In parshat Mishpatim (Shemot 21:18-19), the Torah discusses two people fighting, and one strikes his fellow with a stone or fist, injuring him. He has to pay for the victim’s idleness (שִׁבְתּ֛וֹ יִתֵּ֖ן) as well as for healing him (וְרַפֹּ֥א יְרַפֵּֽא).

What do we do with the doubled language, “he shall surely heal him”? There’s a classic argument (Sanhedrin 90b) between Rabbi Akiva, who interprets doubled language (הִכָּרֵ֧ת ׀ תִּכָּרֵ֛ת) and Rabbi Yishmael who maintains the Torah employs human speech patterns, דִּבְּרָה תּוֹרָה כִּלְשׁוֹן בְּנֵי אָדָם. Are Rabbi Yishmael and Rabbi Akiva always consistent? As I’ve discussed previously, the Talmudic Narrator often invokes דִּבְּרָה תּוֹרָה to end derasha chains (X interprets this verse; Y derives the same law from here), sometimes inconsistently.

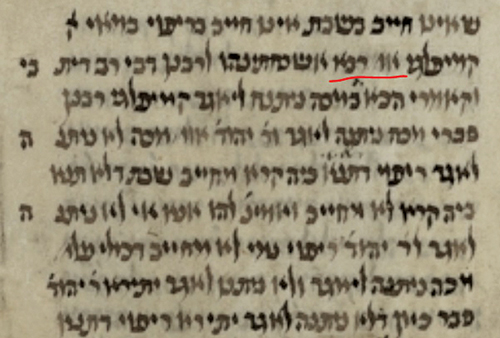

Our sugya (Bava Kamma 84-85) provides three interpretations from וְרַפֹּ֥א יְרַפֵּֽא. (A) Rav Pappa citing Rava, לִיתֵּן רְפוּאָה בִּמְקוֹם נֶזֶק, to pay for medical costs even when he also pays for damage. (B) Rabba (bar Nachmani) in conversation with the Sages of Rav’s academy, or alternatively1 Rava in conversation with the Sages of the study hall about the first Tanna in a Tosefta: if the injury resurfaces, he must repeatedly heal him. (C) The Talmudic Narrator, explaining how the other Tannaim in the Tosefta interpret the verse: they maintain like the Tanna of Rabbi Yishmael’s academy: that “reshut” is given to the doctor(s) to heal. Later, the Talmudic Narrator explains how one doubled language of וְרַפֹּ֥א יְרַפֵּֽא can teach A, B, and C, since other vocalizations or phrasings were possible. We seemingly rule like C.

I don’t know if Mechilta deRabbi Yishmael must be consistent, but there, וְרַפֹּ֥א יְרַפֵּֽא teaches B. Then, alternatively (ד”א), the Torah teaches derech eretz (ד”א), proper conduct, that רק שבתו יתן ורפא ירפא. I’d understand that to suggest that someone should take it easy, on bedrest, in order to properly heal. Then, this ד”א isn’t an interpretation of doubled language, but of the pasuk’s juxtaposition. However, our texts put that in parentheses and place C in brackets. Meanwhile, in Mechilta deRashbi, in which Rabbi Shimon ben Yochai interprets according to Rabbi Akiva’s school, we see both B and C2.

Permission or Empowerment?

Is interpretation C within the halachic or hashkafic realm? When Hashem gives “reshut” to doctors to heal, we might otherwise think that Hashem harms and so only Hashem should be allowed to heal. (See Rashi on 85a: ולא אמרינן רחמנא מחי ואיהו מסי.) Or, is it that Hashem empowers doctors to heal, and otherwise nothing the doctors do can help?

Bava Kamma isn’t the original context, since it is the Talmudic Narrator invoking an idea stated by Amoraim elsewhere. Perhaps the original context, Berachot 60a, can shed some light. A brayta describes a blessing said upon entry to a Roman bathhouse, which was dangerous. Abaye objects that one shouldn’t recite this blessing, because of not opening one’s mouth to the Satan to provoke him. Rav Acha describes a prayer upon exiting the bathhouse, thanking Hashem for saving him from the flame. Rabbi Abahu then acts in a certain way, and the Talmud says הַיְינוּ דְּרַב אַחָא. The next statement is attributed to Rav Acha in our printed texts and some manuscripts, דְּאָמַר רַב אַחָא, but this is an error due to dittography. Munich 95 and Oxford 366 correctly have this as a separate brayta, parallel to the preceding brayta about a bathhouse3.

The brayta gives a blessing for one who enters to have his blood let: “May it be Your will, Hashem Elokai, that this enterprise be for healing and that You should heal me. As You are a faithful God of healing and Your healing is truth. Because it is not the way of people to heal, but they have become accustomed.” Abaye again objects that one shouldn’t say this, because they taught in Rabbi Yishmael’s academy C: ״וְרַפֹּא יְרַפֵּא״ — מִכָּאן שֶׁנִּיתְּנָה רְשׁוּת לָרוֹפֵא לְרַפּאוֹת. Finally, Rav Acha (Rif and Rosh have “Rava”) gives a blessing on emerging from the bloodletter: בָּרוּךְ רוֹפֵא חִנָּם.

Rashi is consistent, and interprets לְפִי שֶׁאֵין דַּרְכָּן שֶׁל בְּנֵי אָדָם לְרַפּאוֹת אֶלָּא שֶׁנָּהֲגוּ to mean that they should not have gone to a doctor but rather to beseech mercy. (Indeed, the Oxford 366 manuscript has ורפואתך רפואה לפי שאין דרכן של בני אדם רשאין להתרפאת בכך אלא שנהגו; similarly Paris 671.) And this idea is what Abaye rejects. The Rif, Rosh and Rambam cite this blessing lehalacha, but heed Abaye’s objection and much of the middle. They replace it something akin to Rav Acha’s exit formulation, כי רופא חנם אתה.

However, another interpretation is hashkafic. Let’s assume רְשׁוּת means dominion, authority, and power. Similarly by כֵּיוָן שֶׁנִּיתַּן רְשׁוּת לַמַּשְׁחִית in Bava Kamma 60a. Then, רוֹפֵא נֶאֱמָן means that Hashem is a God of faithful healing, וּרְפוּאָתְךָ אֱמֶת means that unlike other cures, Hashem’s cure is true. Borrowing from Oxford 366, ורפואתך רפואה means that Hashem’s cure is indeed a cure. Then, “it is not the way of people to heal” means that it doesn’t work, but still, this is the fake effort that people go through. To this, Abaye objects that Hashem has invested power in physicians to heal, and that is the mechanism through which He operates.

Of course, modern medicine doesn’t often use bloodletting or leeches, except to treat particular ailments. It was popular alongside the now-discarded theory of the four humors (blood, phlegm, black bile, yellow bile) governing the health of the body. If so, perhaps the brayta’s hashkafic approach was correct, at least about bloodletting.

1 While the Vilna, Soncino, and Venice printings (and Bologna fragment) have Rabba, the Florence 8-9, Hamburg 165, Munich 95, Escorial, and Vatican 116 manuscripts all have Rava. The Sages of bei rav might mean the study hall (in Pumbedita, or Mechoza), or it might mean the academy of Rav, meaning Sura. Selecting the earlier Amora tilts towards Rav’s academy; selecting Rava tilts towards a study hall. For more on this ambiguity, see my earlier article (“Rabbanan Devei Rav”, September 15, 2021).

2 We probably shouldn’t amend our sugya to refer to Rabbi Shimon’s academy, despite Yoma 59a.

3 In Toledot Tannaim vaAmoraim, Rav Hyman grapples with the question of whether the well-established Israeli fourth-generation Amora, Rabbi Acha, interacts with Babylonian Amoraim. Our sugya seems like evidence of interaction with Abaye, but Rav Hyman argues, with solid reasoning, that this must be the Tanna, Rabbi Acha. However, manuscripts have Rav Acha, not Rabbi Acha, and manuscripts also make clear that Abaye argues with a brayta, not with Rav Acha.