Rabbi Dr. Daniel Sperber, in Minhagei Yisrael, discusses a minhag of the Jews of Rome: instead of the first-born males fasting on Erev Pesach, and hearing a siyum so that they don’t have to fast, this is done instead by the women who’ve gotten married over the past year… They call it the Roman kallah-siyum1.

That’s the way I like to end a masechta, with a good joke. Chazal likewise often ended a masechta on a good note, with אָמַר רַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר אָמַר רַבִּי חֲנִינָא: תַּלְמִידֵי חֲכָמִים מַרְבִּים שָׁלוֹם בָּעוֹלָם, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: וְכׇל בָּנַיִךְ לִמּוּדֵי ה׳ וְרַב שְׁלוֹם בָּנָיִךְ. Aside from ending Nazir, it also concludes Yerushalmi Berachot, and Bavli Berachot, Yevamot, Keritot and Tamid. Rabbi Shaul Leiberman was asked for an example of Talmudic humor, and he came up with תַּלְמִידֵי חֲכָמִים מַרְבִּים שָׁלוֹם בָּעוֹלָם.

These parallel sugyot sometimes vary. Tamid 32b in Vilna and Venice printings has third-generation Tanna, Rabbi Eleazar ben Azariah, and omits Rabbi Chanina, but this doesn’t occur in our manuscripts.

Who Said It?

The same Rabbi Eleazar citing Rabbi Chanina famously said (Megillah 15a) כׇּל הָאוֹמֵר דָּבָר בְּשֵׁם אוֹמְרוֹ מֵבִיא גְּאוּלָּה לָעוֹלָם, so we should take pains to identify who these people are. Unadorned Rabbi Eleazar is either the Tanna, Rabbi Eleazar ben Shamua, or the second-generation Amora, Rabbi Eleazar ben Pedat. Meanwhile, plain Rabbi Chanina could be either a fourth-generation Tanna or one of three Amoraim.

We find this citation pattern (רַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר אָמַר רַבִּי חֲנִינָא) many times through Shas . Berachot 27b has אָמַר רַבִּי זֵירָא אָמַר רַבִּי אַסִּי אָמַר רַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר אָמַר רַבִּי חֲנִינָא אָמַר רַב: בְּצַד עַמּוּד זֶה הִתְפַּלֵּל רַבִּי יִשְׁמָעֵאל בְּרַבִּי יוֹסֵי שֶׁל שַׁבָּת בְּעֶרֶב שַׁבָּת. First-generation Amora Rav appears at the end, discussing the practice of sixth-generation Tanna, Rabbi Yishmael beRabbi Yossi. Therefore, it is the Amora Rabbi Eleazar ben Pedat citing Rabbi Chanina HaGadol (bar Chama). Rabbi Eleazar served Rav in his youth, traveled to Israel and studied from Rabbi Chanina before turning to Rabbi Yochanan.

Spurious Derasha?

Rabbi Dr. Robert Gordis, in an article in Jewish Quarterly Review3 about the meaning of the al tikrei, writes, “It may be argued that the entire ’al tiqrē is superfluous. Since the first stich of the biblical verse declares that “all your children will be taught by God,” and the second stich that “great will be the peace of your children,” one could logically infer that since things equal to the same thing are equal to one another, all those taught of the Lord would have great peace. There would thus be no need for recourse to the ’al tiqrē and the intrusion of the irrelevant “your builders.” Since Rabbi Hanina does introduce the ’al tiqrē in the second stich, it is clear that he has not adopted the path of the Euclidean axiom for arriving at his conclusion. In fact, it is clear that he bases himself entirely on the second stich for his derash. He is proposing that בניך be understood, not as “your sons,” but as the “Qal participle of…” I’ll end the quote here.

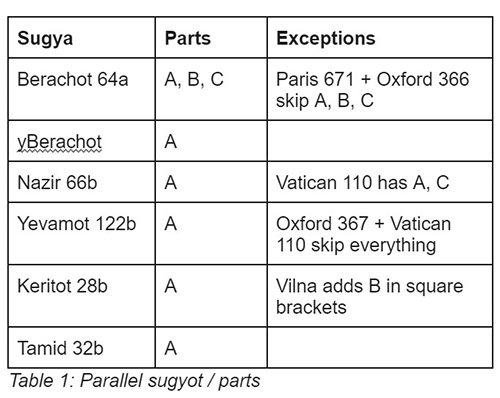

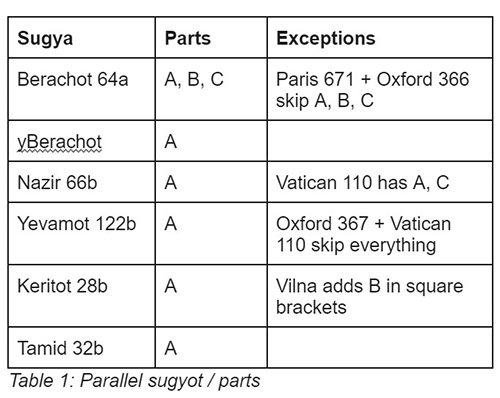

The most complete sugya contains: (A) Rabbi Eleazar cites Rabbi Chanina that Torah scholars increase peace in the world, based on the verse in Yeshaya 54:13. (B) The famous al tikrei, don’t read banayich but bonayich; (C) Three other biblical verses, each dealing with peace. Table 1 summarizes what we find in each masechet, as collected in Hachi Garsinan, which includes both printed texts and manuscripts.

Could Gordis’ hava amina be correct? Is the al tikrei original to the sugya? Consider that across most sugyot and manuscripts, (B) doesn’t appear. Only the expansive/flowery Bavli Berachot 64b has it, but with some manuscript exceptions, and the Yerushalmi parallel omits it. Consult Table 1. What if it’s a scribal insertion?

If so, contra Gordis, the derivation could not be mere Euclidean axiom. We don’t need one Amora citing another to tell us a pasuk. Rabbi Yochanan said, “Thou shalt not kill!” Rather, limudei Hashem means “disciples of the Lord,” suggesting they practically follow in Hashem’s ways, but this is shifted to refer to those who study Torah.

But does it truly make sense to say the al tikrei was added? On the one hand, lectio brevior potior, the shorter reading is strongest. On the other hand, we need to think through the process by which a text would be modified from the original, and which direction would be harder to traverse. That is the motivator behind lectio difficilior potior, the seemingly more difficult reading is stronger. Would a scribe really add an entire means of derivation?

Innovating al Tikrei

As I’ve learned through midrashim, in Shas and elsewhere, I’ve spotted dozens of what seem to be an underlying, yet hidden, derasha, unstated by the text itself or the classic commentators. For instance, in Succah 2a, Rabba deduces a 20 cubit height limit for a sukkah based on ״לְמַעַן יֵדְעוּ דוֹרוֹתֵיכֶם כִּי בַסּוּכּוֹת הוֹשַׁבְתִּי אֶת בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל״, עַד עֶשְׂרִים אַמָּה, אָדָם יוֹדֵעַ שֶׁהוּא דָּר בַּסּוּכָּה, לְמַעְלָה מֵעֶשְׂרִים אַמָּה — אֵין אָדָם יוֹדֵעַ שֶׁדָּר בַּסּוּכָּה, מִשּׁוּם דְּלָא שָׁלְטָא בַּהּ עֵינָא. I’d posit that the derasha is אַל תִּקְרֵי דּוֹרוֹתֵיכֶם אֶלָּא דִּירוֹתֵיכֶם, with the follow-up up whether a person is “yodea” (knows) that he is “dar” (lives) in the sukkah. And of course, the idea that the schach shouldn’t form a thick, solid roof is literal al tikra.:)

Similarly, Savoraim may propose an al tikrei. Or, commentary by a Rishon in the margins might be copied into the Talmudic text by an errant scribe. Consider Berachot 31b: וְאָמַר רַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר: חַנָּה הֵטִיחָה דְּבָרִים כְּלַפֵּי מַעְלָה. שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר ״וְתִתְפַּלֵּל עַל ה׳״, מְלַמֵּד שֶׁהֵטִיחָה דְּבָרִים כְּלַפֵּי מַעְלָה. Rashi rejects a girsa that reads אַל תִּקְרֵי אֶל אֶלָּא עַל ה׳, since that’s how the verse is indeed spelled. Rashi proposes an al tikrei for one explanation in Shabbat 12b, and rejects an al tikrei in Sotah 35b, אַל תִּקְרֵי מִמֶּנּוּ אֶלָּא מִמֶּנּוּ, where the words are spelled and pronounced identically. Inserting/removing this derasha isn’t surprising.

Not Sons, Rabbits/Braiders

My father has frequently repeated the following explanation that he heard in the name of Rabbi Dr. Michael Bernstein zt”l. We typically translate this: read not sons but builders. This seems odd. In what way are Torah scholars builders? (And we can answer how, but it seems forced, or is an extra step.) The better explanation is “read not sons but understanders.” Think בינה; a scholar is one who understands.

In a recent email exchange, his son, Rabbi Dr. Moshe Bernstein, explained to me (with sources of Gordis and Yalon) the grammar behind the derasha. While playing with בנ roots, they either kept the kametz in בָּנַיִךְ but wrote the cholam as an artificial marker of the participle, or took it as a genuine participle of בָּנָיִךְ/understander. He also noted other instances where Chazal seem to say that Torah scholars are builders, but a close reading suggests that they were actually tapping “understanding.” For instance, in Shir HaShirim Rabba 1:5, אַל תִּקְרֵי בְּנוֹת יְרוּשָׁלָיִם, אֶלָּא בּוֹנוֹת יְרוּשָׁלָיִם, זוֹ סַנְהֶדְרֵי גְדוֹלָה שֶׁל יִשְׂרָאֵל שֶׁיּוֹשְׁבִין וּמְבִינִין אוֹתוֹ בְּכָל שְׁאֵלָה וּמִשְׁפָּט.

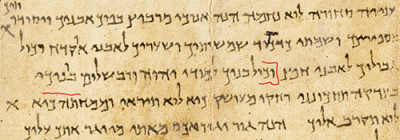

Also, he noted that the derasha is probably on the second occurrence of בָּנָיִךְ. The Qumran Great Isaiah Scroll has that instance spelled with a vav suspended in the word, which I’ve underlined in red (suggesting a scribe inserted it).

In the context of the perek, builders can actually work. Previous verses discuss building stones, gates, foundations and encircling walls. Together with the Qumran scroll, this lends credence to the al tikrei being real and original, perhaps based on a krei/ketiv alternation. If so, may I receive reward for demolishing my edifice just as I received reward for building it, just so long as we attain the proper understanding of the derasha. Shalom!

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.

1 No, he doesn’t really discuss such a minhag.

2 Berachot 27b, 64a; Megillah 5a, 15a (twice), Moed Katan 8b; Yevamot 122b; Nazir 66b; Sanhedrin 57a, 58b (twice), 111b; Keritot 28b; Tamid 32b (via manuscripts); and Zevachim 101b

3 Increasing Peace in the World: A Note on a Talmudic Passage, https://www.jstor.org/stable/i263459. Thanks to Dr. Moshe Bernstein, who provided lots of guidance, articles, references to the Qumran Isaiah scroll, mentioned here, and a lot not mentioned here. For brevity, I didn’t attribute everything. Though some are my own spin, so don’t attribute blame for those parts.