Regarding marriage, my father once suggested a novel interpretation of the opening mishna of Bava Metzia (2a). שְׁנַיִם אוֹחֲזִין בְּטַלִּית—“Two people are ‘holding’ by the tallis,” standing under the chuppah. זֶה אוֹמֵר אֲנִי מְצָאתִיהָ—“He says: ‘I’m the metziah, the real find,” וְזֶה אוֹמֵר אֲנִי מְצָאתִיהָ—“And she says, ‘I’m the metziah.’” זֶה אוֹמֵר כֻּלָּהּ שֶׁלִּי—“He says, ‘It’s all about me,’” וְזֶה אוֹמֵר כֻּלָּהּ שֶׁלִּי—“And she says, ‘It’s all about me.’” Such a shidduch cannot sustain, so what happens? זֶה יִשָּׁבַע—“He starts to swear, ‘@#$%&!,’” וְזֶה יִשָּׁבַע—“She starts to swear,” וְיַחְלוֹקוּ— “And they split up … ”

The opening Gemara of the masechet is mostly Aramaic and anonymous, thus perhaps Savoraic. It analyzes the mishna’s language. Why did the mishna’s author not only teach אֲנִי מְצָאתִיה, and I’d understand the claim was, “It’s all mine?” The Gemara answers that otherwise, we’d think that he’d acquire it through mere sight. The extra language teaches this additional point, that he not only saw it—but also acted to acquire it—and this is his claim.

How could one get this false impression from אֲנִי מְצָאתִיה After all, Ravnai (רבנאי) said in a different context1 that וּמְצָאתָ֑ה implies it physically came to his hand. The Gemara answers that we might have distinguished between biblical and colloquial language.

Different Context

Rashi (ad loc.) points us to that different context, namely Bava Kamma 113b. This feels like a different tractate, but as discussed in Bava Kamma 102a, we might consider all of Nezikin to be a single tractate. Thus, Bava Kamma, Metzia and Batra as the first, middle and last gates to Nezikin. The Talmudic narrator is free to make connections throughout the Talmud, but this is actually something fairly close in scope.

How does Ravnai’s statement operate there? Well, Devarim 22 describes someone encountering a lost item, and how he’s obligated to return it, which might involve a lot of care and effort. In certain cases, the obligation doesn’t apply, and he can either keep it (if it’s in his possession) or alternatively ignore it and walk on. Perhaps that’s only if he hasn’t picked it up and assumed some responsibility? Ravina says that וּמְצָאתָה has the implication that it has come into his hand. Thus, the point isn’t about how one acquires a lost item, but that the derasha about not needing to return operates (even) on a biblical case where it’s already under his control.

In context, we might wonder whether דַּאֲתַי לִידֵיה—“that it came into his hand,” must literally mean that it “entered into his hand,” or rather, conceptually, that it’s somehow in his possession/domain? Among the sugyot to explore: See Shabbat 153a, about a lost item entering the finder’s possession before Shabbat; Bava Metzia 21b, about an item entering his possession before the loser’s abandonment, thus while still forbidden; Bava Kamma 5a, about whether funds entered his possession legally or illegally; and especially Bava Batra 126a, about a firstborn relinquishing his extra share only regarding fields he already possessed. The general feel is conceptual. Indeed, fields don’t literally “come into his hand.”

In Bava Kamma 93a, Rav Huna discusses a mishna where Reuven tells Shimon to destroy his jug or tear his garment—where Shimon is liable—contrasted with a baraita about liability if one gives to a watchman to watch, לִשְׁמוֹר—as the Torah puts it—versus to destroy or tear. Rav Huna explains that the mishna was דַּאֲתַי לִידֵיהּ, it entered his possession (as a watchman first). Rabba objects: לִשְׁמוֹר indicates דַּאֲתַי לִידֵיהּ; rather, the distinction is whether it entered for safeguarding or for tearing. This might be literally “entering his hand,” but really seems like conceptual control over it.

Furthermore, does Rabba there really intend the same as what we’re attributing to Ravnai, that biblical לִשְׁמוֹר means it must physically “enter his hand?” What about the word indicates this? Similarly, וּמְצָאתָהּ for Ravnai logically means that he’s already a finder of that item, and he’d normally already be obligated to return it in other scenarios, so the question is whether he need bother—not some point about the legal means of obtaining the item, via “seeing” versus “grabbing.” If mere sight with intention acquire would theoretically work, perhaps Ravnai would consider that וּמְצָאתָה.

Tosafot points to Bava Metzia 118a as a possible counterexample, where הבטה—“viewing,” as distinct from physically lifting, acquires barley from hefker. They answer that that viewing also involves some minor act, like building a small fence around the barley. (Even so, this isn’t literally “entering their hand.” What we seem to be saying is mere sight versus some physical act to acquire.)

Tangentially, on Bava Metzia 27b, Ravnai’s analysis of the implications of וּמְצָאתָהּ becomes an explicit attributed derasha for the Sages in a derasha chain; Rabbi Yehuda who argues interprets the word as exempting returning an item worth less than a perutah.

Acquiring Via Sight

Meanwhile, the mishna 1:4 on Bava Metzia 10b discusses “one who saw a lost article,”—רָאָה אֶת הַמְּצִיאָה—“and fell upon it, and another person grabbed it”—the grabber acquires it. In the Gemara, Reish Lakish cites Abba Kohen Bardela/bar Delaya, that one’s four cubits acquire for him. (In the parallel Yerushalmi, Rabbi Yochanan disagrees.) There are objections from various Tannaitic sources, including this mishna. The answer is that his falling upon it showed he intended to acquire specifically in this invalid way.

The same mishna discusses one who sees (רָאָה) people chasing a crippled gazelle (צְבִי) and says “My field should acquire,” it works. I’d ask: Do these two cases demonstrate that sight alone acquires, with no action? No, we can say that he sees it, but it’s his four cubits—or his courtyard/field—that acquire. As evidence, consider that he saw it eight cubits away, or outside his property, he wouldn’t acquire it.

Ravina or Ravnai?

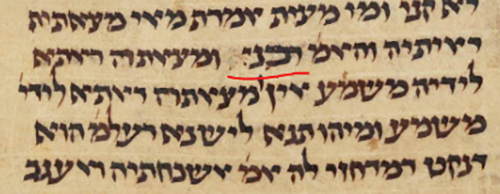

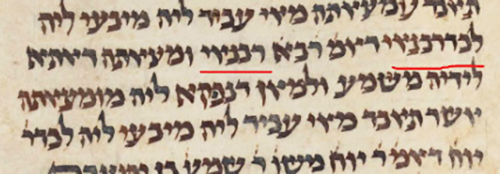

The primary sugya for וּמְצָאתָה is Bava Kamma 113b, where all printings and most manuscripts on Hachi Garsinan have Ravina, (Munich 95 has רבנא). To consider the secondary sugyot, our daf—Bava Metzia 2a, Vilna and Venice printings have Ravnai, Hamburg 165, Munich 95, Escorial and Vatican 115 and 117 have Ravina. Still, Florence 8-9 has something unclear, but it seems like the “bet” and perhaps a “yud” were crossed out (from Ravina) and overwritten with a “bet,” and the final “aleph” was mostly erased to for a “yud” (Rabbanei, “the Sages”).

I initially thought that this was a transposition error, moving the “yud” of רבינא to the end, רבנאי, and that the prevalence in printings was, perhaps, due to Gutenberg’s printing press and its moveable type. After all, different means of transmission (oral, handwritten, printing press, typed or word-processed) make different kinds of errors more likely. However, the other secondary sugya—Bava Metzia 27—only has Ravina in Hamburg 165. The printings, Florence 8-9, Munich 95, Escorial and Vatican 117 all have Ravnai; Vatican 115 has Ravana (with a slight error, dotted over, of Rava). Thus, this transposition error predated printing. Despite not being the primary sugya, I’d favor reading the more difficult, rarer Ravnai over the more common Ravina.

What do we know of Ravnai? Could it be רַבָּנַאי and the plural for many Sages? A Sefaria search for “Ravnai” has him citing Shmuel in Yoma 21a, Bava Batra 99a, Chullin 76b and Keritot 13a. There may be more or less, due to transposition errors with Ravina. Regardless, he seems to be Shmuel’s student2. There’s also Ravnai, brother of (third-generation) Rabbi Chiyya bar Abba. Hyman writes that these brothers originated in Bavel and learned from Shmuel in their youth, but Rabbi Chiyya bar Abba later ascended to the land of Israel. “Ravnai,” Hyman writes (pointing to Ketubot 50b), “is a contraction of Rav Benai.” Rav Yechiel Heilprin says that it’s a contraction of Rabbi Yannai. Scholars debate whether Ravnai alone is the same as Rabbi Chiyya bar Abba’s brother, or (Albeck) he’s a separate person. Regardless, it’s fair to assume that our Ravnai of Bava Metzia is real, and Shmuel’s student.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.

1 Since it’s the Talmudic narrator quoting it from elsewhere, this does break the Stammaic nature of the beginning of the tractate. Later on the page, we have fifth-generation Rav Pappa, his contemporary Rav Shimi bar Ashi or “Kedi.” As I’ve discussed in a prior article (“Hello Kedi,” June 2, 2022), “Kedi” isn’t a scholar’s name, but means “unattributed.” In other words, this continues the Stammaic nature. Perhaps Rabbi Chiyya on 3a, then Rav Pappa on 3a and Rav Sheshet on 4a, would be the pre-Stammaic sugya.

2 Rav Hyman—in Toledot Tannaim vaAmoraim—separates another potential Amora by mentioning Brachot 38a, where he cites Abaye with the caveat that “dikdukei soferim” says this should be Rava. I think it is strange for Rava to cite Abaye. Ravina I, with a transposition error, seems more likely.