each other. Both the northern and southern sides had 21 pillars, but the 21st pillars (of both) count towards the 10 pillars of the western side. To compensate for the missing space on that side (since 10 pillars provide only nine spaces), the middle three spaces are 6 2/3 אמות each, corresponding to three larger spaces in the מסך on the eastern side. All of the inconsistencies between Rashi’s commentary and the other approaches are gone, although I would have expected Rashi to point out that whereas every other space is five אמות, those three spaces on the western side and the spaces of the מסך were 6 2/3 אמות. Additionally, with so much emphasis on symmetry, especially when the word “כנגד” (corresponding) is used (as Rashi does in 27:14), the 10 pillars attributed to the western side should correspond exactly to the 10 pillars attributed to the eastern side. Yet, the two western corners are opposite the eastern corners (which are attributed to the northern and southern sides, not the eastern side), and the two innermost pillars of the shoulders have no corresponding pillars on the western side.

I would also point out that even though all the other spaces are exactly five אמות, most of them include just one pillar (meaning that—assuming each pillar is one אמה wide—there are four אמות between pillars), while four of the spaces—the two innermost spaces of the shoulders and the western-most spaces of the northern and southern side—include two pillars (so there are only three אמות between pillars). Additionally, of the six spaces that are 6 2/3 אמות, each of the outer four include one full pillar and one half pillar (so there are 5 1/6 אמות between pillars), while the two center spaces include two half-pillars (so there are 5 4/6 אמות between pillars).

The approach that is most symmetrical and the most straightforward, is that of ברייתא דמלאכת המשכן, with its only drawback being how the קלעים stayed up in the corners (and on the open ends). However, the Torah doesn’t describe how the קלעים were attached to the pillars. Betzalel used his «wisdom, understanding and knowledge» (31:3 and 35:31) to build the Mishkan, including how to attach the קלעים to the pillars. We can be confident that he figured out how to keep them up in the corners too. Whether (as some suggest) he used poles that lay across the hooks at the top of the pillars or some other means, not knowing with certainty how it was accomplished doesn’t mean that it wasn’t accomplished, and it certainly doesn’t mean having to abandon the layout that is (otherwise) the likeliest option.

Rabbi Dov Kramer wrote a weekly dvar Torah from 5764-5776, most of which are archived at RabbiDMK.wordpress.com and AishDas.org/ta. His Jewish Geography pieces are available at dmkjewishgeography.wordpress.com.