Taanit 9a describes two interactions between Rabbi Yochanan and Reish Lakish’s young son. In the first, Rabbi Yochanan asks the child to relate what verse he learned that day in school. Child: “A tithe shall you tithe.” Child (further*): And what does “a tithe you shall tithe” mean? Rabbi Yochanan: Tithe [aser], so that you become wealthy [titash’er]. Child: How do you know? Rabbi Yochanan: Go and test it. Child: And is it permitted to test Hashem? The child cites a verse in Devarim 6:16, where Moshe tells the Israelites not to test Hashem (as they did in Masah). Rabbi Yochanan: So says Rabbi Hoshaya, that one mustn’t test Hashem except in this. He cites a verse in Malachi 3:10, in which Hashem talks of tithes and material reward, and instructs them to put Him to the test on this. Child: Had I reached that verse, I wouldn’t have needed you or your teacher Hoshaya!

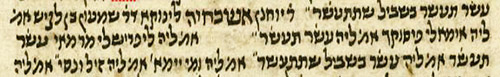

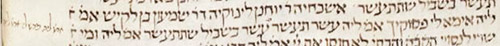

The Aramaic original is ambiguous in not labeling speaker or listener, repeatedly employing אֲמַר לֵיהּ, “he said to him.” In most such Talmudic exchanges it is easy to follow, as the speaker alternates. We begin with Rabbi Yochanan, the child goes next, then Rabbi Yochanan, and so on. The problem here is that the child speaks twice consecutively, responding with the verse and then asking as to its meaning. This repetition is unclear until the concluding remark, which is clearly the child speaking, at which point we reverse and figure out that the child spoke twice. As scribes contended with this awkwardness, they produced some interesting girsaot. Manuscripts prepend, e.g., לִפְרִישׁ לִי מַר, “let Master explain to me,” using a respectful term somewhat at odds with the boy’s later speech (see Herzog manuscript). Or, they omit the middle exchange and reintroduce in the margin (see Munich 140).

The child is quite young. He is called a ינוקא and displays mastery of verses of Torah and their implication, though he had not yet reached the verse in the middle of the very last chapter of the very the last of the books of Nevi’im, Malachi. Children typically began studying Mikra at five and began Mishnah at 10. (See Avot 5:21.) While highly intelligent, his manner of speech is impudent. Challenging Rabbi Yochanan with a demand for proof that the drasha is right, or objecting that one may not test Hashem, is boldness and just part of the battle of Torah. However, saying, “I wouldn’t need you or your teacher Hoshaya” is quite rude. He says that those rabbis aren’t needed and strips Rabbi Hoshaya of his rabbinic title. Also see Rosh Hashanah 31b, לָאו אוֹרַח אַרְעָא לְמֵימְרָא לֵיהּ לְרַבֵּיהּ ״רַבָּךְ״.

In a subsequent exchange, the child reads aloud the verse in Mishlei 19:3, that foolishness perverts a man’s way, causing him to fret against Hashem. Rabbi Yochanan wonders aloud where one can find a Pentateuchal allusion to this idea. They boy mentions the reaction of Yosef’s brothers when they discovered the money that had been planted in their saddlebags: “What is this that Hashem has done to us.” Rabbi Yochanan is impressed, but the boy’s mother takes him away, telling him “come away from him, lest he do to you as he did to your father.”

Rabbi Shimon b. Lakish lived in Tzipori from 200-275 CE, while Rabbi Yochanan (b. Nafcha) lived from 180-279 CE, so these incidents occurred in Tzipori from 276-279. The reference to Reish Lakish’s death makes clear that these stories are meant to be heard along with the other Reish Lakish/Rabbi Yochanan stories (Bava Metzia 84a). After an interaction in the Jordan River, the bandit Reish Lakish committed to devoting his energies to Torah and married Rabbi Yochanan’s sister. Rabbi Yochanan taught him Tanach, Mishnah and turned him into a great man. (Other sources, and some language in Bava Metzia, indicate that prior to this Reish Lakish had been a Torah scholar who studied from others. See Tosafot d.h. אי הדרת בך ad loc.) Reish Lakish and his teacher Rabbi Yochanan frequently argued in Torah matters, and when they argued about the completion of metal vessels, Rabbi Yochanan said, “A bandit knows about his banditry.” Reish Lakish took offense, and said, “What benefit did you provide me? There, they call me leader [of bandits] and here they call me leader [perhaps rabbi, or perhaps of bandits].” Rabbi Yochanan was offended, and Reish Lakish took ill. The aforementioned wife pled on Reish Lakish’s behalf, for the sake of her children, and for her own sake. Rabbi Yochanan, citing the beginning and end of Yirmiyahu (49:11), promised that he (or perhaps Hashem) would care for them, something that seems relevant in our sugya.

After Reish Lakish’s death, Rabbi Yochanan was sorely pained. The Sages attempted to send Rabbi Eleazar b. Pedat, whose statements were sharp, to learn with him. However, each time Rabbi Yochanan said something, rather than arguing with him (as Reish Lakish did), Rabbi Eleazar cited a supporting brayta. Rabbi Yochanan had liked the challenges, by which halacha had become broadened. Disconsolate, Rabbi Yochanan lost his sanity and the Sages prayed for him and he died. In this context, I think the child’s intelligence, challenges and chutzpah (and indeed stating a lack of need for Rabbi Yochanan) echoed that of Resh Lakish, and was what drew Rabbi Yochanan to him.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.