Did Rav Achai Gaon (author of the She’iltot, 8th century, who was associated with Pumbedita Academy but was passed over in favor of Rav Natronai Gaon) have his positions recorded in the Talmud? According to Tosafot (Ketubot 2b), Rashbam takes note of the unique language used to introduce Rav Achai’s contribution, “פָּשֵׁיט רַב אַחַאי” and “פָּרֵיךְ רַב אַחַאי”, and therefore thinks this is a late Sage, namely Rav Achai Gaon, who authored the She’iltot, who was at the end of all the Amoraim. According to Tosafot (Zevachim 102b), Rashbam further explains that this Rav Achai (missing “Gaon”), who authored the She’iltot, was of the Savoraim who followed Ravina and Rav Ashi, added hora’ah (ruling) and afterwards wrote his words at the end of the Talmud. As we’ll see, Tosafot rejects Rav Achai as a Gaon or Savora, based on our sugya (Ketubot 2b).

To expand upon Rashbam’s idea, we can often distinguish between the words of Amoraim and the “Stammaic” Talmudic Narrator on both stylistic and linguistic grounds. The Narrator writes in Aramaic and has a particular systematic approach. We might debate the dating of the Stamma —whether it is Ravina/Rav Ashi, later Savoraic redactors, or possibly even Geonim.

Meanwhile, Rav Yehudai Gaon (8th century, who headed the Sura academy) sometimes has his words inserted into the Talmud. Some Rishonim note that a lengthy passage and analysis in Bava Metzia 3a is from Rav Yehudai Gaon; similarly, in Bava Metzia 98a, manuscripts have “פירוש” before “משכחת לה”, and according to Ramban and Ritva, until the end of the passage is from Rav Yehudai Gaon.

Picture how this could work: Rav Yehudai Gaon has the written Talmud, and he (or a scribe) records his commentary, either on the margins, or after a paragraph of Talmudic text, with the word פירוש to indicate that it is commentary. When the next scribe copies it, he brings the commentary into the main body of text, or omits the word פירוש. A good analogy for this initial stage could be the Rif and Rosh, who embed their commentary together with excerpts of the Gemara, rather than Rashi and Tosafot, whose commentaries appear on the side. (Alternatively, Rav Yehuda’s commentary initially stood alone, but a scribe copied relevant sections into a Talmudic text.)

Rav Achai’s commentary might feature similarly, as a layer of commentary. He reacts to the Talmudic text, and explains, refutes and resolves. It wasn’t intended as an edit to the Talmud, but is always introduced with signature language—attribution to Rav Achai, and פָּשֵׁיט ,פָּרֵיךְ and מְשַׁנֵּי (see Ketubot 10a for the last)—and reacts to the Talmudic sugya.

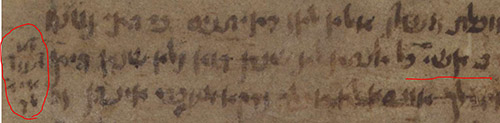

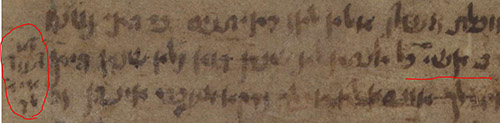

These sections can be obscured by scribal processes. For instance, in some sugyot, Rav Achai is wrongly copied as Rav Acha, e.g. Yevamot 46a, with פָּרֵיךְ רַב אַחָא (where manuscripts such as Munich 95 have אחאי). Plain Rav Acha is sixth/seventh-generation Amora and Rav Acha bar Rava is a contemporary and frequent disputant of Ravina II—both students of Rav Ashi. Or, in Bechorot 6a, while we have “פָּרֵיךְ רַב אַחַאי,” Rashi (with his dibur hamatchil) has מַתְקִיף לָהּ רַב אַחָא“,” where both the name and the unique verb have been changed.

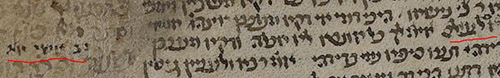

Tosafot objects to the Rashbam’s identification of Rav Achai as an extremely late figure, because in our sugya, Ketubot 2b: “שהרי כאן רב אשי עונה על דבריו”, for here, Rav Ashi responds to his words! That is, “אָמַר רַב אָשֵׁי לְעוֹלָם אֵימָא לָךְ כׇּל אוּנְסָא לָא אָכְלָה.” This Talmudic sentence tags Rav Ashi, is formulated as a response to Rav Achai’s ideas, and includes “I will say to you,” which could be the reader or could be Rav Achai.

Tosafot further dismisses the unique introductory language, noting that certain Amoraim also have relatively unique signature verbs. Rabbi Abahu ridicules in several places (מגדף; Sanhedrin 3b, 40b; Zevachim 12a; Shabbat 62b; Kiddushin 71b); Rabbi Yochanan is astonished (תהי בה; Bava Kamma 112b; Bava Batra 39b; Bechorot 42b; Kiddushin 55b; Ketubot 107b); and Abaye curses (לָיֵיט עֲלַהּ; Berakhot 29a; Taanit 29b; Shabbat 120b; Kiddushin 33b; Pesachim 104a; Moed Katan 12b; Niddah 20a). Unique language thus doesn’t necessitate that a passage is post-Talmudic. We might counter that these verbs are infrequently employed by other Amoraim, e.g. Rabbi Chanina (Avodah Zara 43b) and Rabbi Yirmeyah (Avodah Zara 35a) ridiculing. Furthermore, it’s not the unique language by itself, but coupled with final reactive opinions that suggest this.

Rav Aharon Hyman, in Toledot Tannaim va’Amoraim, believes there must be scribal error in Rashbam, for Rashbam couldn’t think that an 8th-century Gaon, author of the She’iltot and contemporary to Rav Natronai, is reckoned among the Savoraim. Rather, an errant student saw Tosafot mention Rav Achai and inserted “הגאון שעשה השאילתות,” unaware that there were two Sages named Rav Achai, one among the early Savoraim, and the other a Gaon. Hyman adds that there were two Savoraic Rav Achais, namely bar Rav Huna and bar Rabba, who were students of the Savora, Rabba Tosefa’a, and these were intended by Rashbam and they always react and explain earlier strata. Tosafot’s question still stands, for Rav Ashi shouldn’t interact with them. Hyman refers us to Tosafot on Chullin 2a, s.v. אנא, where Rav Ashi frames the question, yet Abaye and Rava seem to react to it. They answer that Abaye and Rava grappled earlier with the same question, and their answers were incorporated. So too in Ketubot, Rav Ashi could have grappled with something Savoraim also grappled with, but didn’t interact directly.

Personally, I’m happy with some Stammaic material even extending to Geonic times. After all, we have Rav Yehudai Gaon’s occasional contribution. Rashbam could label Rav Achai Gaon a “Savora” by virtue of post-Rav Ashi contribution to the main Talmudic text. As for the apparent interaction with Rav Ashi, we should consider manuscript evidence. Firstly, attribution to Rav Ashi is absent in quite a number of manuscripts, including Vatican 130, and in Munich 95, “ רב אשי אמר” appears as a marginal gloss. A scribe could add attribution to Rav Ashi, the Talmud’s redactor, to distinguish it from Rav Achai’s commentary. Also, Rav Steinsaltz notes that “לְעוֹלָם אֵימָא לָךְ” is absent in several sources, and indeed, in the Cologne manuscript, it appears as a marginal gloss. Thus, aside from the Talmudic arrangement which creates a misimpression of the interaction of Rav Achai and Rav Ashi, it’s plausible that this is all Stammaic material.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.