At a siyum at the end of a Talmudic masechet, a common practice is to recite the 10 “sons of Pappa.” They are חנינא בר פפא, רמי בר פפא, נחמן בר פפא, אחאי בר פפא, אבא מרי בר פפא, רפרם בר פפא רכיש בר פפא, סורחב בר פפא, אדא בר פפא, דרו בר פפא. A common, though mistaken, explanation is that these are all brothers, the sons of the famous Rav Pappa, student of Rava, and that when he made a siyum, he would invite them. Rav Hai Gaon explains how this isn’t true. Several were of earlier different scholastic generations, so weren’t the sons of fifth-generation Rav Pappa.

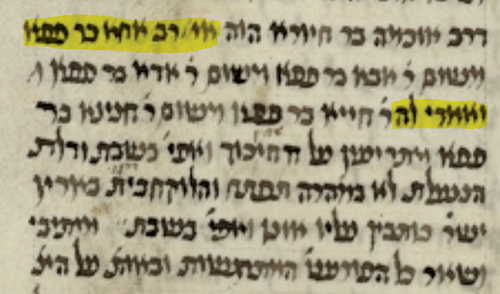

This becomes relevant in our sugya (passage), on Bava Kamma 80b. There are three statements: (a) The court sounds the alarm on Shabbat over a breakout of sores; (b) a door that is locked will not be opened quickly; and (c) with regard to one who purchases a house in Eretz Yisrael, one writes a bill of sale for this transaction even on Shabbat1. The attribution, or citation chain, of these three statements aren’t clear. Our Gemara has three versions. Labeling Amoraim, we have (A) Rav Acha bar Pappa, (B) Rav Abba bar Pappa, (C) Rav Adda bar Pappa, (D) Rabbi Chiyya bar Pappa, and (E) Rabbi Chanina bar Pappa. The Gemara has A cites B cites C; or alternatively B cites D cites A; or alternatively B cites A cites E. Some manuscripts have different versions, so Vatican 116 merges the middle and final alternative into D citing E, and Escorial has the first as A cites B and the last as B cites Rabbi Chanina (not bar Pappa).

The Bar Pappa Biographies

What do we know about these five? It is likely difficult to get a clear picture, because אדא, אחא, and אבא are orthographically similar, but we can try. We’ll consult Toledot Tannaim vaAmoraim, by Rav Aharon Hyman.

(A) Third-generation Rav Acha bar Pappa, also known as Rav Acha Aricha (the Tall), seems to have been a Babylonian. In Menachot 35b, he quotes second-generation Rav Huna about when to recite the blessing on tefillin. In Berachot 33a, Rav Acha Aricha recites a brayta before Rav Chinana, which manuscripts all have as “before Rav Huna.” Afterwards, he ascended to Israel and learned from all of Rabbi Yochanan’s great students. Thus, for example, Shabbat 111a, “Rav Acha Aricha, who is Rav Acha bar Pappa, raised a contradiction before Rabbi Abahu.” It may be that he’s a bar Pappi, not bar Pappa. Thus, Oxford 366 to Shabbat had “bar Pappi.” So does Yerushalmi Yevamot 8:2, where Rav Acha bar Pappi asks before Rabbi Zeira.

(B) Third-generation Rav Abba bar Pappa was also Babylonian. In Bava Metzia 43b, his colleague, Rabbi Zeira, asks that when he travels to Israel, he should take a circuitous route to visit second and third-generation Rabbi Yaakov bar Idi, to inquire whether he’d heard a specific halacha from Rabbi Yochanan. In Eruvin 63b, he explains that Yehoshua was childless as punishment for preventing the Israelites from peru u’revu (procreation) for one night.

(C) The only reference we seem to have (in Vilna) to R’ Adda bar Pappa is our own sugya. Further, the Escorial manuscript omitted C in the citation chain, and regardless, in the sugya, it is probably three separate versions because scribes couldn’t keep their bar Pappas straight. Yet, there’s a mnemonic, חב״ד בי״ח בח״ן to keep these three versions straight, but this was after the fact, and occurs in printings and the Florence 7 manuscript, but not in other manuscripts. Adda is an easy corruption of Acha or Abba.

Even if he didn’t exist, he’s mentioned in the Hadran. To keep a count of 10, perhaps we can substitute Rav Shmuel bar Pappa who interpreted before Rav Adda in Yoma 37a, except that’s also a corruption, and manuscripts have Rav Shmuel bar Acha who interpreted before Rav Pappa.

(D) Rabbi Chiyya bar Pappa appears in Sanhedrin 34b, where he cites the verse “And let them judge the people at all time” to justify the Mishnah’s statement that judgment can occur by day or night. That’s in printings, but manuscripts all have Rav Acha bar Pappa. In Yerushalmi Berachot 6:1, after fourth-generation Rabbi Yaakov bar Zavdi quotes Rabbi Abahu that one recites the blessing of HaEtz on olive oil, Rabbi Chiyya bar Pappa says before third-generation Rabbi Zeira that a Mishnah implies this. However, the Rome Yerushalmi manuscript has Rabbi Chinena bar Pappa, so maybe he also doesn’t exist.

(E) Third-generation Rabbi Chanina bar Papa (or bar Pappi) occurs quite frequently, especially in aggadic contexts. He received traditions from second-generation Rabbi Yochanan, first and second-generation Zeiri, and in aggada from third-generation Rabbi Shmuel bar Nachmani. In Yerushalmi Sheviit 4:3, he and Rabbi Shmuel bar Nachmani pass people plowing during Shemitta, and the latter tells them אַיַּשֵּׁר (meaning “shkoyach”). Rabbi Chanina bar Pappa says, “didn’t Rebbe interpret Tehillim 129:8, “the passersby shall not say [the blessing of Hashem upon you]” that it’s forbidden to say “shkoyach” to one plowing during shemitah? The latter told him, “you know how to read, but not to make a homily”, then explained how to alternatively interpret the verse.

Selecting a Version

If it were up to me to select a girsa (expression) from the three alternatives in our Vilna Shas for our sugya, I’d dismiss any variant involving the seemingly non-existent C and D. That would leave us with the final variant, אָמַר רַבִּי אַבָּא בַּר פָּפָּא מִשּׁוּם רַבִּי אַחָא בַּר פָּפָּא מִשּׁוּם רַבִּי חֲנִינָא בַּר פָּפָּא.

Further, these are three bar Pappas, all of the same, third scholastic generation. It’s strange for them to cite each other. Was it really originally just one bar Pappa saying this? Alternatively, there are also three statements. What if each bar Pappa said a separate statement, a-A, b-B, and c-C, and they were grouped and preserved as a bar Pappa corpus, with אָמַר turning into מִשּׁוּם? Indeed, consider that Rabbi Chanina bar Pappa says (c), about purchasing a home in Israel, and it’s followed by Rabbi Shmuel bar Nachmani also discussing purchasing a city in Israel.

1 This last statement is also said by third-generation Rav Sheshet on Gittin 8b.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.