The morning of my wedding, my ears suddenly clogged. All sounds were muffled. I got an appointment with an ENT, who was surprised at how much waxy buildup had developed in my ears. They used a hydrogen peroxide solution and cleared out all the wax. But they were highly amused by how much wax this Wax-man had accumulated. A few weeks back, in Nedarim daf Peh Zayin (87), we encountered a statement by רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן בֶּן פַּזִּי. Had I not known that the pagination was set by Daniel Bomberg, a Christian, in 1523, I might have thought that this was deliberate. Just as Bava Kamma 46a deals with an ox that gored a cow, and as Yoma 86b begins Rava’s statement mentioning dung. This is just the mind making connections, sometimes spurious.

I discussed this phenomenon earlier in an article, “It’s the Eponymy, Stupid” (August 25, 2022). Sometimes, a Tanna or Amora will say something that matches up with his name, and some scholars (notably Rabbi Louis Jacob) took this as evidence, alongside other proofs, that many Talmudic attributions of statements are pseudepigraphic. I’m unpersuaded, for several reasons I explain in my article.

So last week, we encountered Rav Matna or Rav Mattana I, a second-generation Babylonian student of Shmuel. Two of his listed derashot involve gematria (יִהְיֶה as thirty days of standard nazirut, and Moshe equal to and בְּשַׁגַּם). He uses wordplay to discover Pentateuchal allusions to Haman, Esther and Mordechai. Should we be truly surprised when, in Eruvin 54b, he directs his focus to interpret וּמִמִּדְבָּר מַתָּנָה about making oneself humble like the wilderness to acquire Torah?

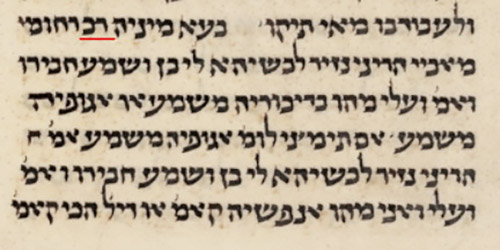

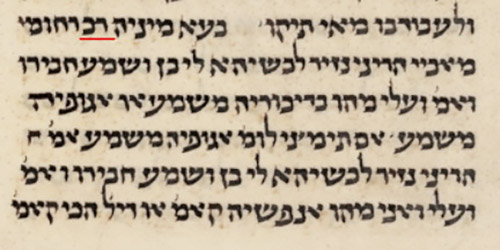

This brings us to Ben Rechumi. Rabbi Jacobs writes in a footnote, “In the case of Ben Rehumi and Ayo, for instance, it is as clear as can be that the names have been invented by the editors.” It appears he believes that the very names themselves are inventions, since they are strange and perfectly match to the sugya. The Mishna had discussed the law when a man says הֲרֵינִי נָזִיר לִכְשֶׁיִּהְיֶה לִי בֵּן, accepting nazirut when he has a son. Ben Rechumi asked, if Reuven makes the Mishna’s declaration for his own son, and his friend Shimon hears and says וְעָלַי, and upon me, shall we interpret it as contingent upon the birth of Reuven’s son, or upon Shimon’s son? Does it (A) devolve on the statement and the statement’s target, or (B) upon himself with analogous relationships? There are two follow-up questions. Assuming (B), would וַאֲנִי have the same implications of וְעָלַי? Does Shimon again mean himself (B), or does וַאֲנִי mean (C) “I love you as you love yourself”, רָחֵימְנָא לָךְ כְּווֹתָיךְ? And what if Reuven declares this about Levi’s son being born, and Shimon says וַאֲנִי? Since it’s not before Levi, does (B) hold, or does he mean that he loves Levi like Reuven loves Levi? “Love” in this case is רָחֵימְנָא, like Rechumi, and it is about a ben, a son.

We might attribute these follow up questions to Ben Rechumi or to the Talmudic Narrator. Even if to Ben Rechumi, are we really interpreting וַאֲנִי as “I love you equally” or essentially as an expression of camaraderie, saying that he directs towards the original target? Is this love intrinsic to (two of his follow-up) questions, or is it a clever play on words once he’s already asking?

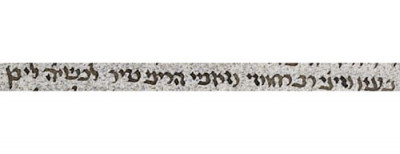

Regardless, while Vilna and Venice printings have Ben Rechumi, never encountered elsewhere, both Munich 95 and Vatican 110 have Rav Rechumi. “Ben” and the connection to the born child is thus discarded. As for Rav Rechumi, several Talmudic Sages bear this name, which is the Aramaic translation of Hebrew “Ahava,” another known Talmudic name.

Fourth- or fifth-generation Rav Rechumi I was either the colleague or the student of Abaye (Nazir 13a, Pesachim 39a) and Rava who died within Rava’s lifetime (Ketubot 62b), thus associated with Pumpedita and Mechoza. Sixth- and seventh-generation Rav Rechumi II was the student of Ravina I (Zevachim 77a, Chullin 89a, Yoma 78a), heading Pumpedita academy after Rafram. Rav Rechumi/Nechumi III was a Savora yet mentioned in Menachot 33a; Eruvin 11a, 71b. There’s mention of Rav Rechumi from Birta Shechora (Or Zarua to Megillah 21a) and Rabbi Rechumi (in Zohar). Given his inquiry to Abaye, we are dealing with Rav Rechumi I.

Indeed, the nature of his primary inquiry, about עלי and אני, and whether אַדִּיבּוּרֵיהּ מַשְׁמַע, אוֹ אַגּוּפֵיהּ מַשְׁמַע, matches well with the אִיבַּעְיָא לְהוּ, the inquiry before the Sages earlier on Nazir 11b, which eventually (Pumpeditan/Mechozan) Rava and his student Rav Huna berei deRav Yehoshua about אני without עלי and whether אַכּוּלֵּיהּ דִּיבּוּרָא מַשְׁמַע, אוֹ דִלְמָא אַפַּלְגֵיהּ דְּדִיבּוּרָא מַשְׁמַע. This dispute, and the people, aren’t fabricated—these are questions arising in approximately the same beit midrash.

In Pesachim 39a, after the Mishna listed five vegetable species one could use for maror and Amoraim explained that various other vegetables satisfying certain criteria were also valid, Rav Rechumi I asked Abaye that if it’s a mere matter of bitterness (perhaps because of מְרוֹרִים), why not use the bile of a kufya fish. Abaye responds by drawing a connection between matzah and maror, both from the plant kingdom. Next, Rabba bar Rav Chanin, Abaye’s colleague, challenges him about multiple maror options, to which Abaye cites the plural מְרוֹרִים. Regardless, we thus see the Abaye/Rav Rechumi connection repeated, and a concern about the import of language.

Ketubot 62b relates that Rav Rechumi, who frequently “was before” Rava in Mechoza (thus implying as a student) would come back to his home every Yom Kippur. Once, engrossed in the study of a halacha, he didn’t return home, even as his wife waited expectantly. She shed a tear, and the roof he was sitting on collapsed, killing him. In its context of discussion of onah for talmidei chachamim, the lesson here is to balance Torah study and familial obligation, as well as how one’s even exemplary actions can emotionally impact others.

While the above interactions mostly indicate a student relationship, perhaps he was a colleague. In Eruvin 14b, third-generation Rav Yosef cites second-generation Rav Yehuda who cites first-generation Shmuel, that the halacha doesn’t follow Rabbi Yossi regarding brine or sideposts. Meanwhile, Rav Rechumi had a different version, מַתְנֵי הָכִי. He says that second-generation Rav Yehuda bar (first-generation) Rav Shmuel bar Sheilat said in the name of Rav that the halacha doesn’t follow Rabbi Yossi regarding brine or sideposts. The difference is only in attribution. And, not just Rav vs. Shmuel as the final target, but in Rav Rechumi’s chain, there is mention of a different Rav Yehuda and a different Shmuel. The Gemara continues that someone later asked Rav Rechumi if he indeed said this, and he denied it. To this, Rava exclaimed, “Gosh! He said it, and I learned it from him!” The Gemara (presumably, rather than Rava) explains Rav Rechumi’s retraction based on the halacha typically following Rabbi Yossi, because his reasoning is with him.

As discussed elsewhere, Rava only learned from Rav Yosef later in life. And, while he might learn from a student, he might also learn from a colleague. Might we draw a psychological connection between Rav Rechumi’s changing his tune and not admitting his prior tradition with the question in our sugya of whether a person saying וַאֲנִי might be embarrassed to intend anyone other than the original speaker? Regardless, Rav Rechumi is a real holy and flawed individual, who interacts with Abaye and Rava, and wasn’t invented for fun wordplay.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.