In a recent article (“Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak, Name-Giver?,” December 12, 2024), I discussed Rav Reuven Margolios’ suggestion that Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak was responsible for many of the appellations given to Talmudic Sages, including those who were purportedly named for the singular and memorable halacha they uttered. I disagreed with that suggestion, and I’ll continue to pick fights about aspects of that analysis. Well, we’ve arrived at Sanhedrin 17b—a central sugya which serves as a dictionary between descriptive name and actual Sage. These descriptive names appear throughout the Talmud, and we’ll see Rishonim point to our sugya.

In his treatise, לחקר שמות וכינויים בתלמוד, chapter five about the Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak’s style, Rav Margolios wrote, “And Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak is the one who transmitted to us many appellations of Sages in his generation, such as our rabbis in Babylonia, the judges of the Diaspora, the judges of the land of Israel, the judges of Pumbedita, the judges of Nehardea, the elders of Sura, the elders of Pumbedita, the sharp ones of Pumbedita, the speakers (Amoraim) of Pumbedita, the speakers of Nehardea and others—see Sanhedrin 17b, and in my sefer ‘Margaliot HaYam’ there, 10-20.”

My impression of this sugya differs. The preceding segment had Rav Yehuda quote Rav that a small subset of the Sanhedrin needed to speak/comprehend 70 languages; at Beitar, there were three such individuals; in Yavneh, there were four: Rabbi Eliezer, Rabbi Yehoshua, Rabbi Akiva, as well as Shimon HaTimni (an unordained Sage) who would deliberate before the others while seated on the ground.

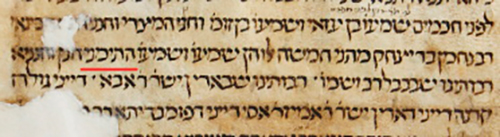

After a brief objection, this naturally leads to the next segment, which is not ascribed to any author. That segment begins with לְמֵידִין לִפְנֵי חֲכָמִים—לֵוִי מֵרַבִּי. דָּנִין לִפְנֵי חֲכָמִים—שִׁמְעוֹן בֶּן עַזַּאי, וְשִׁמְעוֹן בֶּן זוֹמָא, וְחָנָן הַמִּצְרִי, וַחֲנַנְיָא בֶּן חֲכִינַאי. רַב נַחְמָן בַּר יִצְחָק מַתְנֵי חֲמִשָּׁה: שִׁמְעוֹן, שִׁמְעוֹן, וְשִׁמְעוֹן, חָנָן, וַחֲנַנְיָה. Thus, there’s a definition of “they taught before the Sages” as Levi before Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi. “They deliberated before the Sages” is mapped to a group of four Sages—two of whom are named “Shimon,” none who have ordination and thus, lack their rabbinic title. To this, Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak reacts by adding an additional “Shimon.”

This would be Shimon HaTimni—who deliberated before the Sages—as per Rav Yehuda citing Rav. Rashi notes that this extra “Shimon” is Shimon HaTamni, and two manuscripts have HaTimni explicitly. That’s what Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak came to interject, and that’s the connection to the preceding segment. Indeed, that identification may have come from the preceding segment.

The other two Shimons may have also come from another Gemara. The opening Mishna in Horayot discusses those who aren’t members of the Sanhedrin itself but are students qualified to issue halachic rulings. In Horayot 2b, Rava identifies those such as Shimon ben Azzai or Shimon ben Zoma. Chanan HaMitzri appears as a judge in Ketubot 105a, and in Chagiga 14b, Chanania ben Chachinai lectured before Rabbi Akiva.

The section then continues with other identifications, this time of Amoraim up until the fifth generation, beginning with רַבּוֹתֵינוּ שֶׁבְּבָבֶל—רַב וּשְׁמוּאֵל. רַבּוֹתֵינוּ שֶׁבְּאֶרֶץ יִשְׂרָאֵל—רַבִּי אַבָּא. Rav Margolios presumably believes that the transition in people, from Tannaim to Amoraim, indicates a switch in author. Further, the introduction via רַב נַחְמָן בַּר יִצְחָק מַתְנֵי חֲמִשָּׁה indicates that Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak teaches these identifications.

Pumbeditan Variants

I’m not persuaded that Rav Nachman is the author. Many of the identifications—such as Rav and Shmuel—are of a much earlier generation than Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak. (As discussed in our earlier article, Rav Margolios also seems to place Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak much earlier.) Also, I’d interpret Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak’s statement as a limited interjection to what was just said, that the text listed four and he actually listed five. Afterwards, the preceding anonymous author resumed his dictionary of names.

Something we’ve discussed is what the verb מַתְנֵי means when an Amora does it. For instance, in “Rav Chaviva the Redactor” (Jewish Link, July 8, 2021), we discussed how—while the standard Talmudic recension had a triplet of Rav—Rabbi Chanina and Rabbi Yochanan throughout the order of Moed, it noted that Rav Chanina (a contemporary of Rav Ashi) taught (מַתְנו) throughout Moed with “Rabbi Yonatan” replacing Rabbi Yochanan. That is, our Talmud has a standard oral text and Talmudic narrator, but is aware of parallel oral texts and will mention those variants, giving credit to that foreign editor.

Looking through Talmud, the phrase רַב נַחְמָן בַּר יִצְחָק מַתְנֵי appears nine times—in each instance giving a variant text. Thus, in Eruvin 78b, third generation Pumbeditan Amora Rav Yosef posed two dilemmas to Rabba. The Talmudic narrator makes these questions valid, and to be explored—within the opinions of disputing Tannaim. Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak, however, makes it dependent upon the Tannaic disputes. I don’t think Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak is arguing with Rav Yosef, but presenting a different version of the shmayta1.

In Sukkah 46b, the Talmudic narrator deduces Rav’s position to recite the blessing on lulav all seven days—based on Rav’s statement about reciting a blessing over Chanukah lights. Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak, meanwhile, taught Rav’s statement directly. In Yevamot 11b, the anonymous standard Talmudic text records that Rav Chiyya bar Abba notes a dilemma posed by Rabbi Yochanan about chalitza upon a forbidden remarriage, and Rabbi Ami converses with him.2 Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak teaches a variant conversation between them. The same participants—Rabbi Chiyya bar Abba, Rabbi Yochanan and Rabbi Ami—converse in Zevachim 85b about lesser sacrificial offerings which were brought upon the altar before sprinkling of blood. Again, Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak presents a conversational variant. In Chullin 12b, again we have the same three participants, about whether a minor has halachically effective thought, and Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak presents a conversational variant.

In Ketubot 7a, the standard Talmud notes that Rabbi Yaakov bar Idi said that Rabbi Yochanan issued a ruling in the city of Tzaidan prohibiting consummating certain marriages on Shabbat. This is discussed for a while, and then, רַב נַחְמָן בַּר יִצְחָק מַתְנֵי הָכִי—Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak had a different version and attribution, in which Rabbi Avahu said that Rabbi Yishmael ben Yaakov—who is from Tyre—asked this as a question to Rabbi Yochanan when he was in the city of Tzaidan, and Rabbi Yochanan prohibited.

In Gittin 29a—with a background that an agent of delivery of a get may appoint another agent—the standard Talmud have the Sages request that Avimi, the son of Rabbi Abahu, ask his father whether this second agent can appoint a third agent. He answers the question himself but tells them to ask a different question, whether the second agent must appoint the third agent in court. The Sages explain why they don’t consider the question necessary. Meanwhile, Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak teaches a variant that flips who utters the two questions.

Finally, in Temurah 21a, Rava bar Rav Azza said they inquired in the West about one who inflicts a blemish on a temurah (replacement of a firstborn or tithed animal). These aren’t brought on the altar, so is he, perhaps, not liable? On the other hand, they are sanctified. Abaye responds that the dilemma should be raised about the ninth animal accidentally declared the tithed tenth. Once the discussion ends, Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak repeats a variant, in which the dilemmas are flipped.

These sugyot cement Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak’s role as someone in charge of proto-Talmudic variants, while presiding over Pumbedita academy. He records different shakla vetarya—Amoraic give-and-take, up to and including the fourth Amoraic generation. Compare with the internal Talmudic variants given by a later head of Pumedita, Mar Zutra.3 If so, when Rav Nachman bar Yizchak narrowly interjects in Sanhedrin, he’s not assuming control of all the descriptive name definitions from then on. By extension, this shouldn’t be used to blame/credit him with devising other descriptive names.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.

1 See also Tosafot ad loc, שירה פלוגתא דרבי יהודה ורבנן, that Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak must not have the earlier sugya of Eruvin 31a.

2 Either with Rabbi Yochanan or with Rabbi Chiyya bar Abba.

3 See מָר זוּטְרָא מַתְנֵי הָכִי six times: twice in Shabbat 129a, Pesachim 10b, Pesachim 120a, Nazir 57b, and Chullin 62b.