The most precious remnants of the Shoah are the living survivors whose strength and determination to rebuild lives are an enduring example through their families, writings and recordings.

Still, there are inanimate remnants of the story that can serve to illustrate and substantiate the things we have learned about this era. Here I present a few items from my collection. (Some 600 images of additional artifacts and descriptions concerning German and Polish Jewry can be seen on my website Virtualjewishmuseum.com.)

Jews had lived in Germanic lands since the Roman Empire. Despite repeated persecutions, they flourished. They were merchants, officials, doctors, even mint-masters and with the decline of Middle-Eastern communities, Germany became a major center of rabbinic scholarship. Figure 1 shows a coin minted in Wurzburg Germany in the early 1200s. We see clearly the name Yechiel in Hebrew letters. He must have been in charge of the mint. Above is a depiction of the medieval cathedral in the town.

Anti-Semitism was a fact of life in Europe, but it became much stronger after World War I. Joblessness and hyperinflation called for a scapegoat and Jews were an easy target. Law-abidance, army service, productivity—none of this could stop the barrage of anti-Semitic propaganda. In Figure 2 we see a lapel pin worn before elections. It asks: “National Freedom or Jewish Dictatorship?” The tall, hard-working German on the left with the glow of the sun behind him is trying to defend himself from the short bearded Jew with hands like paws, who raises his whip of oppression as he emerges from the devilish flames.

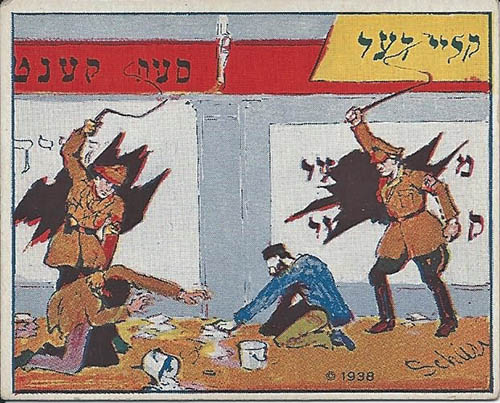

Once the Nazi party achieved power, they made laws that excluded Jews from society, taking away rights, citizenship, jobs and wealth. They moved on to destruction of property and bodily harm. They looted shops and made Jews scrub the streets in front of them. Figure 3 is a bubble-gum card from a set showing aspects of the World War. It portrays the physical abuse of Jewish Austrian citizens after Germany occupied Austria in 1938. The stores have Yiddish signs and the men on their knees are obviously Jewish.

The next step was to separate Jews from the rest of the population. In Western countries, Jews were relocated and “concentrated” in camps outside of towns. In the East, where the Jewish population was enormous, sections of cities were closed off from the world, and Jews were herded into them from their own homes. These ghettos were locked, guarded and provided little work or food and no health care. Starvation and disease took their toll. Figure 4 shows a ghetto coin from the Polish city of Lodz. Regular money was confiscated (so it couldn’t be used for escapes or bribes) and replaced with this aluminum token money.

Next, Jews were sent from camps and ghettos to killing centers. They were stuffed into railroad boxcars that had been used to ship cattle. Upon arrival, some were kept alive to perform slave labor, and got numbers tattooed on their arms. Many others were simply killed. Figure 5 shows a commemorative medal illustrating the heartbreaking scene of a mother and children about to board such a train.

Despite the overwhelming feeling of hostility and abandonment that Jews in Europe felt, there were some cases of local help and support. Decent Christian neighbors and even strangers who were outraged by the murderous policies of the Nazis undertook to feed, smuggle and hide Jews who were running for their lives. (The most famous instance of this was Anne Frank’s family, who were hidden for two years by employees before they were discovered.) When Yad Vashem was established, in the new State of Israel, one of their first projects was to identify and honor non-Jews who had risked their lives to save Jews. They were brought to Israel, honored as “Righteous Gentiles,” and given a medal that says: “A Symbol of Gratitude from the Jewish People” and has room to engrave the name of the recipient. Figure 6 shows such a medal that is engraved with the name of the Polish family that received it.

The events of 1938–1948 would be unbelievable were we not able to speak to those who lived through them: the unimaginable horrors of the Shoah followed by the fantasy-become-reality of a renewed Jewish homeland. We continue to live with the effects of both of these events. Figure 7 tries to sum them up in one medallic image. A mighty tree represents the Jewish people. It has been cut down by the Nazi axe, engraved with a swastika. Lightning from above strikes the axe and breaks it. And we see a young sapling growing from the trunk of the fallen tree. The Jewish people is seriously wounded, but survives—Am Yisrael Chai.

By Rabbi Binyamin Yablok

Rabbi Yablok speaks to schools and synagogues on a variety of Jewish topics, all illustrated with original artifacts. He can be reached at [email protected].