Part III

(continued from last week)

In the office of Philipp Brothers where I worked for 36 years, starting right out of college in 1949, until I took early retirement in 1985, unfortunately, we had some executives who objected to my department “becoming a yeshiva.” He/they were referring to the fact that a large proportion of the staff were young Orthodox men. Since one of my responsibilities in the department was to give the initial interview to new applicants, I also felt it was my responsibility to make sure that it remained my responsibility to give these young applicants an opportunity to work in surroundings where they would have no difficulty with Friday afternoon, Shabbat and Yom Tov, have a good and secure income and be able to start a family. I was afraid that if I would let the young men wear a kippah in the office I would be held responsible, and then others would handle the interviews, with the resulting consequences.

Therefore, whenever I interviewed a young man, and during the interview he wore a kippah, I would explain to him what the company policy was. I never asked anyone to take the kippah off but suggested that he consult with his rabbi. I never had a problem, since the new employee would invariably report to work and not wear a kippah in the office. During lunch while eating or learning they wore a kippah without any problem. Consequently, I was able for those many years hire who I wanted and thereby gave many a young person a good start.

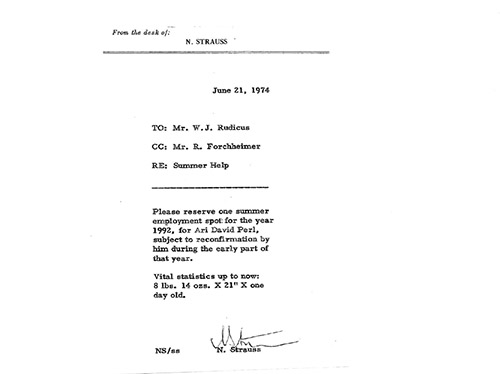

Now that I have given the reader the practical side of wearing a kippah, I took some time to read up on various articles that my grandson Rabbi Ari Perl was able to obtain for me.

My first reading was a presentation given by Aminadav Grossman to the Department of History at Columbia University. I assume it was his doctorate theses. It is titled “The Story of the Yarmulke from 1945 to 1975.”

(Just as an aside, when Rabbi Jonathan Knapp, my wife’s son, saw what I was reading, he commented that he had Aminadav in his school, and that Aminadav had been a brilliant student.)

The first comment in the early pages of his presentation was that in the early to mid-20th century, the yarmulke was considered by Orthodox Jews as an “indoor garment.” But, when after WWII Eastern European Jews arrived in the U.S., a more stringent religious lifestyle became evident. The Six Day War in Israel and the religious revival in the 1970s certainly had an impact on the popularity of the yarmulke.

Mr. Grossman cites many other opinions, some pro and some con, about wearing a kippah in public. Nevertheless, there remained areas in business where Jews could/would not wear a kippah without attracting unwanted attention such as in courtrooms, schools and offices. Rav Moshe Feinstein stated that “the potential loss of one’s livelihood overrides many positive Torah precepts and especially one like head covering that is only a ‘pious practice’ or a ‘good custom.’”

I did not know at the time I worked at Philipp Brothers Inc. what Rav Moshe Feinstein had stated, but had I known it, it would have meant moral support for my actions when interviewing applicants. Many years later the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission released guidelines in March 2014 for dress in the workplace, which would have made my job more difficult. But there were in the 20th century many other actions as an employer that in the 21st century would not be acceptable anymore. Since I was guilty in the 20th century, I must admit, but I make no apology since my actions, when viewed now in the 21st century as illegal, gave a great many young people a very much desired employment opportunity.

Rabbi Mordecai Breuer in his article “Modernity within Tradition, The Social History of Orthodox Jewry in Imperial Germany” also comments on the many customs of pre-WWI Jewry, such as ladies’ dresses, uncovered hair, shaking hands with the opposite sex that in later years was not acceptable anymore.

Dan Rabinowitz, an attorney practicing in Washington D.C, wrote an article titled “Yarmulke: A Historic Cover-Up?” published in “Hakirah” in 2007. He stated that when Rabbi David Tzvi Hoffmann (1843- 1921) was teaching in “the school in Frankfurt am Main, that was established by Rabbi Samson Rafael Hirsch, the students sat bareheaded for secular studies. Only during Judaic studies did they cover their head, and this was done under the direction of Rabbi Hirsch.” Rabbi Hirsch also complained to Rabbi Hoffmann during their first meeting for not taking off his hat since it showed a lack of proper respect.

It is my recollection when I attended the Rabbi Samson Rafael Hirsch Realschule in Frankfurt in the mid 1930s that what Rabbi Hoffmann describes is exactly what the situation was even then.

There are many other very interesting comments cited by Mr. Rabinowitz in which well-known and respected rabbis gave a lenient view of covering the head.

An article titled “Men’s Head Covering: The Metamorphosis of This Practice” by Eric Zimmer as part of Essays in Memory of Rabbi Dr. Leo Jung, titled “Reverence, Righteousness, and Rahamanut,” and edited by Rabbi Jacob J. Schacter, also has many opinions of well-known and respected German rabbis regarding head covering. It is of interest to note that Mr. Zimmer also quotes the above-mentioned Rabbi Hoffmann’s comment of what his experience was in Frankfurt in the Hirsch School.

In view of these comments I feel comfortable that my recollection of my years in Frankfurt is correct regarding the wearing of a head covering.

Norbert Strauss is a Teaneck resident and Englewood Hospital volunteer. He frequently speaks to groups to relay his family’s escape from Nazi Germany in 1941.