This column’s focus is on the people who appear on the page of Daf Yomi. Often, when learning Talmud, we focus on the shakla vetarya, the give and take, and focus less on the people who present the ideas. Yet, Chazal do consider attribution important, telling us that הָא לָמַדְתָּ שֶׁכָּל הָאוֹמֵר דָּבָר בְּשֵׁם אוֹמְרוֹ מֵבִיא גְאֻלָּה לָעוֹלָם, “Whoever cites a statement in the name of the one who said it brings redemption to the world.” (This appears in the additional sixth chapter of Avot, ironically, unattributed. Elsewhere, we see this attributed to Ben Azzai and to Rabbi Eleazar ben Pedat citing Rabbi Chanina.) Knowledge of the author of a statement can give us insight into its content, help build a picture of the general halachic view of that Tanna or Amora, and sometimes has bearing on halacha.

In Yoma 70a, the gemara analyzes the Mishna on 68b, which had stated that on Yom Kippur, the kohen gadol reads three different portions from the Torah. The portions beginning with “Acharei Mot” (Vayikra 16) and from “Ach Be’Asor” (Vayikra 23) are read from the scroll. Finally, he recites by heart from “Uve’asor” from Chumash Bamidbar (29).

The Gemara:

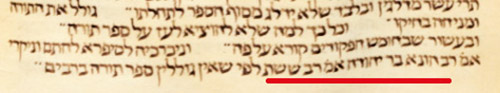

״וּבֶעָשׂוֹר״ שֶׁל חוֹמֶשׁ הַפְּקוּדִים קוֹרֵא עַל פֶּה. אַמַּאי? נִגְלוֹל וְנִיקְרֵי! אָמַר רַב הוּנָא בְּרֵיהּ דְּרַב יְהוֹשֻׁעַ אָמַר רַב שֵׁשֶׁת: לְפִי שֶׁאֵין גּוֹלְלִין סֵפֶר תּוֹרָה בְּצִיבּוּר, מִפְּנֵי כְּבוֹד צִיבּוּר

וְנַיְיתֵי אַחֲרִינָא וְנִקְרֵי! רַב הוּנָא בַּר יְהוּדָה אָמַר: מִשּׁוּם פְּגָמוֹ שֶׁל רִאשׁוֹן. וְרֵישׁ לָקִישׁ אָמַר: מִשּׁוּם בְּרָכָה שֶׁאֵינָהּ צְרִיכָה

That is, first it explores why the kohen gadol recites by heart, instead of scrolling through the scroll. Rav Huna b. Rav Yehoshua cites Rav Sheshet that subjecting the congregation to this lengthy process is not in their honor. As a follow-up, why not bring another sefer Torah that had been previously rolled to the proper place? Rav Huna b. Yehuda explains that this would falsely impugn the validity of the first sefer Torah, while Rabbi Shimon b. Lakish says that this would entail an additional, unnecessary blessing.

The attribution in the first paragraph seems strange. Rav Huna son of Rav Yehoshua is a fifth generation Amora and a frequent disputant of Rav Pappa. Meanwhile, Rav Sheshet was a third generation Amora, who lived much earlier. A citation skipping a generation is somewhat surprising, but perhaps it is via Rava, who is R’ Huna b. R’ Yehoshua’s teacher and R’ Sheshet’s student.

Meanwhile, Rav Huna b. Yehuda, in the next paragraph, is a fourth generation Amora. His teacher was Rav Sheshet and he was a talmid chaver (student/colleague) of Rava. (Rav Aharon Hyman, in “Toledot Tannaim v’Amoraim,” establishes this teacher-student relationship by listing many times Rav Huna bar Yehuda cites or interacts with Rav Sheshet, including Eruvin 26b, 89b; Yoma 25a; and more). Rabbi Shimon b. Lakish is earlier, a second-generation Amora from Eretz Yisrael. Absent other considerations, we typically expect positions in the Gemara to be laid out chronologically, so we might expect Resh Lakish first.

We immediately suspect that “Rav Huna b. Rav Yehoshua” is a scribal error for “Rav Huna b. Yehuda.” After all, the latter is the student of Rav Sheshet, and cites Rav Sheshet quite often, including earlier in our very masechet, on Yoma 25a. Many tokens overlap in their respective names, and Yehoshua and Yehuda begin with the same prefix. Rav Huna b. Rav Yehoshua appears frequently in the Talmud; Rav Huna b. Yehuda seldom appears. The situation is ripe for a scribe to incorrectly write the more frequent rabbi, or to expand an abbreviation of the name improperly.

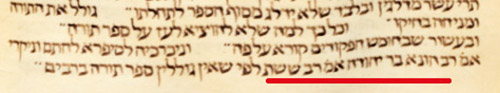

Inspecting the manuscript evidence (using the Hachi Garsinan website), several texts indeed have Rav Huna (or Chuna) b. Yehuda in the first paragraph. These include אוקספורד 366;

אנלאו 270 + 271, and מינכן 6.

It is possible that these Talmudic texts with “Rav Huna b. Yehuda” are erroneous and arose from dittography, that is, duplication of text that appears in proximity (namely, Rav Huna b. Yehuda in the next paragraph). However, I think that Rav Huna b. Yehuda throughout makes more sense.

With the fourth generation Rav Huna b. Yehuda citing his teacher Rav Sheshet as he does frequently, he resolves two questions in the Gemara, first (citing Rav Sheshet) why not roll the sefer Torah to its place in sefer Bamidbar so as to read from the text rather than orally, and second, a follow up, why not bring another sefer Torah turned to the proper place. The answer to the second question might be his own, or this could be a continuation of Rav Sheshet’s position. Rav Sheshet is closer in time to Resh Lakish. Regardless, continuing with the same Amora would override chronological considerations.

Here, knowledge of the Talmudic biographies allowed us to resolve identities in a way that was supported by some manuscript evidence. In future columns I hope to explore other ways in which this knowledge can enhance our understanding of the sugya.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.