A Mishnah (Bava Kamma 100b) discussed a dyer who damaged wool given to him to dye. If the wool was entirely destroyed by the cauldron, he pays the full value. If he dyed it unattractively (כָּאוּר) then the wool-owner pays the dyer the minimum of the dyer’s expenses and the value of the wool’s enhancement.

What does כָּאוּר mean? In the Gemara (100b-101a) Rav Nachman cites Rabba bar bar Channa that it is כַּלְבּוֹס. And, the Gemara asks, what is כַּלְבּוֹס? Rabba bar Shmuel said כַּפְרָא דּוּדֵי, which Rashi explains as the sediments of dye in the cauldron from a previous dyeing, which he used to dye this new wool.

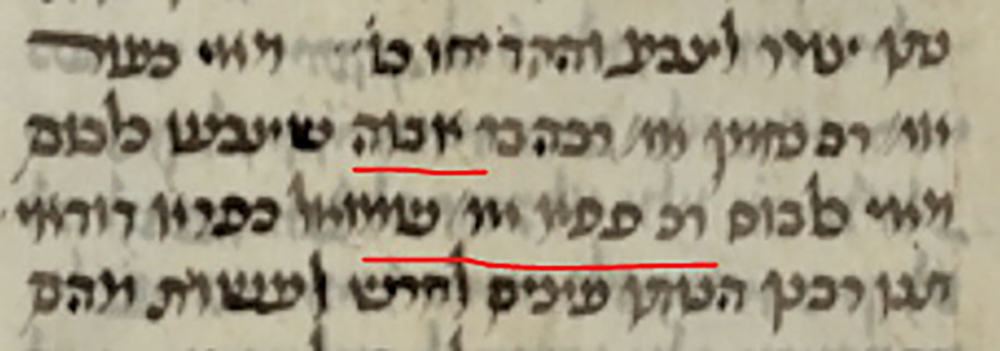

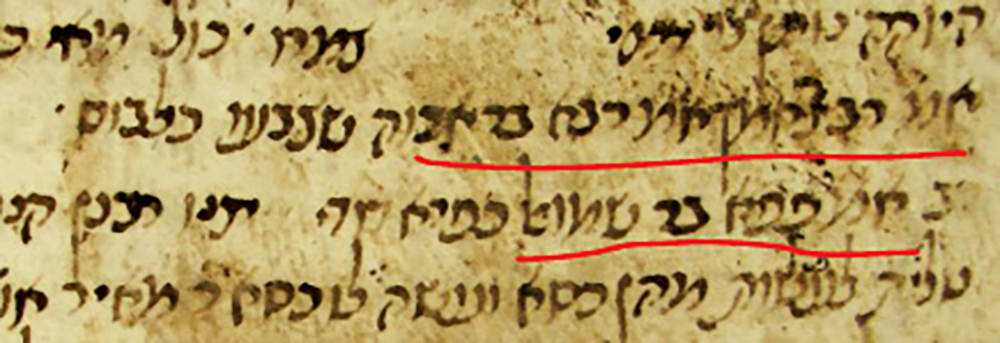

Prior to any analysis of the content, we should ensure we have the right people named. Rav Nachman bar Yaakov, a Babylonian third-generation Amora, citing an Israeli contemporary, should raise red flags. We’d instead expect him to cite his primary teacher, Rabba bar Avuah, a second-generation Babylonian Amora. Indeed, while printings (Vilna, Soncino, Venice) make this mistake, the manuscripts (Hamburg 165, Munich 95, Escorial, Bar Ilan 170, Oxford: Heb. b. 10/29–36) all have Rabba bar Avuah. So too, when the Aruch (entry כַּלְבּוֹס) quotes the Gemara, it’s Rabba bar Avuah. Similarly, the Aruch and many manuscripts1 have Rav Pappa bar Shmuel, not Rava bar Shmuel.

Rava / Rav Pappa bar Shmuel

Rava / Rabba bar Shmuel is a third-generation Amora, a reciter of braytot in the days of Rav Chisda and Rav Sheshet. Sefer Yuchsin claims he’s the son of the famous Shmuel; Rav Hyman argues there’s no evidence of this.

Rabba bar Shmuel translates certain technical terms. Thus, in Bava Metzia 20b, Rabba bar bar Chana defines the Mishnah’s chafisa as a small flask; Rabba bar Shmuel defines the Mishnah’s deluskema as a container used by the elderly. In Berachot 35b, he defines anigeron as water in which beets were boiled and ansigeron as water in which other vegetables were boiled. Perhaps importantly, in Moed Katan 10a, after the Mishnah said that a craftsman making stitches on Chol Hamoed may only מַכְלִיב, Rabbi Yochanan defines it as skipping the middle stitch, while Rabba bar bar Shmuel says שִׁינֵּי כַלְבְּתָא, like the teeth of a dog, meaning not in a straight line. There, I don’t see any manuscripts with Rav Pappa bar Shmuel. But it is a definition of a כלב word describing a craftsman performing poor work.

Rav Pappa bar Shmuel was a third and fourth-generation Amora, who was a student of Rav Chisda and Rav Sheshet. Rav Hyman writes that, probably, when fourth-generation Pumbeditan Amoraim Abaye and Rava were before Rabba and Rav Yosef, Rav Pappa bar Shmuel was a Pumbeditan judge. Thus, in Sanhedrin 17b, דייני דפומבדיתא refers to רב פפא בר שמואל.

The Mamas and the Pappas

In my recent Link article, (“Confusing Rava and Rav Pappa,” January 4, 2024), I discussed a case where the Gemara suggested Rav Pappa said a particular statement, not Rava. Tosafot established the Amora in question as Rava, not Rabba, because that’s a possible transmission error—Rav Pappa said something, and those who heard mistakenly assumed he was quoting his primary teacher, Rabba. I mentioned how Rabbi Dr. Yaakov Elman wrote of errors of recollection in oral transmission, where a related Amora is mentioned. I personally championed errors in written transmission, since רב פפא minus פפ is רבא, and since many changes from רבא to רב פפא occur immediately before a פ word. There are many, but I gave an example from Bava Kamma 11b, אָמַר רַב פָּפָּא: פְּעָמִים.

In this sugya, we have a Rava / Rav Pappa variation, not involving the famous teacher-student pair. Perhaps whatever process causes the confusion globally (error of association, orthographic error) caused it here.

Another possibility: the names are semantically similar. Rabba / Rava is a contraction of Rav Abba, where Abba means “father.” Meanwhile, I’d guess that Pappa / Pappa, and occasionally Pappas, is from the Ancient Greek πάππας (pappas), meaning “daddy,” as opposed to the more formal πατήρ / patēr / father. (Pappos, πᾰ́ππος, means “grandfather.”) El Papa / the Pope similarly derives from this word for “father.” Rav Pappa is perhaps using a secular equivalent of Abba, akin to Tzvi / Hersh, Dov / Bear, Ze’ev / Wolf or even Yehoshua / Joshua. That probably doesn’t mean that Rav Pappa bar Shmuel and Rav Abba bar Shmuel are the same third-generation Amora, but it can explain the mental confusion.

Kalbus

The Aruch has three separate entries for כַּלְבּוֹס as used by Chazal. While initially this may seem implausible, recall that these are words borrowed from other languages, where they may have been spelled differently. The first, e.g. in Sotah 19b, refers to an iron hook / clamp / tongs, used to keep the mouth open. Rav Steinsaltz thinks that is the primary meaning of the word in our sugya, Greek κλάβος / Latin clavus / Hebrew צבת (clamp). But, he says, the Geonim explain it not a single dyeing, but split paths like a צבת. This is how the Aruch defines it, based on Rav Pappa bar Shmuel’s clarifying definition, though not tying it to the צבת. (Probably unrelated is Aruch’s second entry, Menachot 63a, a Temple vessel, a deep pan with three legs, from Greek כיליבס.) Finally, Rav Steinsaltz mentioned that some try to explain it as χιλι + βας, “1000 having,” meaning that it has a thousand colors in one garment.

Finally, the Aruch is compelled to explain our sugya’s כַּלְבּוֹס differently from the standard because after Rabba bar Avuah said כָּאוּר was כַּלְבּוֹס, the Gemara asked מַאי כַּלְבּוֹס and Rav Pappa bar Abba responded with a different definition. However, some manuscripts simply have מאי היא (though referring to כַּלְבּוֹס), and Bar Ilan 170 omits simply juxtaposes the two definitions, with nary a מאי. This is akin to Moed Katan, where Rabbi Yochanan and Rabba bar Shmuel argued in defining מכליב.

If these Amoraim argue, maybe the dyer does a poor job by using iron tongs to move the fabric in the cauldron. You shouldn’t trust ChatGPT, but I asked it nicely and it produced a lengthy and persuasive exposition of how use of tongs could potentially lead to poor results: uneven dye distribution (as the fabric bunches up); physical damage to the fabric (due to physical pressure, especially on gentle fabrics); direct contact marks (where the tongs touch the fabric, leaving it undyed or with less color intensity, as compressed fabric cannot absorb as well); difficulty in maintaining consistent temperature and exposure (since it’s harder to move the fabric gently and consistently in the bath); and chemical reaction with the dye (for metal tongs, reacting to the dye or mordants, especially if the dye bath is acidic or alkaline).

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.

1 Printings / Hamburg 165 have Rabba bar Shmuel. Vatican 116 has Rav Pappa amar Shmuel.