This week we explore how biographical knowledge can help us with punctuation.

Sukkah 4b informs us that several Sages taught the same proof that a sukkah must exceed 10 handbreadths. Namely, we can calculate based on biblical verses that the Ark of the Covenant with its cover was 10 handbreadths, and in a beraita, Rabbi Yose (b. Chalafta, a fifth-generation Tanna) establishes that God never descended below. Thus, only from 10 handbreadths and up is considered a separate domain.

The attribution to these Sages is given as:

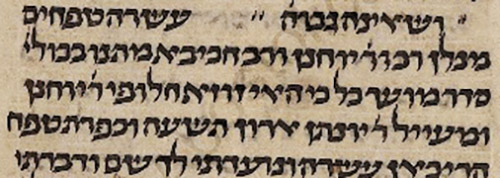

אִתְּמַר רַב וְרַבִּי חֲנִינָא וְרַבִּי יוֹחָנָן וְרַב חֲבִיבָא מַתְנוּ. בְּכוּלֵּהּ סֵדֶר מוֹעֵד כָּל כִּי הַאי זוּגָא חַלּוֹפֵי רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן וּמְעַיְּילִי רַבִּי יוֹנָתָן.

“It was stated (by Amoraim): Rav (Rabbi Abba b. Aivo, first-generation Amora who descended from Israel to Babylonia), Rabbi Chanina (b. Chama, first-generation Amora who ascended from Babylonia to Israel), Rabbi Yochanan (second-generation Amora of Israel) and Rav Chaviva taught it. In the entire Order of Moed, in each instance of this (second) pair, replace Rabbi Yonatan (b. Eleazar Ish HaBirah, first-generation Amora who ascended from Babylonia to Israel) for Rabbi Yochanan.”

Substituting in Rabbi Yonatan makes sense since, like the others, he is an emigrating first-generation Amora. The error could arise because Rabbi Yochanan is more famous, Yochanan sounds like Yonatan, and when written, chet looks like tav. A substitution and transposition of letters will transform one name to the other.

(Also noteworthy is that the Oxford 366 and Vatican 134 transpose the list such that Rav and Rabbi Yochanan appear at the start of the list; that Vatican 134 omits Rabbi Chanina so there are only three names; and that a nun looks like a bet such that ר’ חביבא is an easy substitution for ר’ חנינא—see Dikdukei Soferim to Bava Metzia 61b where this error occurred. Also חנן is found in both Rabbi Chanina and Rabbi Yochanan, so potential scribal errors, including duplication, abound.)

This parsing of the attribution is found in Tosafot (Shabbat 54b), that the Talmudic narrator rules for us to make this substitution throughout Seder Moed. Rashi explains similarly that nameless Amoraim make this substitution.

However, who is Rav Chaviva? A seventh-generation Amora, of Sura on the Euphrates River, he poses questions to Ravina, especially when Ravina visits his hometown (Moed Katan 20a). Ravina thought to marry his son into Rav Chaviva’s household (presumably his daughter) and confidently recited the betrothal blessings, but ultimately the wedding was canceled (Ketubot 8a). Elsewhere, we see that the nuptials were delayed from one Wednesday to the next (Niddah 66a, girsat haRif). In Chullin 51a, Ravina and Rav Yemar offer contradictory diagnoses for Rav Chaviva’s ewe who was dragging her hind legs.

As Hyman points out in “Toledot Tannaim vaAmoraim,” it is quite strange for the late Rav Chaviva to be paired with the early Rabbi Yochanan. He approvingly cites “Mishpachat Soferim” that Rav Chaviva isn’t part of the zug, but the one performing the substitution throughout Moed. Thus, in Sukkah, Shabbat and Megillah 7a, all in Moed, when the zug of [Rav, Rabbi Chanina, Rabbi Yochanan] appear, Rav Chaviva replaces the last with Rabbi Yonatan. In Chullin 108a, of a different seder, the zug appears with no replacement. Even within Moed (Eruvin 8b) with a different 3-tuple, e.g. [Rav, Rabbi Chiyya, Rabbi Yochanan], Rav Chaviva doesn’t make the substitution. I’d add that we see Rav Chaviva explicitly in this role in Shevuot 40b: the Gemara interprets Rav Nachman’s statement as pertaining to the Mishna’s first clause, but then Rav Chaviva teaches (מתני, same as above) Rav Nachman’s statement as pertaining to its latter clause.

We thus punctuate against Rashi and Tosafot, and it is a particular named late Amora whose Talmudic text reads like this. The Talmudic narrator does not “rule” for us in accordance with this emendation, and indeed might rule in accordance with the first version. For comparison, see Pesachim 120a, where there are two versions, differing in whether ain maftirin or maftirin achar hamatzah afikomen—the former anonymous and the latter by Mar Zutra. Rif/Rosh consider it logical to side with the first version, since the Gemara endorses it, while the latter is only according to Mar Zutra. (In Shevuot 40b, they also rule like the first version; Rabbeinu Tam disagrees.) This seems debatable and hinges on the dating of the Talmudic narrator and his intent in citing multiple versions generally. With several oral/manuscript versions floating around, perhaps providing an attribution gives a version greater credence.

Entering the realm of heavy speculation, should we eliminate Rabbi Chanina from the zug? While Jastrow gives “set” as one meaning of zug, it typically means a pair, not a 3-tuple. Rashi assumed two pairs by incorporating Rav Chaviva, but we only have three people. We could establish Vatican 134 as primary, in which Rabbi Chanina doesn’t appear (recalling the nun / bet confusion; however, no such variation exists in Megillah and Shabbat). The pair would then be Rav/Rabbi Yochanan. If so, is the variation in Moed only when the Gemara explicitly mentions Rav Chaviva or more generally? The repercussions are potentially earth-shattering. A general principle of psak halacha is that we rule like Rabbi Yochanan over Rav. (See Beitza 4a, in Moed.) But, what if throughout Moed, Rav is actually arguing with Rabbi Yonatan?

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.