In Sanhedrin 61a, Rav Hamnuna lost his oxen and went searching for them. Rabba bumped into him and took the opportunity to pose a contradiction between two Mishnayot, and Rav Hamnuna resolved it. Rav Yosef chimed in as to why this is unnecessary. Then Abaye, Rava, Rav Ashi and, finally, Ravina all weighed in. This is thus a diachronic (developed across time) sugya.

Which Rav Hamnuna is this?. Several Amoraim shared this name. Rav Aharon Hyman, in Toledot Tannaim va’Amoraim, discusses four. Rav Hamnuna I was a student of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi. Rav Hamnuna II was a second-generation Amora and Rav’s student. Rav Hamnuna III was from the city of Harpania and a third-generation student of Rav Yehuda, whom Rav Chisda praised to Rav Huna, after which Rav Hamnuna may have stayed a while before Rav Huna and then Rav Chisda. His colleagues included Rav Yosef and Rabba. Finally, there is fourth-generation Rav Hamnuna IV, in the days of Abaye and Rava, who Rav Hyman argues must exist, on the basis of various Gemaras involving Abaye and Rava.

I probably agree with Rav Hyman who identifies our sugya’s Rav Hanuna as Rav Hamnuna III. After all, it is Rabba who first addresses him, and Rav Yosef weighs in. These are third-generation Amoraim, heads of the Pumbedita academy. Presumably the reason we’re informed that he was searching for his oxen is to account for this Suran Amora’s presence in the vicinity of the Pumbedita academy.

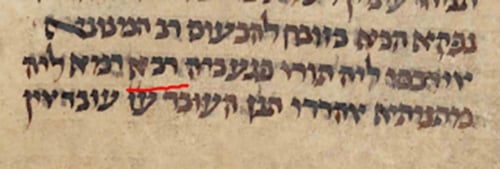

Naturally, there are variant texts — the Venice, Vilna and Barko printings, Reuchlin 2 manuscript, and the Oxford: Heb. c. 17/61–62 fragments have Rabbi meet him; Florence 8-9, Yad HaRav Herzog, and Munich 95 manuscripts have Rava meet him. If Rava, he might be Rav Hamnuna IV. Still, we have Rav Yosef react, and Rava makes a separate appearance later in the sugya.

Conflicting Mishnayot

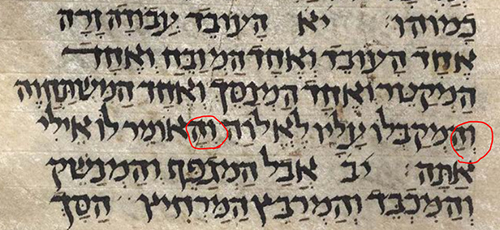

The purported conflict is that our Mishna (Sanhedrin 60b) only declares עוֹבֵד (“worships”) is liable but אוֹמֵר (“speaks”) is not. Meanwhile, a later Mishna (on Sanhedrin 67a) says that הָאוֹמֵר ׳אֶעֱבוֹד׳ is liable. This formulation seems to indicate that the distinction is between physical action / עוֹבֵד vs. mere speech / אוֹמֵר. However, a careful reading of our Mishna and ensuing Gemara could lead to a different conclusion. After all, one of the very acts of עוֹבֵד in our first Mishna is וְהָאוֹמֵר לוֹ אֵלִי אַתָּה— One who says to the idol “you are my god,” as well as הַמְקַבְּלוֹ עָלָיו לֶאֱלוֹהַּ, he accepts it upon himself as a god. Why not contrast from our Mishna itself? Therefore, the distinction seems to be between (our Mishna) being liable for speech / acceptance about the present alone vs. (later Mishna) being liable for speech only about future worship.

Regardless, this seems to be a strange conflict, as our Mishna deals with acts of worship (avodah zara) while the later Mishna’s context is incitement to idolatry (meisit). These are two separate prohibitions! Incitement to idolatry intrinsically involves speech, while idolatry intrinsically involves action. Further, incitement is present speech to encourage action in the immediate or distant future. Regardless, Rav Hamnuna resolves the contradiction, saying it (our Mishna, or perhaps that Mishna) deals with one who states: “I am only formally accepting this idol as a god through actual worship.”

Rav Yosef objected, “Have you removed Tannaim from the world? This is a Tannaic dispute! There’s a brayta: If he says, ‘Come and worship me,’ Rabbi Meir deems him liable and Rabbi Yehuda deems him exempt.”

The Talmudic Narrator explains Rav Yosef— he understands this as a Tannaitic dispute about mere speech, not speech followed by the action of actual worship. Rabbi Meir maintains דִּיבּוּרָא מִילְּתָא הִיא, mere speech is nevertheless significant, while Rabbi Yehuda maintains it’s not significant. This seems to ground the dispute about speech vs. action, which seems strange since our Mishna itself mentions הָאוֹמֵר.

Rav Yosef’s ability to recall relevant braytot is part of his signature. He was a master of oral traditions and was therefore called “Sinai,” evoking Har Sinai where the Torah was given. Meanwhile, Rav Hamnuna’s original interlocutor, Rabba, was known as the “Uprooter of Mountains,” famed for his analytical ability (Berachot 64a). Rav Yosef then retracted because he recalled yet another brayta in which Rabbi Yehuda explicitly makes one liable (for meisit) for mere speech about future idolatrous action.

Rav Yosef retracted, הֲדַר אָמַר רַב יוֹסֵף, by saying לָאו מִילְּתָא הִיא דַּאֲמַרִי, “what I said was not correct.” This is a funny way of expressing this idea. He’s saying that his previous speech was not significant! Now this is a common expression of retraction. See Rosh Hashanah 13a; Yevamot 20b; Ketubot 33a; Gittin 23a; Bava Metzia 6b, 131a; Makkot 8a, 8b; Zevachim 94a; Menachot 12b, 35b and 97a. It’s sensible to say this joke arose from random chance and the requirements of the sugya. Still, I believe that, in general, there’s a Talmudic phenomenon of lashon nofel al lashon, “an expression falls on another expression,” but not as deliberate wordplay. Instead, it is psycholinguistics where a word “primes” the author to employ the same or similar sounding word later.

If we could go against the Talmudic Narrator’s framing as speech vs. action, then perhaps Rav Yosef initially saw בּוֹאוּ וְעִבְדוּנִי as reckoning himself in the present tense as a god (see Rashi) and asking others to worship him, so Rabbi Yehuda exempts; but the later brayta has Rabbi Yehuda only make one liable for incitement if he himself will be a participant. If so, maybe the Talmudic Narrator was primed by Rav Yosef’s language of retraction, לָאו מִילְּתָא הִיא.

Is Acceptance / Speech Worship?

I grappled above with acceptance / speech being an enumerated worship in our very Mishna. After all, the Mishna declares liable one who worships idols, saying אֶחָד הָעוֹבֵד, וְאֶחָד הַמְזַבֵּחַ, וְאֶחָד הַמְקַטֵּר, וְאֶחָד הַמְנַסֵּךְ, וְאֶחָד הַמִּשְׁתַּחֲוֶה, וְאֶחָד הַמְקַבְּלוֹ עָלָיו לֶאֱלוֹהַּ. Acceptance is included with the explicit וְאֶחָד. However, this may well be in error. In the Mishna in the Yerushalmi, as well as in the Kaufmann Mishna manuscript, it is וְהַמְקַבְּלוֹ עָלָיו לֶאֱלוֹהַּ, omitting וְאֶחָד. So too, in the Bavli, while printings as well as Yad HaRav Herzog, Reuchlin 2 and Munich 95 manuscripts have וְאֶחָד, the Florence 8-9 manuscript and Oxford: Heb. c. 17/61–62 fragment skip it.

If so, וְהַמְקַבְּלוֹ / וְהָאוֹמֵר / accepting / speaking are separate ideas, and not an example of הָעוֹבֵד / worship. The next Mishnaic phrase declares lesser liability for one who merely displays honor towards the idol, for instance by hugging or kissing it, which are not acts of worship. Are these contrasted to the physical acts above, or also to the now-interjected sentence about accepting the idol via speech? Alternatively, could וְהַמְקַבְּלוֹ / וְהָאוֹמֵר be intended to specifically modify the bowing, akin to Abaye’s analysis of liability for bowing at the bottom of Sanhedrin 61b?

Tosefta Sanhedrin 10:2 has similar language as our Mishna, with elaboration via וְאֶחָד but with הַמְקַבְּלוֹ / הָאוֹמֵר at the end of the list without וְאֶחָד, all liable to sekila. A bit later, when contrasting with hugging and kissing, it states that one’s only liable to bring a korban על דבר שיש בו מעשה, and again provides the list, this time without acceptance / speech.

It seems possible that there’s some Tannaitic dispute here. Sanhedrin 63a discusses this Mishnaic phrase of הַמְקַבְּלוֹ / הָאוֹמֵר and quotes Rav who says the same. The Mishna might be discussing deliberate action / sekila while Rav was discussing quasi-accidental action / korban. Reish Lakish suggests that this is a Tannaitic dispute, and it is specifically Rabbi Akiva who maintains that mere bowing — and by extension, mere speech — makes one liable. Similarly, at the close of Yerushalmi Sanhedrin 7:9, analyzing the Mishna’s הָאוֹמֵר לוֹ אֵלִי אַתָּה, Rav Shmuel bar Nachmani quotes Rabbi Hoshaya that this is a dispute between Rabbi (Yehuda HaNasi) and the Sages. Rabbi Yochanan (an Amora) makes the mere-bowing / mere lip-movement connection. Several commentators (Ridvaz, Korban HaEida, but not Pnei Moshe) emend “Rabbi” to “Rabbi Akiva,” paralleling the Bavli. Still, I wonder if this intervening וְהַמְקַבְּלוֹ / וְהָאוֹמֵר phrase could be Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi’s splice into an existing Tannaitic text, reflecting his own opinion about the significance of speech.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.