Editor’s note: Dr. Mandell Isaac Ganchrow, Menachem Mendel Yitzchak, was niftar February 15, the 14th of Adar I, Purim Katan at the age of 85. His life led him from humble beginnings in Brooklyn to the line of fire in Vietnam, the halls of Congress and the White House and the presidency of the Orthodox Union. He was a giant in Jewish communal life and changed the pro-Israel political landscape for generations to come. The stories of his accomplishments were too vast to cover at the levaya, and numerous stories continued to emerge during the shiva week. Below is one of the hespedim given by his daughter.

Who was Mendy Ganchrow? If I had hours I could not even begin to come close in describing the leader, the visionary, the sheer life force that was my father. My dad graduated from Yeshiva University, where he was known as “The Governor” for his involvement in student politics. He went on to Chicago Medical School, and on summer break he met the beautiful Sheila Weinreb at the Pineview Hotel, where it was love at first sight for him. When he graduated medical school and my mom graduated Stern College, they married, preceded by the passing of my grandfather, who never got to walk my father, his son, down the aisle.

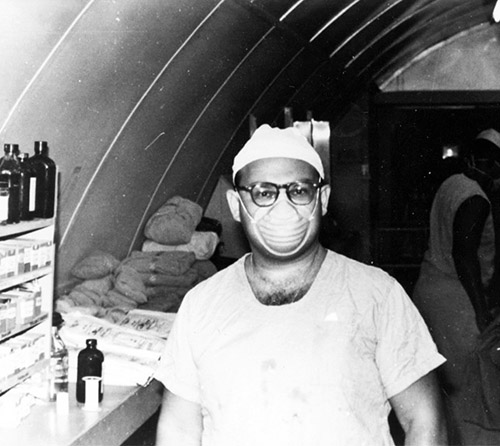

In 1968, when I was four years old, my father was drafted to Vietnam. My mother and I moved in with my grandparents for what was a tortuously long year. He served as a MASH surgeon, the frontline mobile hospital identical to the conditions made famous by the iconic show. My father never compromised his principles, eating only kosher and keeping Shabbos and Yom Tov as best as was allowed by wartime. My father took it upon himself to fill in as the Jewish chaplain, leading Shabbos and High Holiday davening. In his autobiography, “Journey Through the Minefields, from Vietnam to Washington, an Orthodox Surgeon’s Odyssey,” he describes a Seder he led in Vietnam for 400 non-observant soldiers. As they were halfway through, a loud whoosh could be heard, the unmistakable sound of incoming enemy rocket fire. Seconds later Vietcong missiles had impacted the base 500-1000 yards from where they were sitting. He writes that he could feel the spiritual uplift the Seder had been providing to the men, and his neshoma rebelled at the prospect of halting the Seder. In a split-second decision, and amidst the bedlam, he jumped on a table and shouted “Men, I give you my word as the ranking officer, that God will allow no harm to befall you if you perform the mitzvah of continuing the Seder.” It became instantly quiet, and the Seder was completed in almost surreal tranquility. And as it was finishing, everyone, with tears running down their faces, sang “L’Shana HaBa B’Yerushalayim” as if to affirm their faith in the God of Israel to protect them in the deadly jungles of Vietnam. He finishes his story by saying that looking back on his decision, he realized it was neither wise nor morally correct, and he probably could have been court martialed had there been any injuries, but it was quintessential Mendy Ganchrow, always trying to bring the joys of Torah and Yiddishkeit to those around him.

With the rank of major, my father made it out alive, and we then moved to Grand Rapids, Michigan, for a one year colorectal surgical fellowship. We were the only Jews in Grand Rapids, evidenced by our neighbors asking very innocently where our horns were. My parents moved mountains to get kosher food and to find a mohel when my brother Ari was born. My father had such pride in being an Orthodox Jew. When we built a sukkah, and the cars lined up to take pictures of something they had never seen before, he loved explaining the origins of the holiday and answer any questions bystanders had.

We next moved to Monsey where my brother Elli was born. My father became president of Community Synagogue of Monsey, with Rabbi Moshe Tendler, zt”l, as our rav. He also served as president of our local yeshiva, HIROC (predecessor to ASHAR), and grew a very thriving surgical practice. But his staunch Zionism yearned to be fulfilled and propelled him to form the Hudson Valley Political Action Committee, which he singlehandedly turned into the largest local Pro-Israel PAC in the country. He raised millions of dollars for pro-Israel candidates. Routinely, congressmen and senators would be in and out of our home in Monsey for meetings, or to speak at a fundraiser that my father had organized. I remember the surgical staff at Good Samaritan Hospital, where my father was affiliated, telling me that they had gotten used to chiefs of staff from the Hill or even the White House calling in to the operating room and insisting that someone break in to my father’s surgery so they could get his opinion and consent on an upcoming bill or vote that would affect the state of Israel. He wore his yarmulke proudly in the halls of Congress, Senate and the White House as well as when he met kings and sheiks. He donned it when he met with President Reagan to try to dissuade him from selling AWACs to Saudi Arabia, always affirming his pride at being an American patriot who had served his country as well as a proud Jew.

At 57, my father, fearing he would die at a premature age as his father had, retired from his practice and became the first full time lay president the OU had in its 96-year history. My father had more vision and ideas than anyone I had ever met. He was whip smart, insightful and never backed down or compromised when a Jewish principle was on the line. He grew the OU to unprecedented heights in programming and kashrut. He opened offices in Los Angeles, founded the OU Center in Israel and created a political arm in Washington. In 1999 Forward magazine listed him as No. 2 on their Most Prominent Jewish Leaders list. We are still hunting down No. 1. For 21 years my dad took it upon himself to teach a weekly shiur to six to eight non-observant doctors. He took them to Israel on five separate occasions, each time combining the trip with an impactful chesed component. For my father, the notion of tzedaka was non-negotiable. To this day when any member of that group sees my mother they refer to her as Rebbetzin. He continued this learning later in life when he joined Partners in Torah and studied weekly with a non-affiliated gentleman in Las Vegas. He also created an anthology of divrei Torah for sheva brachot, bar and bat mitzvah and bris milah so the lay person would have a resource for words of Torah. He coordinated the writings of 70 rabbis with all the proceeds going to NCSY. When have you ever heard of 70 rabbis agreeing on anything?

He authored his autobiography as a legacy to his children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren. I started re-rereading sections of it last night and I highly recommend it. It is a phenomenal story of a phenomenal man. My father viewed things through the lens of right and wrong, halachic or non-halachic. Even when he disagreed with you he did it with a twinkle in his eye. In my father’s world, you don’t come late to shul, you dress appropriately and you always carry yourself with honesty and morality striving to create a Kiddush Hashem. Which is why my father, upon returning from one of his many trips to Hong Kong, was the only passenger out of 450 to stand at the “items to declare” line. Even the customs official gave my father a wink and a nod trying to get him to write down that he had merely purchased a few t-shirts while abroad. My father, however, insisted on showing receipts and paying the full tax for the shirts and suits he had purchased. I am who I am because of my father. My family is who they are because of him. He is constantly in my ear reinforcing the notions of right and wrong and toeing the highest moral ground.

We wanted him for longer, but for him, every grandchild was a slice of heaven. Zach and Alex, Jake, Carlie and Jordan. Tommi, Jack and Becky, Jonah and Zahava, Matthew, Rachee, Hannah, Leah and Dovi, you all were the jewels in his crown. He loved to give you your own individual dvar Torah on Fridays, sing with you at the Pesach Seder or learn a sefer with you. He beamed with pride at every accomplishment. To have all his children and grandchildren Shomrei Torah and mitzvot was an affirmation of his life and his commitments. Adam, Henry and Raizy—three great-grandchildren—were the icing on the cake. He could never believe his luck living long enough to see a fourth generation. One of my children sent me a running list of both the funny things we loved about him, as well as

the serious things. The serious list included: Never wavered in belief in Hashem, fought through tough times, went out and did what he believed in, never took no for an answer, treated grandma like a princess. Many people texted and wrote beautiful notes following my dad’s passing. I would like to read one that for me hit the nail on the head as to who my dad was. “It was nothing that he ever said or did but I always felt small in your father’s presence. He was such a remarkable, well rounded and smart guy. He always was so sure of himself and spoke with such authority because of his experiences and wisdom. It was obvious how much he loved your mother, his children, but even more so his grandchildren. He was so lucky to see great-grandchildren. He leaves behind such a legacy. He was a giant of a man, and I was glad to be in his neighborhood for the last 40 years.”

It is the end of a beautiful, almost 60-year love story with my parents. My father was fiercely protective of my mother. They were symbiotic, traveled and lived life beautifully. And when my father’s health failed, mom, you took care of him with dignity and love that took my breath away, refusing an aide, insisting on being his sole support. When my father was admitted to the hospital almost three weeks ago, he was somewhat lucid and turned to my mother and in a barely audible voice said, “you are so beautiful,” and then he puckered up his lips to give her a kiss.

I want to conclude with a poem that my father sent my mother October 10, 1968, while he was in Vietnam.

I miss my Sheila more than ever

Our separation seems like 100 years

Each day is an experience of torture

To fight back the hidden tears

The fairness of this war has escaped me

I would not mind serving for a just cause

But I’d much rather be frolicking with my daughter playfully

Than operate on young Americans who are simply listed as a battle loss

This war has no end in sight

Only my constant thoughts of my wife

Help me ease the spectacle of the surrounding blight

And make my spirit come to life

She is the essence of my whole existence

Without her I would be lost

Her daily letters and tapes are the only matters of significance

That keeps me going in this unreal world

That is only measured in military cost

As I sat with my father I promised him that we would take care of you, Mommy, as we knew he would do if he was here. We will never break that pledge. Daddy, I love you, I always will. There will never be another like you.

Malkie Ratzker is the oldest of Mendy and Sheila Ganchrow’s three children. She is married to Paul Ratzker and has four children and two in-law children: Zach and Alex, Jake, Carlie and Jordan, Tommi. She has two grandsons, Adam and Henry. She lives in Livingston New Jersey, and is the coordinator of loan services for the Hebrew Free Loan of New Jersey, a job that helps members of the Jewish community in a time of need, and one she knows her father is proud of.