This year, on Isru Chag HaPesach, we commemorated my mother’s 10th yahrzeit. In truth, though, we lost my mother many years before April 2009. For several years my mother suffered from Alzheimer’s, perhaps one of the cruelest diseases of all, and ultimately had a stroke, which left her in a non-communicative state for four long years. Three generations of family members visited her regularly, sang to her, talked to her and held her hand, but we will never know if she was in any way aware of our presence. I do know, however, that it would be a terrible injustice to her if we did not document the brilliance of my mother and the extraordinary person she was. It is difficult to conjure up the image of the woman who raised us, who served as president of every organization she joined, who successfully tackled each Sunday New York Times crossword puzzle, who earned the respect of everyone she met and who served as the cornerstone of our extended family for decades. But while fate at first gradually and then cataclysmically robbed her of her abilities, it would be unfair for us to deny her the legacy she so deserves. It is an awesome undertaking to try to describe the meaning of someone else’s life, even if that person was your own mother. There is no way I could possibly guess at her innermost thoughts. But the impression she created was consistent throughout the years of her life, and I would be content to be able to convey just that.

My mother was born Grace Leonore Lesser, Gittel Leah, the daughter of Alfred Lesser and Martha Spiegel Lesser, in March of 1923, and was raised in the Bronx. She was a second-generation American on both sides. My mother was not brought up in a religious home. My grandmother lit Shabbat candles and kept kosher, but Shabbat was a day of trips to my mother’s large extended family of aunts, uncles and cousins, of movies and other everyday activities. My mother attended all-girls Walton High School, was a member of Phi Beta Kappa at Hunter College for Women and later studied at the New School, ultimately attaining a master’s degree in econometrics. One of her first jobs was at Columbia University, where she worked on the Manhattan Project, for which she ultimately received a letter of commendation from President Truman for her part in America’s wartime efforts.

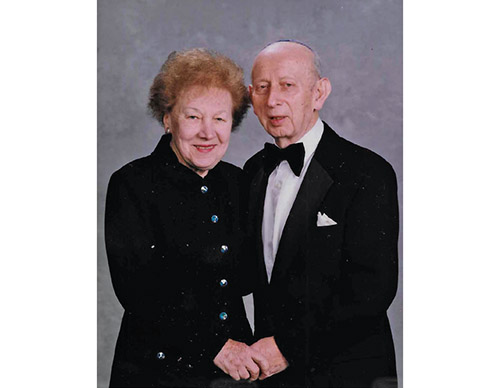

My mother met my father, Julius Rosenzweig, at a dance for Jewish singles in September of 1948. The dance was held during Aseret Yemei Teshuva, the days between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, and my father remembered hesitating before attending such a secular event during this solemn time of the year. Fortunately, he overcame his reservations. He asked my mom for her phone number but didn’t write it down. My mother, not yet knowing my father’s uncanny memory for numbers, never expected to hear from him. The rest is history. Her story became so inextricably intertwined with my father’s that their tales must be told the way they lived their lives: as one.

My parents’ relationship encompassed several leaps of faith on my mother’s part.

My father had left Germany in June of 1939 and was the sole survivor of his immediate family. There were no parents or siblings to welcome my mother into the Rosenzweig family. There was no opportunity to observe my father in the context of those significant family relationships that reveal so much about an individual. My father was, however, blessed with two maternal uncles and aunts and their children who embraced him and served in loco parentis as my mother and father formalized their relationship. It was only at the shiva for my father that a second cousin shared with us the story of her family’s “special” set of dishes. Apparently her grandparents, my father’s aunt and uncle, upon my parents’ engagement, assumed the responsibility of hosting the traditional dinner with their nephew’s future in-laws. To make a proper impression, they bought a set of dishes for the occasion. Those dishes remain in their family to this day, and every time their children and grandchildren use them, they reminisce about their origins. The circumstances of my parents’ engagement have become a treasured part of their family lore. I don’t know if my mother ever knew the story behind those dishes, but I’d like to imagine that the measure of love for my father that moved his aunt and uncle to undertake such an expense on his behalf was evident to her and, in her mind, helped compensate for those primary relationships he had lost.

Another leap my mother made was her willingness to commit to a life of shemirat mitzvot. In some ways, this entailed a dramatic change of lifestyle for my mother, but in others it simply involved taking her innate kindness and empathy for others and raising these traits to an elevated level of observance. We often speak of mitzvot bein adam laMakom and mitzvot bein adam lechavero, commandments that involve the relationship between man and God and those between man and his fellow man. Throughout her life, my mother was a role model for the latter and this manifested itself in countless ways. She was not a trailblazer. My mother was a well-educated and accomplished woman. In keeping with the social mores of her generation, she left her career behind and dedicated her talents and abilities to raising her family and to enabling my father to fulfill his responsibilities as the family breadwinner. She did homework with us every night and drilled us before each test we took. There was a fresh, hot dinner waiting for us after school each evening. She was protective of my father upon his return home from work, and we knew that my parents’ dinner time together was sacrosanct and never to be disturbed. The housework was exclusively her domain.

A major part of my parents’ life-altering journey took place after they moved to Woodmere from Parkchester in 1959. Spurred largely by their desire to raise their children in a more Jewish environment, my parents bought a home in Woodmere when it was still pioneer territory for Orthodox Jews. My parents’ intention was to send my siblings and me to the local public school, but at the advice of the founding members of the Young Israel of Woodmere they decided that yeshiva was the way to go. As my siblings and I attended HILI in nearby Far Rockaway and received our Jewish education, so our parents received theirs. As we learned the intricacies of halacha, so did they. And their willingness to accept all that we brought home and shared and to incorporate these teachings into our family’s way of life was reflective of their ever-growing commitment to Yahadut and both the familial and communal responsibilities that this commitment entailed.

It was in Woodmere that Grace Rosenzweig truly came unto her own. The urban woman metamorphosed into a suburban legend. She learned to drive and became a prime patron of Central Avenue’s shops as well as a modern-day carpooling mom. She became an active member of the Young Israel’s sisterhood, and after holding multiple positions and chairing countless theater parties and fundraisers she became sisterhood president. Her evolution in Mizrachi and later AMIT Women followed suit, as did her involvement in the PTA at HILI. My mother’s intelligence, organizational skills and sense of fairness propelled her, time and again, into positions of leadership and facilitated her involvement with dozens of women of all ages, whose respect and admiration she never failed to win. As president of the HILI PTA, she served as the school’s conscience. The successful protest she mounted against the school’s decision to refuse readmission to at least one family because of their inability to pay tuition is reflective of the sense of fairness and compassion that drove her throughout her life.

My mother was more affectionately demonstrative than my father. But the care my father took of my mother throughout her illness was a beautiful testament to his love for her and his desire to allow her to maintain a reasonable quality of life. When my mother had the stroke that robbed her of all of her abilities, it was my father who made the decisions regarding my mother’s care. The doctors advised my father to let my mother go. Time and again he refused. He asked that they do whatever they could to prolong her life. Late one night, as I sat with one of the doctors, he asked me why my father refused to allow her to die. I told him about my father’s history and the family he had lost in the Holocaust. I explained that he had lived his entire adult life, blaming himself for not having been able to save his mother and sister from their fate, and that there was no way he could possibly live knowing he had allowed yet another beloved family member to die on his watch. The doctor understood this. It seemed to make some sense of the incomprehensible stance my father had taken. But in all honesty, I don’t really know if this was the explanation. Every day for four long years he visited her at the hospital or nursing home after work or after Shabbat. He continued to make medical decisions that he hoped would prolong her life, though some of them were quite drastic. There could have been no greater demonstration of love and affection than what he showed my mother during that most difficult and lonely time in his life.

To my mother, there was no greater value than that placed on family. She was the most giving of women, a true partner to my father in all of his accomplishments and a source of an incredible work ethic and sense of communal responsibility that she instilled in each of her children and that has been passed on to yet the next generation. Her shem tov was founded on outstanding ability coupled with humility and a profound sense of fairness and compassion for others, on a commitment to getting the job done no matter the personal cost, and on a sense of loyalty to family and friends that was sorely missed when she was no longer able to fill that role. I fear that her long, sad end detracted from the everlasting legacy she so deserved. She was a true heroine, a woman of courage. May her memory be a blessing for all who were privileged to know her.

By Barbara Rotenberg

�