Carl Sagan fans old and new have been gazing at their televisions in awe as host Dr. Neil Degrasse Tyson’s resurrection of the science epic Cosmos takes them on a journey from the Big Bang, to microscopic one-celled organisms, to the ascent of man, to beyond the stars and planets.

The return of Cosmos—which launched in March and runs for 13 episodes on the Fox network, ending June 2—provides an opportune time to remember Sagan, the show’s Jewish creator.

An American astronomer, astrophysicist, cosmologist and author, Sagan was born to Reform Jews. According to science writer William Poundstone, author of Carl Sagan: A Life in the Cosmos, Sagan’s family celebrated the High Holidays and his parents made sure Carl knew the Jewish traditions.

“Both of his parents instilled in him this drive to get ahead in America, and that is something he kept all his life,” Poundstone explained. “It may have been one factor in this idea that he not only wanted to be a successful astronomer, but [also] to write books, to become a celebrity and an entrepreneur. His mother particularly instilled that in him.”

Born in Brooklyn to Samuel Sagan, an immigrant garment worker from Russia, and Rachel Molly Gruber, a housewife from New York, Carl was named in honor of Rachel’s biological mother Chaiya Clara. Both Carl and his sister say their father was not particularly religious, but their mother believed in God, was active in her synagogue, and served only kosher meat.

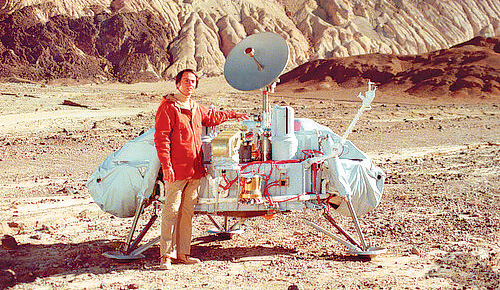

From an early age, Sagan was seized with the mission of searching for life on other worlds, a quest that would dominate his entire professional career. Poundstone recounts how this quest continuously drove Sagan, from his adolescent chemistry-set accidents, to his colorful academic career, to his professional work on the Viking and Voyager NASA missions, nuclear disarmament, Cosmos and Robert Zemeckis’s film Contact (starring Jodi Foster).

In 1986, the World Jewish Congress (WJC) presented Sagan with the Nahum Goldmann Medal, according to WJC North American press officer Eve Kessler. The medal is awarded to distinguished individuals for their contributions to universal humanitarian causes and actions benefiting the Jewish people. At that time, Sagan gave an address titled “The Final Solution of the Human Problem: Adolf Hitler and Nuclear War.”

“If the United States and the Soviet Union permit a nuclear war to break out, they would have retroactively lost the Second World War and made that sacrifice meaningless,” Sagan said after accepting the Goldmann medal. “If we take seriously our obligation to the tens of millions who perished in World War II, we must rid the planet of the blight of nuclear weapons.”

Also in 1986, Sagan received the Shalom Center’s first Brit HaDorot (Covenant of the Generations) Peace Award. Shared with Boston’s Jewish Coalition for a Peaceful World, the award was presented to Jews who work to prevent a nuclear Holocaust.

“We had relatives who were caught up in the Holocaust,” Sagan wrote. “Hitler was not a popular fellow in our household. On the other hand, I was fairly insulated from the horrors of the war.”

In his 1996 book The Demon-Haunted World, Sagan included his memories of this conflicted period when his family dealt with the realities of the war in Europe, but tried to prevent it from undermining his optimistic spirit. “Carl fulfilled his mother’s unfulfilled dreams,” said Poundstone.

Sagan spent most of his career as a professor of astronomy at Cornell University, where he directed the Laboratory for Planetary Studies. He published more than 600 scientific papers and articles and was the author, co-author or editor of more than 20 books. He advocated for scientific skeptical inquiry and promoted the search for extraterrestrial intelligence. But it was perhaps Sagan’s personality—not just his scientific credentials—that popularized Cosmos on the PBS television network.

“One of the reasons the original Cosmos series worked was Sagan was one of the few scientists who could wear jeans and a turtle neck and look comfortable,” Poundstone said. “He did have this vibe as someone who was cool and a member of the youth culture. That was a big part of the show’s appeal.”

Cornell University’s press release at the time of Sagan’s death called him the world’s greatest popularizer of science, as he reached millions of people through newspapers, magazines and television broadcasts. Cosmos—seen by more than 500 million people in 60 countries—became the most watched series in public-television history. The accompanying book, Cosmos (1980), was on The New York Times bestseller list for 70 weeks and was the best-selling science book ever published in English.

“Carl was a candle in the dark,” said Yervant Terzian, chairman of Cornell’s astronomy department. “He was the best science educator in the world this century. He touched hundreds of millions of people and inspired young generations to pursue the sciences.”

Sagan predicted that the surface of Venus was 900 degrees Fahrenheit, a finding confirmed by the Mariner 2 robotic space probe. “He was the architect of the greenhouse effect model of Venus’s atmosphere,” explained Poundstone. “Sagan’s model was a radical thing at the time but it was dramatically confirmed by the first NASA space probe. It was an incredible achievement. Sagan probably couldn’t have dreamed at the time that the greenhouse effect would be important in the current debate we’re having about whether human-produced carbon dioxide is changing our climate. His work was important to that.”

Promoted as a program that shows how matter, over billions of years, transforms into consciousness, the past and present versions of Cosmos speak to the joy one can find in nature, science and perhaps—as Sagan believed—the search for intelligent life in space.

Sagan was enthusiastic about sending messages to possible extraterrestrials. The Pioneer Plaques were a pair of gold anodized aluminum plaques placed on board the 1972 Pioneer 10 and 1973 Pioneer 11 NASA space probes, featuring a pictorial message in case either was intercepted by extraterrestrial life. The plaques show the nude figures of a human male and female along with several symbols designed to provide information about the origin of the spacecraft.

The Voyager Golden Record, a much more complex and detailed message using state-of-the-art media, was attached to the Voyager spacecraft launched in 1977.

“The Voyager Golden Record is often credited with spurring the degree of interest we have in world music,” Poundstone said. “They compiled this wonderful sampler of all the world’s musical traditions, which was something you didn’t get so much then but you do now.”

Poundstone identifies three elements that define Sagan’s legacy.

“He was a great, poetic writer and he was able to communicate that on screen,” he said. “Second, he tends to be underrated as a scientist, but he did incredible things including the greenhouse effect on Venus and a lot of work on Mars. He was the first to show that the dark areas were high mountains and not low seas. Third, he was a great advocate of the skeptic movement, the idea that you have to have evidence for a claim.”

By Robert Gluck/JNS.org