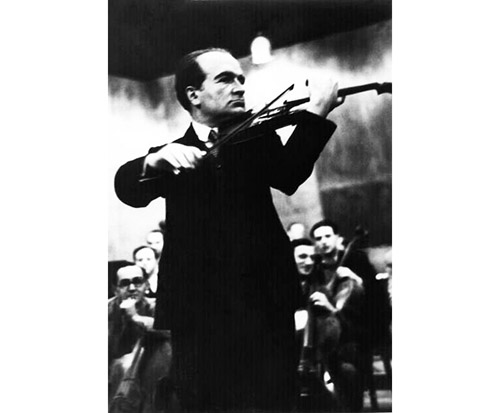

On December 26, 1936, Arturo Toscanini, indisputably the greatest maestro of that time, working under less than ideal conditions and in an area under tight British control, conducted a mostly pan-European group of musicians in Tel Aviv. Toscanini charged neither a fee nor expenses for his services. It was not the last time he would honor this fledgling group of refugees. It has been 82 years since that inaugural concert, and as defiant and courageous an anti-Fascist as Toscanini was, he is not the main protagonist of this story. Bronislaw Huberman is.

Although Spielberg’s work brought Oskar Schindler’s heroism to international audiences, relatively few students of the Holocaust have become acquainted with the story of an equally heroic man, a Schindler of music—Bronislaw Huberman, who single handedly darted in and out of Germany and Nazi- and Fascist-sympathetic Europe to rescue virtuosi and their families. Huberman faced formidable obstacles, not the least of which was deciding whom to select for the “orchestra of exiles” he meticulously planned. He knew that in selecting some musicians over others, he may well have sealed the fates of those he rejected—and their families.

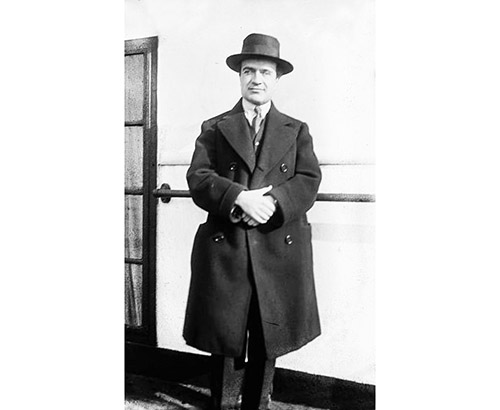

Huberman, born in 1882, came from a poor family in Poland. His father, Jacob, left his job as a clerk to accompany his son first to Warsaw for violin lessons and then to Berlin to study with Joseph Joachim, the consummate violinist of the time. Joachim was a close friend and interpreter of Brahms, who himself had seen the teenager perform in 1896 in Vienna. The 14-year-old’s rendition of Brahms’ Violin Concerto had so moved the composer that after the performance, he hugged the prodigy, praised him, and predicted his greatness.

Given the many invitations from abroad that Huberman received, his father arranged a global tour. The violinist was a sensation, lauded in 1896 by The New York Times. Thus was launched a brilliant international concert career, one that took quite a bewildering turn.

After his father’s untimely death in 1902, and the Great War, which had left an indelible mark on Huberman’s thinking, the boy wonder did something quite unprecedented in the world of music. At the peak of his success, acutely aware of politics and humanism, he suspended his concerts and went to study for two years at the Sorbonne. There Huberman became an advocate of Pan-Europeanism, like many intellectuals of the time, including Albert Einstein. He joined the movement for peace that was brewing in Europe. In taking this “recess,” Huberman, unlike most musical geniuses, interrupted a flourishing concert circuit.

The Nazis’ rise to power in 1933 and the ensuing Nuremberg laws disabused Huberman of his hope that peace in Europe would come to fruition. Jewish musicians were no longer permitted to play in German orchestras and Jewish performers of all persuasions were out of work. The renowned German Berlin Philharmonic conductor Wilhelm Furtwangler had received from Goebbels a rather tenuous concession that Jewish musicians in the Philharmonic would be able to perform in the orchestra despite the anti-Jewish decrees. Furtwangler, a non-Jew, had himself wrestled with the idea of leaving Germany, but ultimately remained to conduct the Philharmonic throughout the Second World War.

As for Huberman, he had by no means been a Zionist. His hopes had been for a united, peace-driven Europe. Yet, given growing anti-Semitism and a looming specter of Nazi occupation elsewhere, he not only realized that there was no future for Jews in Germany, but that the only hope for Jewish musicians who were targeted, and would in the future be targeted, was in Palestine.

Securing papers for these musicians was a far more difficult task. In addition to those musicians who auditioned for Huberman, there were written requests from others. Huberman had to personally appeal on their behalf to authorities in England and elsewhere for the documents permitting them to emigrate.

Arturo Toscanini’s experiences in the music world paralleled those of Huberman. The latter’s cognizance of the Nazi threat had catalyzed his rescue mission, but both men refused offers to work in an environment of harassment, persecution and death. Toscanini had already fled Italy, after the authorities there had twice confiscated his passport. Clearly opposed to the Nazi measures to ostracize Jews, Toscanini empathized with the plight of the musical virtuosi who had been fired. Huberman approached Toscanini to conduct the first concert of the Palestine Symphony Orchestra. The maestro agreed to do so, and subsequently conducted additional performances.

Despite harsh physical and environmental conditions, political struggles to accommodate a growing post-Holocaust refugee population, and war, the orchestra flourished. Other esteemed artists, such as Leonard Bernstein, came to conduct it during those birth-pang years. The orchestra struggled, but in time, and with additional resources, it was transformed into the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra.

As for Huberman, the years and the hardships took a toll on his health and his relationships. His first marriage, to actress and singer Elsa Galafres, which produced his son Johannes, failed. He later found love and companionship with Ida Ibbeken, who had nursed him during a major illness. She became his companion and devoted assistant, often traveling with him on tours, fundraising trips, auditions and rescue missions.

Huberman survived a 1937 plane crash near Sumatra, and after a period of rehabilitation went on to tour and play benefits for various causes worldwide. After the war, he continued his performances but spent six months in Italy restoring his health. On June 16, 1947, he passed quietly, with Ibbeken at his side.

Although there is no exact count of how many people were saved through the efforts of “Music’s Schindler,” the likelihood is that Huberman’s interventions saved close to one thousand lives, not counting the generations of musicians’ families who owe their existence to his bravery, persistence and, of course, brilliant artistry.

Josh Aronson’s excellent documentary, “Orchestra of Exiles,” which aired on PBS in April 2013, brought Huberman’s story to broader audiences. Nevertheless, to date, many still do not know how the melding of Huberman’s talent, perseverance and outright “chutzpah” resulted in the rescue of so many artists, not to mention the scores of their descendants who survived, despite the Nazis’ attempts to silence them, and their music.

By Rachel Kovacs

Rachel Kovacs is an adjunct associate professor at City University of New York. Please note this article is proprietary/copyright protected.