I was both fearful of and intrigued by “Maus” before I ever read it. Copies of the graphic novel were frequently seen in my middle school—left behind on a desk or lying on the floor by the lockers.

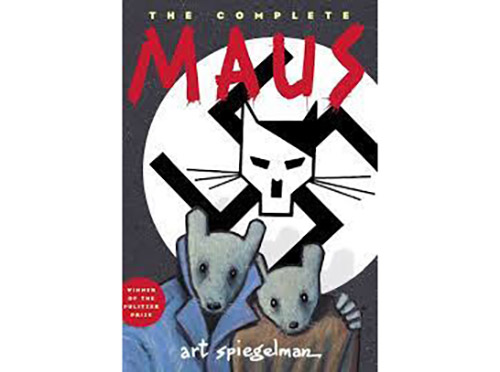

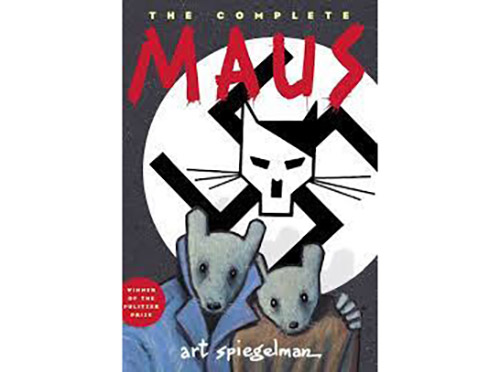

Unlike other books in the English curriculum, “Maus” was a graphic novel, a comic book. Also unlike other books, it has a huge swastika right on the cover. Both of these details made me simultaneously afraid and excited for eighth grade, when I knew I’d learn the story.

I found out recently that it was thanks to my particular eighth grade teacher that I read the book at all.

Diane Bohs, who taught English for 12 years at Joseph Kushner Hebrew Academy’s middle school and is currently the Rae Kushner Yeshiva High School English chairperson and coordinator, introduced the graphic novel to the curriculum. She felt it was an appropriate way to educate on the Holocaust, and that the unique format—where Jews are depicted as mice and Nazis as cats—made the book stand out. Students enjoyed the book.

“It gave me an opportunity to talk about the Holocaust, and it also gave the students an opportunity to teach me, because I’m a Christian,” Bohs said. “It was a very nice sharing, a back-and-forth.”

Bohs and I connected recently to discuss the book’s removal from the eighth grade curriculum in McMinn County, Tennessee. Both of us were appalled by the decision, as was much of the nation.

In a decision that has been largely criticized, the McMinn school board unanimously voted to remove “Maus” from the curriculum. The reasons given: “rough, objectionable language,” “profanity and nudity and its depiction of violence and suicide,” “too adult-oriented.” The story, which depicts author Art Spiegelman’s parents’ lifelong trauma resulting from the Holocaust, is known as much for its bleak content as for the animals it uses to tell the tale.

Bohs acknowledged the darkness of the story, particularly the scenes in which Spiegelman’s survivor mother commits suicide. She feels that it is necessary for teachers to provide context and consider the age of the audience, but that that shouldn’t preclude them from reading about the Holocaust altogether.

“You have to prepare your audience for what they’re reading,” she said. “You don’t just sweep it under the rug. You put it out there, you discuss it intelligently, you process it and you move on.”

The books that are part of Kushner’s curriculum were intentionally chosen for age level. I recall reading John Boyne’s “The Boy in the Striped Pajamas” and Uri Orlev’s “The Island on Bird Street” in sixth grade with Bohs. Both are tamer accounts of the Holocaust with child protagonists. By the time I was in high school, Bohs began introducing parts of Elie Weisel’s “Night,” a harsher nonfiction testimony with a teenage protagonist, to the eighth grade

McMinn county does plan to replace “Maus” with “other works that accomplish the same educational goals in a more age-appropriate fashion.” But until they announce their alternative, it is unknown what type of narrative will be used in its place.

Bohs feels that books should be taught with their context, not outright banned. In her high school classes, she discussed the “Maus: removal, and the concept of banning books in general, with her students. Most students feel that they should have the choice to determine what they read, particularly outside of the classroom.

“I talked about the fact that when I was in high school, if they said we couldn’t read a book, that was the first book I got from the bookstore,” she said. “I was curious!”

Bohs has taken parent concerns into account when it comes to age appropriateness. After she taught “The Catcher in the Rye” to ninth graders, parent complaints led her to place it in the 11th grade curriculum instead. Overall, however, the inappropriateness of language or characters was the point in teaching such stories in the first place.

“Always teach with an introduction to certain areas which students might find uncomfortable,” she said.

Eighth graders at Kushner, as it turns out, are no longer reading “Maus.” But the decision wasn’t due to the content of the story, just a change in curriculum. Other Holocaust narratives including “The Boy in the Striped Pajamas” and “Night” are still taught, not to mention other opportunities to learn, from history class to guest speakers to the eighth grade “Names Not Numbers” survivor testimony program. In a Jewish school like Kushner, knowledge of the Holocaust is never pushed aside. It is possible that a public school in a state that is 1% Jewish may eventually forget it.

Eighth graders in McMinn County, Tennessee, perhaps felt the same way I did 10 years ago, nervously excited to give the scary story a chance. Hopefully they now feel the same way Bohs did, ready to seek out “Maus” on their own, since that chance has been taken from them. But without the guidance of a teacher—one who leads the difficult conversations, as mine did—their understanding will be lacking.

Ariella Shua is a former Jewish Link intern who is currently working at Publicis Sapient as a junior associate product manager. She graduated from Johns Hopkins in 2021 with a degree in writing seminars, and minors in marketing and in museum studies. She lives in New York City